by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 17, 2025 | Featured, General, Humor, Law, Personal, Politics

When I started to practice law, Jimmy Carter was elected president. To avoid some unimaginable conflict of interest, he sold his family farm for peanuts. Since I retired from the practice of law 10 years ago, apparently the ethics have changed.

President Trump for his birthday last week gave himself a military parade, which which cost the American taxpayers approximately $25 million and tore up the streets of Washington.

Several news services have recently reported that since the early days of President Trump‘s reelection campaign he has made more than double his net worth, about $5.4 billion dollars.

In the past, I would’ve been horrified, but now my reaction is that it’s a shame I didn’t somehow make a bigger profit back when ethics prohibited me.

Back during those ethical times I would preach to the lawyers at my firm that the easiest way to check your professional ethics is to ask yourself if what you were about to do would be embarrassing if it would become a headline in the New York Times. If so, don’t do it.

President Trump has re-organized and turned upside down the professional ethics of the presidency and the ethics I was used to. Everything unethical or untrue that Trump has done now is routinely front page headlines on the New York Times, which nobody reads anymore.

I have gone back to thinking about how rich I would be if I’d taken on cases that I ultimately rejected long ago because of ethical concerns.

Consider the amount of money I could’ve made if I had taken that case long ago of two Hindu businessmen who came into the office and told me they wanted to incorporate (for personal liability reasons) an ongoing business that provided Hindu Americans a chance to bury their families in the Ganges River for about $5,000 per loved one.

They told me that the contract that they offered guaranteed that the loved ones ashes, with which they were entrusted, would be respectfully sent to the Ganges, a boat would be hired as well as a videographer to make a movie of the ceremony as the ashes were transported in a beautiful urn, and a man rowing the boat out in the Ganges would be filmed opening the container and emptying it so the ashes were visible as they were were gently poured into the river.

The $5,000 would be collected in exchange for the video of the ceremony.

I will admit I was intrigued by this novel, religious practice and I asked about the heavy cost of the procedure and the profit they were making per contract.

Without batting an eye both businessmen looked at me and said it was about 95% profit. I asked them how could they possibly make such a profit and they answered: “We send everyone the same video.”

If you’re using the same video and you are making a 95% profit you certainly don’t have to be greedy. You could include a beautiful hologram of the soul rising from the Ganges and fluttering off into reincarnation.

Also they completely missed the opportunity for relics, swag, and real cool T-shirts.

When you include the total Trump’s family and political friends have made in the “pay to play” access and favors, which have included the opportunity to show your personal love and respect by purchasing Trump bitcoin and Trump Bibles, and such gifts as an airplane from the government of Qatar, no wonder Trump wants a third term.

I was so stupid I refused to represent the two Hindu businessmen, even though they generously offered me a free burial in the Ganges.

I could also have befriended the President by referring him to another client who I rejected. For a while, “viatical contracts” were easy money. Several people had the idea at the same time. During the AIDS epidemic several entrepreneurs were going into hospitals or hospices and offering to buy life insurance policies at about 10% of their face value from those who would soon die. There’s nothing illegal about that, but for me it didn’t pass the smell test.

There is some justice in the world. Once effective HIV treatment became available, they were stuck continually paying for ongoing life insurance policies.

I suspect that the Trump family has already seen the future of medical profit as is evident from the appointment of Robert Kennedy, Jr. and the future of TMD (Trump Measles Deterrent). This is not a vaccine. it is free and called “The Trump Blessing,” which is administered over a Zoom call after you buy some of the remaining overstocked Bibles that will become collectors items soon.

