by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 17, 2025 | Featured, General, Humor, Law, Personal, Politics

When I started to practice law, Jimmy Carter was elected president. To avoid some unimaginable conflict of interest, he sold his family farm for peanuts. Since I retired from the practice of law 10 years ago, apparently the ethics have changed.

President Trump for his birthday last week gave himself a military parade, which which cost the American taxpayers approximately $25 million and tore up the streets of Washington.

Several news services have recently reported that since the early days of President Trump‘s reelection campaign he has made more than double his net worth, about $5.4 billion dollars.

In the past, I would’ve been horrified, but now my reaction is that it’s a shame I didn’t somehow make a bigger profit back when ethics prohibited me.

Back during those ethical times I would preach to the lawyers at my firm that the easiest way to check your professional ethics is to ask yourself if what you were about to do would be embarrassing if it would become a headline in the New York Times. If so, don’t do it.

President Trump has re-organized and turned upside down the professional ethics of the presidency and the ethics I was used to. Everything unethical or untrue that Trump has done now is routinely front page headlines on the New York Times, which nobody reads anymore.

I have gone back to thinking about how rich I would be if I’d taken on cases that I ultimately rejected long ago because of ethical concerns.

Consider the amount of money I could’ve made if I had taken that case long ago of two Hindu businessmen who came into the office and told me they wanted to incorporate (for personal liability reasons) an ongoing business that provided Hindu Americans a chance to bury their families in the Ganges River for about $5,000 per loved one.

They told me that the contract that they offered guaranteed that the loved ones ashes, with which they were entrusted, would be respectfully sent to the Ganges, a boat would be hired as well as a videographer to make a movie of the ceremony as the ashes were transported in a beautiful urn, and a man rowing the boat out in the Ganges would be filmed opening the container and emptying it so the ashes were visible as they were were gently poured into the river.

The $5,000 would be collected in exchange for the video of the ceremony.

I will admit I was intrigued by this novel, religious practice and I asked about the heavy cost of the procedure and the profit they were making per contract.

Without batting an eye both businessmen looked at me and said it was about 95% profit. I asked them how could they possibly make such a profit and they answered: “We send everyone the same video.”

If you’re using the same video and you are making a 95% profit you certainly don’t have to be greedy. You could include a beautiful hologram of the soul rising from the Ganges and fluttering off into reincarnation.

Also they completely missed the opportunity for relics, swag, and real cool T-shirts.

When you include the total Trump’s family and political friends have made in the “pay to play” access and favors, which have included the opportunity to show your personal love and respect by purchasing Trump bitcoin and Trump Bibles, and such gifts as an airplane from the government of Qatar, no wonder Trump wants a third term.

I was so stupid I refused to represent the two Hindu businessmen, even though they generously offered me a free burial in the Ganges.

I could also have befriended the President by referring him to another client who I rejected. For a while, “viatical contracts” were easy money. Several people had the idea at the same time. During the AIDS epidemic several entrepreneurs were going into hospitals or hospices and offering to buy life insurance policies at about 10% of their face value from those who would soon die. There’s nothing illegal about that, but for me it didn’t pass the smell test.

There is some justice in the world. Once effective HIV treatment became available, they were stuck continually paying for ongoing life insurance policies.

I suspect that the Trump family has already seen the future of medical profit as is evident from the appointment of Robert Kennedy, Jr. and the future of TMD (Trump Measles Deterrent). This is not a vaccine. it is free and called “The Trump Blessing,” which is administered over a Zoom call after you buy some of the remaining overstocked Bibles that will become collectors items soon.

