Last Friday, I skipped lunch and went back to my Boston hotel room to watch Congressman Elijah Cummings’s funeral on TV.

Thirty-five years ago, when he was still a lawyer, we had a case together. I was representing a modular building company and he was representing one of the prominent African American churches in Baltimore, which had contracted with my client to buy and construct a building for Baltimore city primary school students.

Elijah and I met on the top floor of the church overlooking North Avenue where the ministers’ offices were located. He came over, shook my hand, and said, “I do a lot of criminal law and you know a lot more about business law than I do. Can we agree to work to make this fair for both sides?” I shook his hand and agreed that would be our objective.

The contract negotiations and construction took some time. As the building went up, there were adjustments to the plans and “change orders,” as there always are in construction cases, but we were candid with each other and each time we got it right.

Years later, I was at the Democratic convention in Boston and he saw me and came over and with a big smile he said: “Yeah! We learned to work well together didn’t we?” We both laughed.

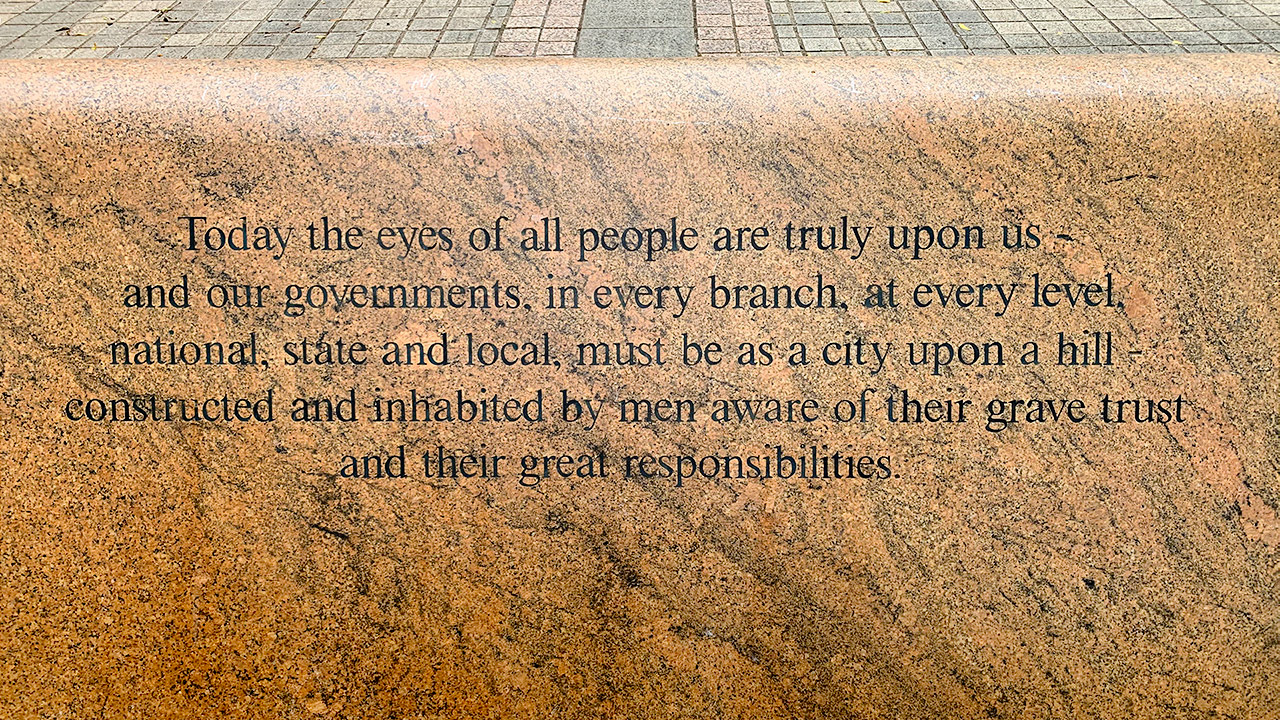

I grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and one of my favorite places is an old rusted fountain dedicated to John F. Kennedy. It no longer works but still has his quotes chiseled on its sides.

My hotel was in Harvard Square, so after the funeral I walk down to the fountain and read the quotes again:

“Today the eyes of all people are truly upon us — and our governments, in every branch, at every level, national, state, and local, must be as a city upon a hill — constructed and inhabited by men aware of their grave trust and their great responsibilities.”

Next to the forgotten monument was a sign that said: “No Skateboarding.”

No one was there except a skateboarder, practicing and re-practicing his art, and me.

It occurred to me that there are always laws which will be broken but we all, somehow, are subject to a deeper code. This was what Elijah understood.

Thousands of people, whether in the church or on TV, watched Elijah’s funeral. They watched and listened and were there because Elijah was an example of something we seem to not be able to forget.

Although in our daily lives and in our politics and governance it is sometimes lost, it is there in that handshake, that eye contact, that second thought that reminds us that it is as constant as gravity.

I saw Elijah on and off after that, in airports or at campaign events. He had become my Congressman. We would smile or wave. We were not friends, but we had once come to an understanding because he had offered up his vulnerability so that I could offer mine. And we could trust each other just long enough to do something right.