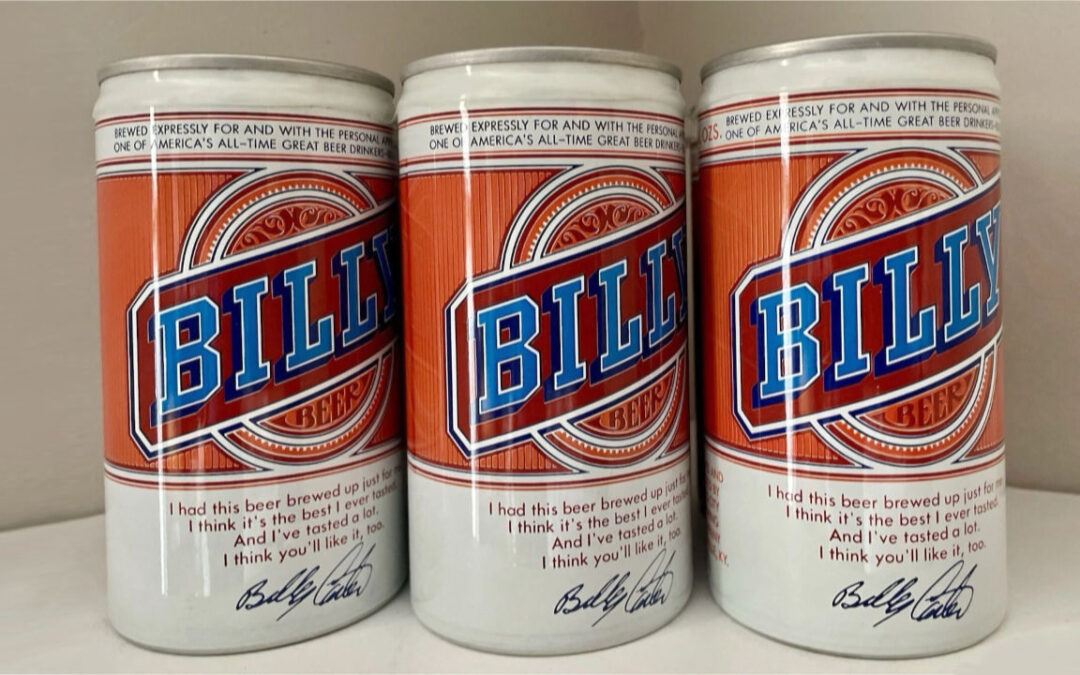

I think the only benefit Jimmy Carter received from his presidency was a gift given by his brother: a couple of cans of Billy Beer.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 16, 2025 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Politics, Travel

I’m not really worried about Trump taking over Harvard, so Susan and I are going to Paris this Saturday for a couple of weeks.

Why is everybody so upset? It seems like all the commentators have completely overlooked Trump’s leadership skills when he ran Trump University.

Trump has been very vocal about his business acumen and, by his own account, he ran the university brilliantly for the five years before its bankruptcy.

There was some unsubstantiated criticism about gold toilet seats, but he claimed he was always very hands-on and was good at keeping the overhead low.

For example, despite its name, Trump University was never an accredited university or college. It did not confer college credit, grant degrees, or grade its students.

Think about the savings on the cost of paper.

In contrast, the data from the 2023–24 academic year, 72% of Harvard University’s first-time, full-time undergraduates received financial aid. In the alternative, Trump University was apparently so popular, it never needed to offer scholarships. And Trump has already said that he wants to get rid of Harvard’s nonprofit status.

Really! So where is the art of the deal?

Harvard is not effectively selling its product! No. Harvard has been giving it away for free.

What is also great is that Trump has the experience to navigate these litigious times. In 2011, Trump University became the subject of an inquiry by the New York Attorney General’s office for illegal business practices, which resulted in a lawsuit filed in August, 2013. It was also the subject of two class actions in federal court. The lawsuits centered on allegations that Trump University defrauded its students by using misleading marketing practices and engaging in aggressive sales tactics.

Of course!

Everyone knows that Trump is a marketing genius! Okay, let’s get down to what Trump‘s real motives may be.

Both schools have one thing in common.

Neither school has a mascot.

Everybody knows that Trump is a master marketer. I think the hidden agenda will be that Trump will insist that Harvard finally adopt a formal mascot, befitting our country’s white Christian heritage: a Pilgrim, of course!

But even more importantly, this way he can get rid of that out of date logo “Veritas” and change it to “If you piss off a pilgrim, you’ll get yourself a witch trial.” Then he can raise money at halftime with a raffle where the winner gets whisked away for a lifetime in El Salvador.