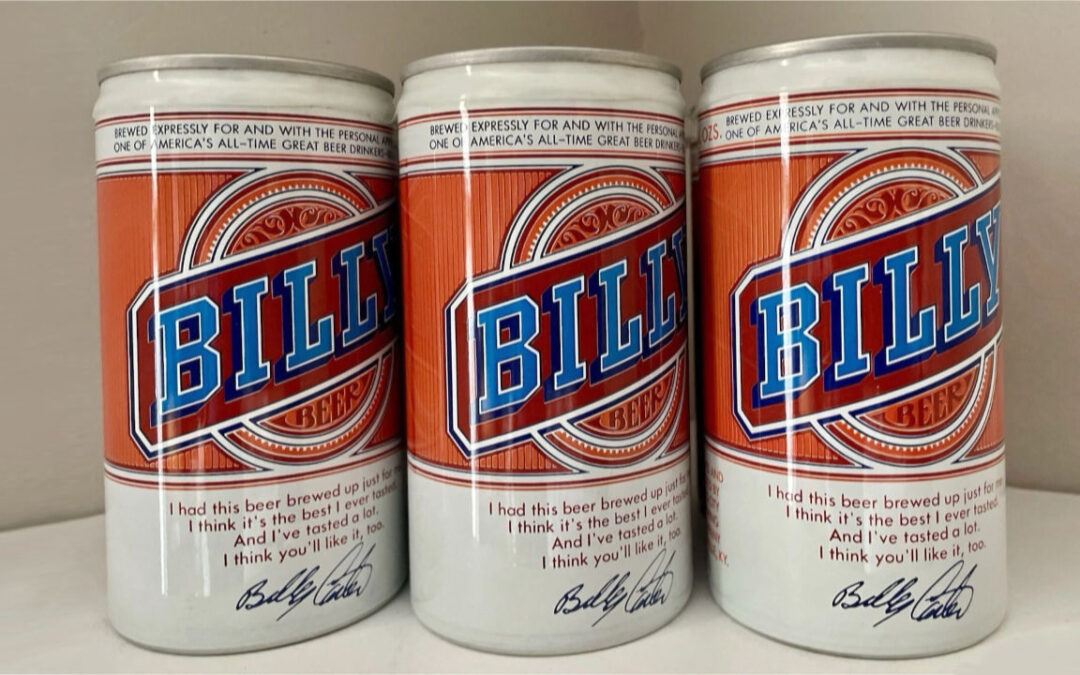

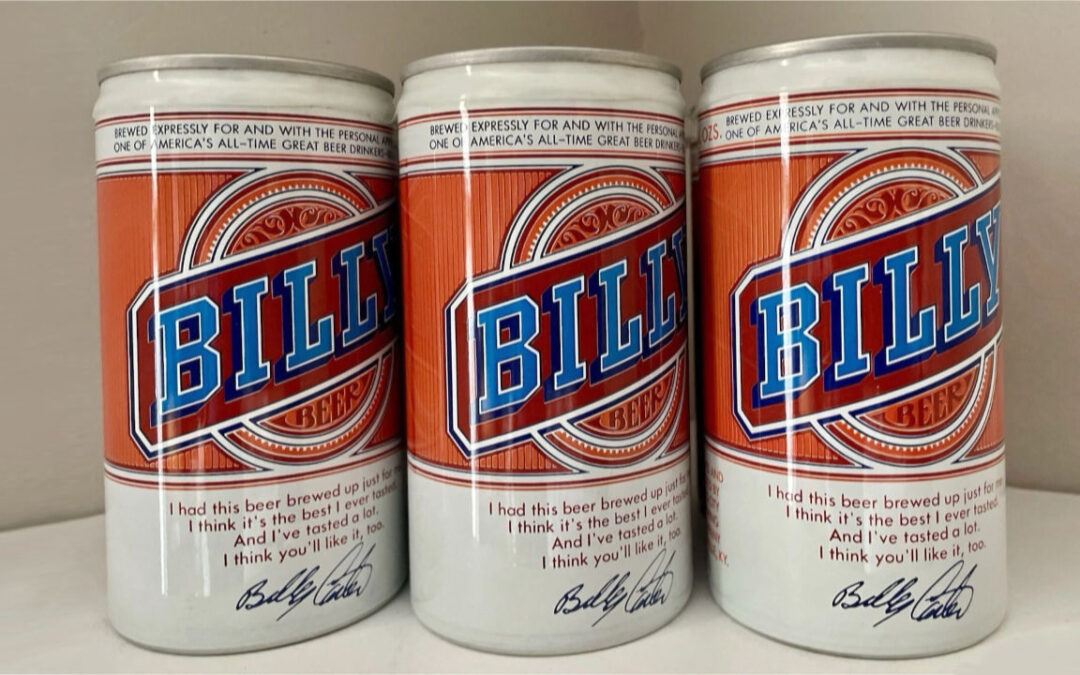

I think the only benefit Jimmy Carter received from his presidency was a gift given by his brother: a couple of cans of Billy Beer.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | May 27, 2025 | Featured, Humor, Personal

Have you been following the economics of this country recently?

Guess who was invited to President Trump’s private event for customers of his cryptocurrency business on Thursday and given a White House tour on Friday?

I wasn’t!

I called my friends, Peter, Belinda and Liza, to see if they had been part of this same oversight by the President.

Peter, Belinda and Liza and I were neighbors during our middle school years and have been friends ever since for over 60 years, and all of us were there from the beginning of cryptocurrency.

They weren’t invited either!

We concluded that this oversight by the President was not his fault and was due to only one possible interpretation.

Our President does not know a lot of American history or, to be a little more polite, he has not yet become aware of the true history of cryptocurrency.