Anyway, just like last year, Susan and I will be sending back Parisian commentary and pictures to celebrate our spring time and hopefully brighten yours. À bientôt!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 11, 2024 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Politics

Have you ever just stopped in the street and said to yourself, ”Wow, I wish I had that to do over!” and then found yourself exploring even larger questions?

Because of my short-lived political background, I ponder irrelevant questions and worry about them all the time.

I have some regrets.

For me it all happened back in 2014, but it only became clear what my concern should have been about two weeks ago.

Back in 2014, I was asked a question that I couldn’t answer. That was the problem.

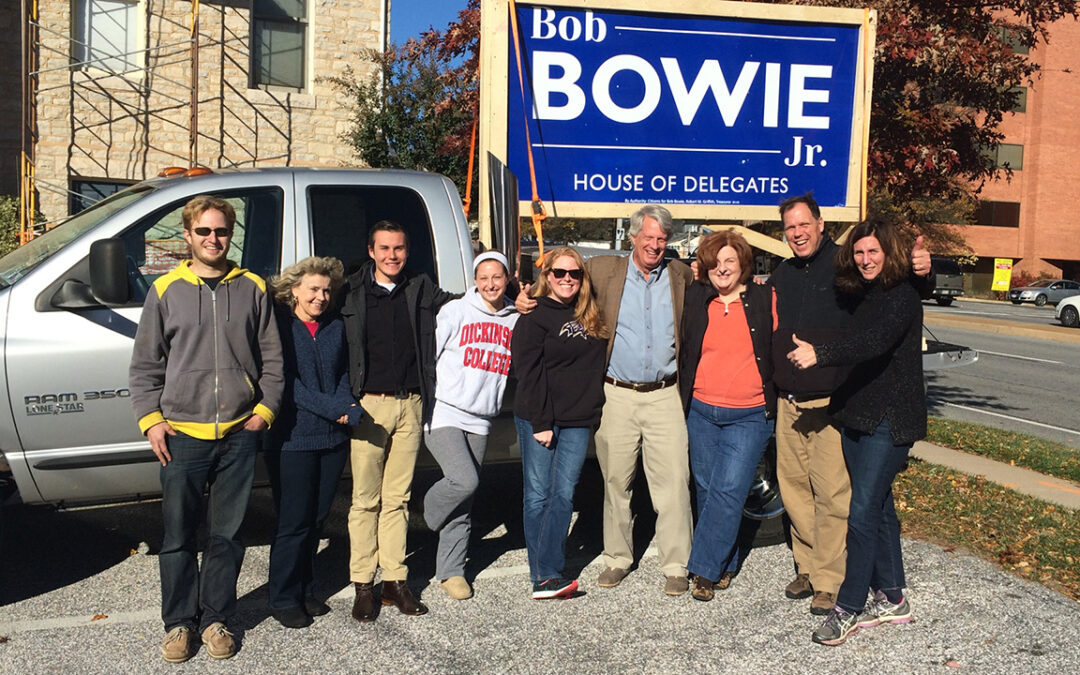

Back then, I hated gerrymandering and concluded that the country was getting dangerously divided because of it, so I ran for political office on a theme that ”We must not lose our common ground.”

My strategy would be to find common ground with every person in my divided district and thus bring them together so we could reason together.

Maryland is two-to-one Democrat and the state legislature had crammed as many Republicans as possible into the district where I lived. I am a Democrat but I was sympathetic to my outnumbered Republican neighbors. I consulted the experts and was informed that I had at best of five percent chance of winning as a Democrat in this district.

I jumped right in!

I really believed I would win if I could find some common ground each time I knocked on another door.

I was all in. I contributed my own money to the campaign and I raised over $150,000. Susan and I and a small group of overoptimistic diehards spent that summer and fall knocking on 5000 doors, and debated the three incumbents who raised only around $5,000 together. They did not need the money. They had all been in office for over a decade in this gerrymandered district.

Late one hot summer Sunday morning, it turned out I didn’t know “ common ground” as well as I thought I did. Only about two weeks ago, did it all became clear.

When I knocked on the doors, I always had the same pitch: ”I believe we must find our common ground so we can all talk together.” Then for humor I would add, because I was over 65 years old, that ”if they were worried about term limits, nature would take care of that in my case.” Everybody laughed, and we talked as friends until I was asked whether I was a Republican or a Democrat, at which point the door was slammed in my face.

Of course, I remained optimistic. As I would drive home while the sun was going down, I believed the depth of my commitment would pull me through.

The depth of my commitment was only challenged once, when I could not find “common ground.“

Late in the August heat, I knocked on the door of a well-kept home in a trailer park, which had three steps on either side of the front door.

I knocked on that door and a heavyset woman dresses in a giant muumuu answer the door and after my pitch she announced: “I can’t talk to you right now because I don’t have any underwear on.”

How was I to answer that? For the first time maybe ever, I was speechless.

I couldn’t say, “You don’t need to be wearing underwear to read my materials,” or, “No problem I’ll wait til you put on your underwear.” I was dumbfounded. I could find no common ground.

For almost ten years, I have pondered this interchange. I thought and rethought about my inability to find an answer. I have not hesitated to tell this story to others in the hope that they might suggest something. Then about two weeks ago, a friend of mine had an answer right off the top of his head!

He said, “You forgot your theme. Why didn’t you just say, “That’s okay, I don’t either!”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 21, 2023 | Featured, Law, Personal, Politics

Abraham Lincoln famously said, “You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time.”

Lincoln’s quote applies to the voting public as well as trials before a judge or jury.

Former President Trump appears to be trying to win his legal cases with political arguments. He cares little about judges, but is determined to win an election, in order to pardon himself or have another Republican pardon him if he doesn’t run. Trump is leading in the polls, so this should be easy for him to do.

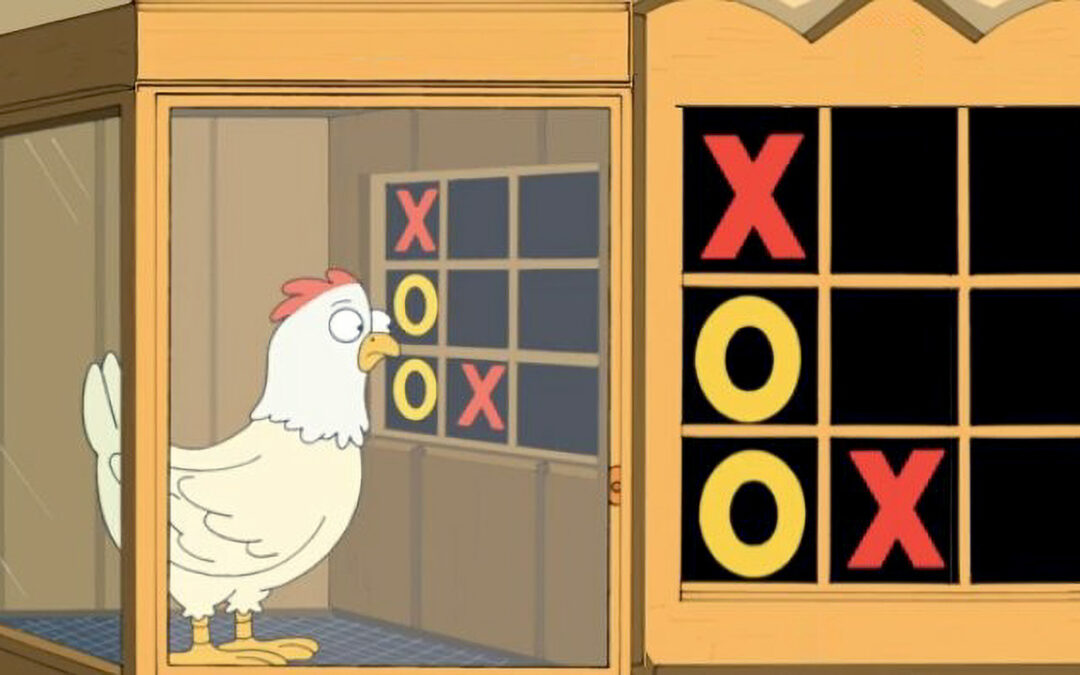

I learned how to do this from a chicken.