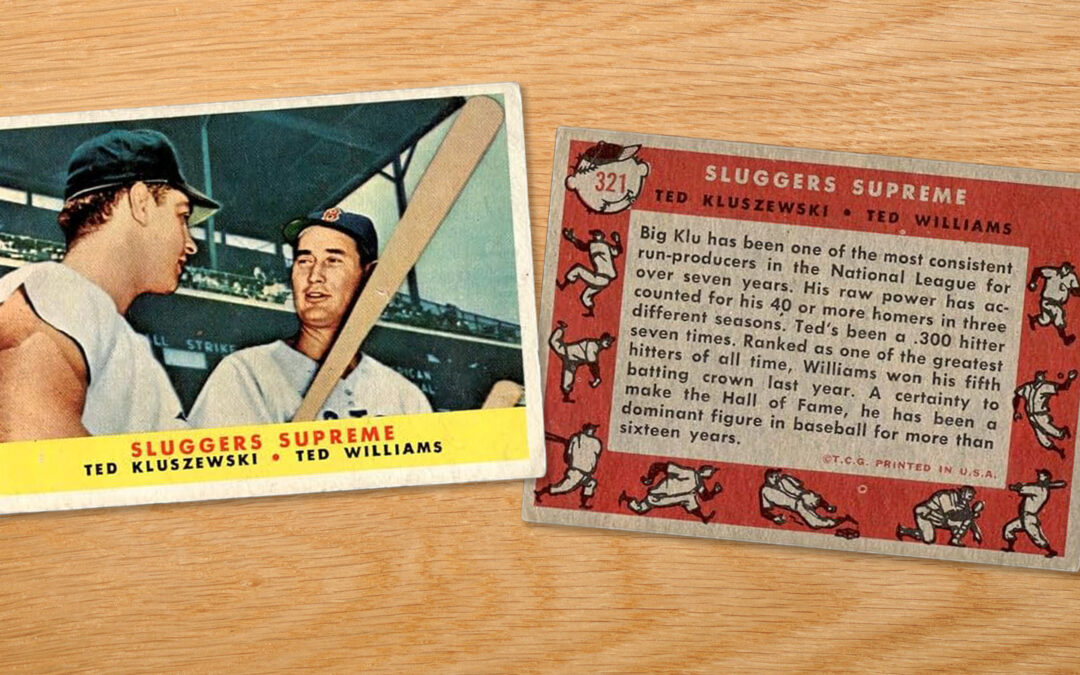

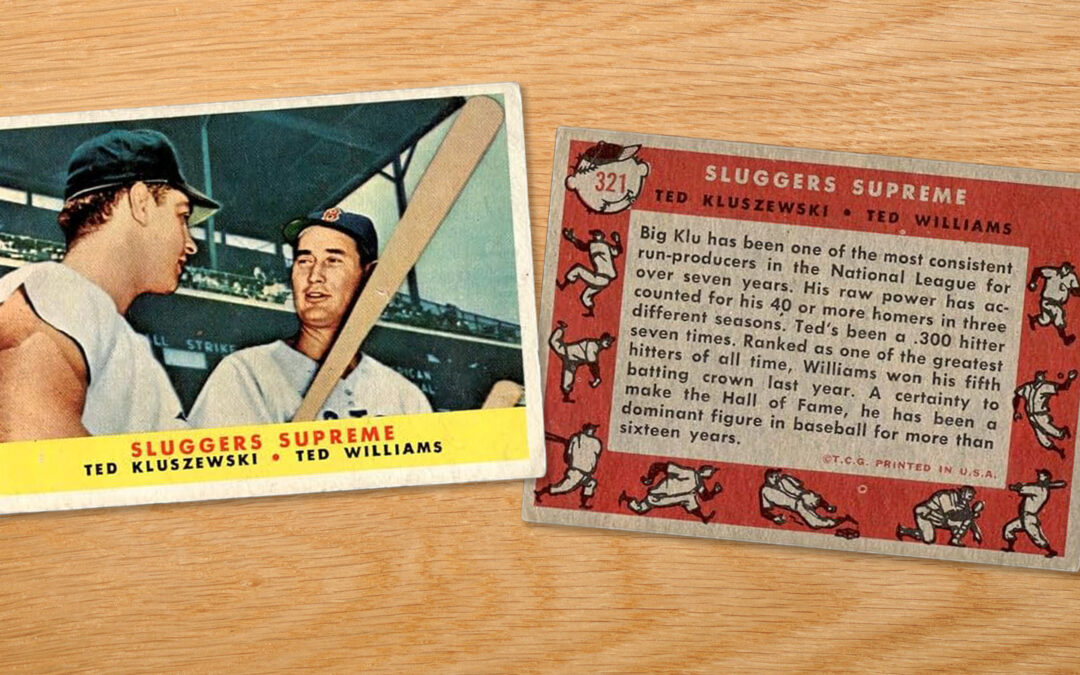

As the rest of us already know, cryptocurrency was quietly created after Nixon took the country off the gold standard. Quite conveniently, it was the same time the first Topps baseball cards were issued in five-card packs with a card size slab of bubblegum included.