Years ago, I represented one defendant of four that were accused of stealing trade secrets that were provided to the lead defendant who allegedly included them in a patent for software designed for huge construction projects.

The plaintiff was a self-taught computer programmer. He was represented by a prominent New York patent firm.

The lead defendant was represented by a large Chicago law firm, which had contracted for the entire floor of an NYC hotel for the two month trial. The four trade secret defendants were represented by separate individual lawyers. I was one of them. The case was tried before a jury in the federal court in Manhattan.

I liked my client. I believed in his innocence after watching how he lived. Over the two years of depositions and trial prep, I became convinced of his innocence.

He had gotten a scholarship to college as an athlete. He struck me as a fellow who played hard, but he played by the rules. He was remarkably oblivious to how personal impressions shape jury decisions, perhaps because he was so straightforward.

The large Chicago firm gave the opening statement for the defendants that ran for a day and a half. They kept open every possible defense available and there wasn’t a defense that they didn’t like. One juror went to sleep but the lawyers seemed too busy to notice.

The other four defendants, the trade secrets defendants, each argued in their openings for at least two to three hours each, except for me.

As I watched those opening statements, I abruptly changed my strategy given the jury’s reaction to the openings.

I told the jury my opening statement would be no more than 15 minutes and whenever this trial ended, my closing summary would be no longer than 15 minutes and they would find that my client was not guilty.

I told them a little about my client and his little company, and then I sat down easily within the 15 minutes I had slotted for myself.

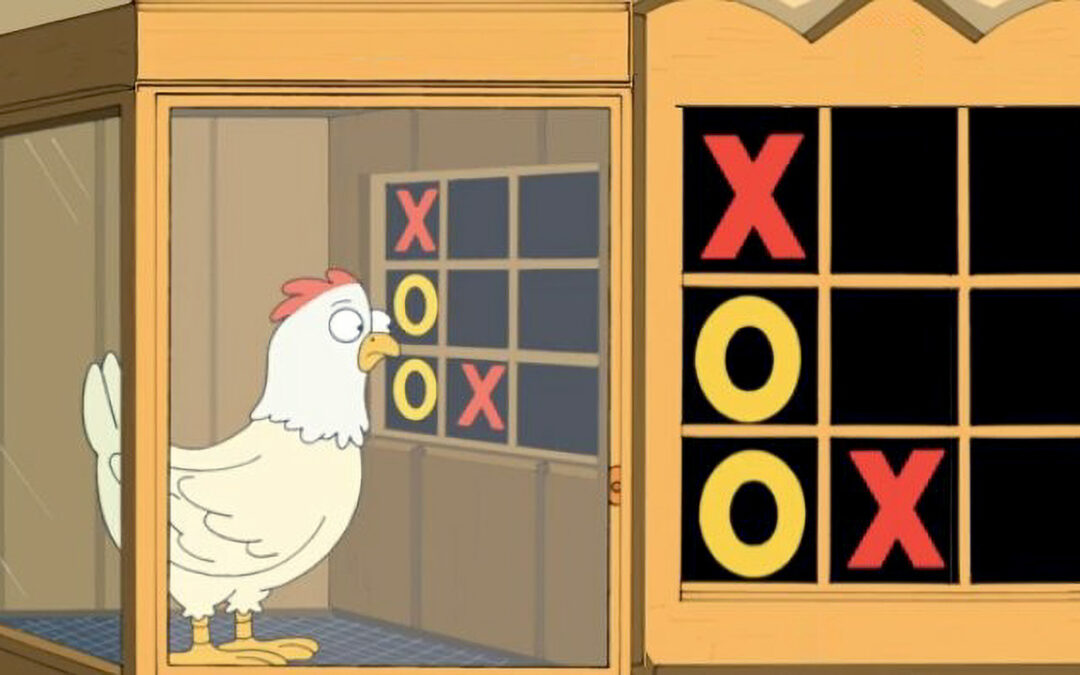

Every day of the trial, all the lawyers for the defendants went to lunch in Chinatown, which was right behind the Federal Court in Manhattan. The restaurant we went to had two attractions: 1) the dancing chicken, and 2) the chicken that would play tic-tac-toe against you.

You put the coins into the slot, and out would come the chicken. It would stare at you until you made your first move, tapping on the tic-tac-toe board that was on the glass that separated you from the chicken. An “X” would appear. The chicken would then make its counter move, pecking its choice of position, where an “O” would appear.

Even though all of the defense lawyers went to eat at this Chinese restaurant, none of them played this game because, I’m convinced, they didn’t want to dim their genius by losing to a chicken. That is certainly why I didn’t play against the chicken.

This was a serious chicken. The chicken was really good. It was so good that years later when the chicken died it got an obit in the New York Times. It was all a con job, but everyone was captivated by it. The chicken was given a signal where to pack in order to get fed, and thus peck the correct box.

As the trial progressed, I grew more worried that this case was so complicated that nobody understood it. Worse, now there were at least three jurors who were dozing off.

I became convinced that the defendants would not be considered individually. I feared that they would be lumped together with the patent defendent, and the smaller trade secret defendants would be found guilty as well, including my client.

When it became my client’s turn to testify, he came to town and, before he took the stand, we went to the Chinese restaurant. However, on the way to the men’s room, when I wasn’t looking, my client challenged the chicken.

The lawyers stopped eating and watched my client as he lost to the chicken about an hour before he was going to testify. After he lost to the chicken, everyone was remarkably quiet and nobody seemed to be eager to talk to me.

In a funny way, the loss to the chicken confirmed for me my client’s integrity and it fit quite nicely into my new strategy.

When I put him on the stand, I abandoned my prepared outline and changed gears. I kept it short, simple and direct. I flat out asked him whether he had stolen anything that became part of this purloined patent. He was surprised that I had changed our planned testimony. He replied instinctively without reservation and answered no.

I then announced that was the only question I was going to ask and then I sat down. The plaintiff never cross-examined him because he was small potatoes, and there wasn’t much testimony to cross examine.

Thereafter, I also changed gears and cross-examined the plantiff’s patent expert witnesses about the trade secrets case, which they knew nothing about. They cared only about the patent, not about the claim of trade secrets theft.

I asked each expert witness the same question: “After the years that you have put into preparation for your testimony, did you find any evidence that convinced you of my client’s guilt?” In each case, they shook their heads and answered no.

The other lawyers thought I was crazy and looked down at their papers in an effort to avoid laughter.

I added insult to injury by dramatically turning to the court reporter and saying that I wanted a copy of the answer to my question and, in each case, the court reporter nodded and I would get a couple of pages of transcript the next day.

After almost two months of trial, we went to closing, and again all the defendants gave days of closing arguments. When it came to me, I put my watch on the lectern and I looked at the jury and said, “Remember my promise of almost two months ago? I am going to give you a closing that will not exceed 15 minutes.” Then I quoted from the transcript pages that I had requested from the court reporter, the answer from each expert witness that stated they had found no evidence relating to my client.

Back then, during breaks, everybody could smoke cigarettes in the hallway. I got to know the plaintiff because he smoked a pipe and I smoked cigarettes, so we shared matches and talked.

He saw what I was doing and actually appreciated it. He would always start off after we inhaled and then, with a smile, would laugh and say, “smoke and mirrors.”

All the other lawyers waited three days for the verdict. I had to catch the train back home because I had a small trial starting the next day. After three days, the jury came down hard against all of them, but acquitted my client.

A day later I got a faxed letter from the plaintiff. He had won big, but he still sent me a letter with a smiley face and “smoke and mirrors — congratulations.”

So much of the time, appearances are more powerful and persuasive than the facts. We will see if Trump “fools the people” in the end.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jul 11, 2023 | Featured, Personal, Politics, Travel

Last month I took a trip because I wanted to “feel” what it was like to live in WWII Germany and the Soviet Cold War occupation in Czechoslovakia and Poland.

I already knew the dates, places and times from textbooks, but it’s quite different to experience what it was like to have lived during those times.

Of course the trip would come alive in museums and, unexpectedly, it brought back for me a long lost feeling I had years ago when I was just a young boy. I had gotten lost off shore in Buzzards Bay in a small motorboat that was running out of gas on an outgoing tide in thick predawn fog.

It is odd how we learn through memories and association.

How odd that museums, which were about imprisonment, brought back the feeling of drifting out to sea, creating an odd claustrophobia without barriers other than an endless borderless fog.

The claustrophobia slowly kicked in when I visited Checkpoint Charlie, the famous heavily guarded passthrough in the Berlin Wall, which kept the East Germans imprisoned inside.

It started with a set of pictures of a boy who had scrambled to climb the wall in an effort to live in freedom, but the photos chronicled how he had died riddled with bullets, hanging from barbed razor wire near the top of the wall.

How odd that I could feel claustrophobic under wide-open skies?

A few days later, the claustrophobia increased in one of the East German museums that focused on the Nazi SS and their little gray bread trucks. These had no windows, just a sliding door on one side and three closet-sized cells so small that prisoners could not stand but only sit in a narrow chair, hands by their sides, while they were taken to a concentration camp somewhere outside of Berlin.

A few days later as we traveled toward Prague, we stopped at another prison that was three or four stories high with interrogation cells on the top floor. The inmates who would not answer were showed pictures of their family who would be killed if they continued to resist.

Putin had spent six months in the house across the street when he was in Soviet intelligence, attempting to flip the tortured inmates to become Soviet spies.

The claustrophobia wrapped around me in that silent building when I realized what it must have felt like day and night in there. It was missing the noise of slamming cell doors, the echoing screams and the smell of the single bucket in the corner, which acted as a bathroom in each cramped cell, with three to a single bed and no mattress.

I know now why the feeling I had on this trip was claustrophobic but I thought it was still an odd reaction to the history of the past until I realized I had lived my whole life free in a democracy.

All of a sudden, I felt imprisonment under borderless wide open skies as a psychological imprisonment which became unbearable.

All of a sudden, I could feel the last breath of the boy crucified and bleeding from razor wire on the top of a Berlin Wall as a reaction to my claustrophobia and his death.

Years ago, as I slowly ran out of gas in my little boat, I saw the outline of a cliff as the late morning fog broke. There were connected ladders and a climbing set of stairs. I beached the boat and climbed to the top of the cliff and knocked on the door of a little cottage overlooking the ocean.

A woman with the Sunday newspaper tucked under her arm answered the door. I breathlessly asked, “Where am I?” She looked at me quizzically and answered “Menemsha,” then paused, “Martha’s Vineyard,” and then paused again… “The United States of America.”

I remember feeling happy and alive.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 25, 2022 | Featured, Personal, Politics

Fear separates heroes from cowards.

I live in beautiful northern Baltimore County west of Harford County, north of Baltimore city and south of the Pennsylvania line. It is rich with beautiful horse farms, deer and fox hunting, verdant farmland and wonderful people.

I am a moderate Democrat. Where I live is by and large Trump country but I love my neighbors. For the most part, we don’t let politics get in the way of respect and friendship.

Last week, two friends and I held a small fundraiser for a Democratic Congressional candidate who is running to unseat an incumbent Trump Republican who met in the White House to plan the January 6th attack on the Capital.

As the midterms have been approaching, for some reason, I have been remembering old litigation from when I had been hired by a prominent personal injury lawyer to try the cases he thought he would lose.

I wanted to learn how to try cases before I started my own firm in 1990, so this was perfect and I took the job.

In the 1980s, the Harford County Courthouse was being renovated. An alternative courthouse annex was set up to handle cases while the renovations proceeded.

This temporary courthouse had a makeshift heating air conditioning and ventilation system hung from the ceiling, and the sounds from other courtrooms and the neighboring bathroom could be heard through this system during the proceedings.

I had been assigned a case which my employer had said was “difficult.” Our client, a young-for-his-age teenage boy, was so shy he could barely answer my questions about his bicycle accident during our first meeting.

The accident involved a car and the boy had his leg broken and his bicycle destroyed. There were real questions about who was at fault. His parents filed on his behalf, and without his knowledge, a lawsuit for extensive damages.

The boy had no friends and was so shy that his only freedom came when he left school in the afternoon to ride his bike for hours along country roads while his classmates played seasonal team sports.

His parents were clearly disappointed by their son. He would never be the football captain or the class president.

I met him with his parents for trial preparation about a week before trial. After we went over the case that had been filed, the boy seemed reticent and I asked his parents to leave the room. I asked him to go over the facts once more with me one on one. He looked down and repeated what his parents had told me before they had left the room. He was uncomfortable, but what was striking about him was that when his eyes met mine and he told me something, he was honest, definitive, and straightforward.

I feared this was a boy who was being forced to tell a story instead of the truth.

He clearly was not looking forward to testifying under oath.

On the day of trial, I asked his parents to bring him to the courthouse early so that he could sit in the witness chair alone without anybody there, to familiarize himself with the space and settle his nerves.

When he sat alone in that witness chair he was terrified. I wanted his parents to see him sitting there alone staring into space and shaking before anybody else came into that courtroom.

I then asked him to go sit with his parents so we could talk about the possibility that the case could be settled before trial. The parents refused and reiterated that they wanted several hundred thousand dollars in damages.

Several minutes later, the opposing counsel came in and started to set up for the trial. Shortly thereafter, the people who would be chosen as jurors filtered in.

The boy become more and more frightened. About 10 minutes before the judge would appear and we would pick a jury, the boy slowly started to cry by himself. I noticed that the parents were trying to cover this up, and they asked to remove him briefly from the courtroom to go to the bathroom so he could compose himself.

The defense counsel had offered nothing to settle the case, because he believed that the boy was too shy to make a good impression before the jury. He ambled over and offered a nominal amount to resolve the case, which is not unusual before a case begins.

All of a sudden, through the heating ducts from the bathroom, the sound of gagging and then a toilet repeatedly flushing could be heard.

The defense counsel asked where was the boy. I said I was sure he would be back before the judge entered and we started picking a jury.

Moments later, the boy’s father came into the courtroom and signaled for me to join him in the hall. He told me the boy had refused to testify but his father instructed me that he was going to make sure he did.

I asked the father to consider a settlement of the case, because the boy clearly was uncomfortable with testifying to something that apparently he did not believe was true. The father said he would consult his wife. I insisted that whatever decision was made had to be given to me by my client, their son.

He hurried off to the bathroom and returned with his wife who agreed that the boy would be ready to testify.

I told them to get their son. They told me to come into the men’s room because he wouldn’t leave his stall.

The boy looked at me when he came out of the stall, tears streaming down his face. He looked down and wouldn’t talk. I looked at him and said, do you want me to resolve this case? And he nodded. His parents objected. I push them aside. What do you think is a fair settlement, I asked. He waved his hands as if to say nothing. I told him that the other side had made a nominal offer to merely resolve the case and I asked him whether I could negotiate further and resolve it rather than dismiss it. His parents resisted, but he nodded yes.

When I reentered the courtroom the sound of the toilet flushing was coming through the ductwork and there were muffled heated voices also coming through.

The defense counsel asked again where was my client. The judge was about to enter. I joked that if he only had offered a little more money, maybe it could have been resolved. He added to his offer. I told him I was authorized to settle the case for double that amount and we did.

It wasn’t much. It was a compromise. Enough to pay some hospital bills and get a replacement bicycle for the boy.

It only took about 10 or 15 minutes to put the settlement on the record and send the jury home. I left the courthouse and looked for the boy and his parents. Their car was gone and I never saw them again.

I wish I could have said goodbye to that boy who was too shy to confront the world, but had the courage to stand his ground and refuse to lie!

Fear separates the heroes from the cowards.

Two days ago, after our little political fundraiser, my friend and his wife, who had held the reception at their home, woke up to find a dead fox hung from their mailbox.

This is not who we are in northern Baltimore County.

This not who we are as Americans.