The retail cost was five cents per pack. A penny for each card and the bubblegum was free — age appropriate pre-pubescent genius marketing.

A half century before cryptocurrency entered the world stock market, Peter and I were both early investors in baseball cards, and then found another lucrative market in marble monopolies. We were early traders in pre-crypto middle school cards and marbles during recess.

Peter cornered the marble market so effectively that the marble market collapsed after he won all the marbles.

I tried to make a run on “big marbles” so I dressed up my little middle school self and went to pawn shops and antique stores looking for clear round door knobs.

Regrettably, no door knobs are completely round and thus valueless in the larger marble markets.

As a result — for the good of the market — Peter gave a written announcement handed out to the neighborhood that he would be emptying several boxes of marbles to the neighborhood market for free one late spring Saturday afternoon. It happened out of a second floor window with the driveway below. It was an early example of flooding the market.

Peter emptied five bankers boxes of multi currency marbles, including “puresy boulders” and several stunning “jumbo spirals.” The market was saved and Peter had made recess fun again.

Baseball cards back then were “to die for,” particularly if you had a complete set. Peter had a complete set of baseball cards for the years 1957, 1958, and 1959.

Even in middle school, you knew these people were serious people! Peter was a born collector and became a well known New York art dealer. Liza became a respected museum curator in Washington DC, and Belinda became a brilliant art writer and critic.

In the alternative, when I went off to college, my mother emptied my closets and threw away all of my marbles and baseball cards… and I became a lawyer.

At the same time as Trump’s cryptocurrency banquet and tour of the White House, his administration announced that they would be retiring the penny because it was not cost-effective to produce it anymore. They had determined that it took four cents to produce a penny. Think about the appreciated value of just one card, bought for a penny. Or even better, a complete set.

Ever since Nixon took us off the gold standard, our currency, stocks and bonds, like cryptocurrency, have no value other than the theoretical value according to the market.

However, with marbles and baseball cards, unlike cryptocurrency, there is the added component of artistic beauty. They are self valuing and hold a valuable historical record on the flip side of the picture — batting average and stolen bases and other stats.

Also, the bubble gum is great for the dental economy.

Hold onto your baseball cards and don’t lose your marbles!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | May 20, 2025 | Featured, Personal, Travel

When Susan and I flew to Paris again this year for three weeks this spring, I had planned to watch the Bob Dylan movie, “A Complete Unknown” on the flight that night, but I was too tired so I slept instead.

Paris was warming to its spring as we landed at Charles De Gaul airport and traveled into the heart of Paris to a beautiful flat with its view of the Seine from its fifth floor living room and bedroom windows on the Île Saint-Louis.

The six hour difference in the time between the East Coast of the United States and Paris delayed the news reports that poured into my cell phone at three in the afternoon Paris time as America woke up and went to work.

The distance and the time change diminished my obsession to keep up with America’s politics, but nothing could uncouple it from my daily concerns.

Over our three weeks, Susan and I committed to walk the city, but for longer trips to Montmartre or the outskirts of Paris to the Louis Vuitton Museum to see the huge new David Hockney exhibit, we took the Metro.

Each evening, we would go to one of the little restaurants on Île Saint-Louis and then climb the stairs or take the little elevator to the flat to read the news before bed.

Last year. we had taken three days off from Paris to go to the LaVar Valley to stay in a beautiful Château and visit the region’s medieval history. This year, we went to Normandy and, as I observed the beaches and cliffs, and finally the dramatic American cemetery, the pride I’ve always felt for America rekindled with my respect.

On the morning that we flew back in mid May, Paris was in full bloom as we got on the plane to fly into the upcoming day on our return to the United States.

I again committed to watch the Bob Dylan movie on our way home.

Even though it had been out for some time, I still had not seen it, but I knew enough from the reviews that it was about the transition from Dylan’s early folk years to the electric folk rock that Dylan made in 1965.

In the fall of 1965, I had started my first year at the Cambridge School of Weston, a progressive high school that knew something about learning disorders and thus was unlike the boarding schools and summer schools I had attended previously.

It was my second try at 11th grade. My new school was so very different in so many ways, but as my classmates wore sandals and blue jeans and played guitars out on the quad or went off to the ceramic studio and the wide range of classes offered, I attended my classes in a sport jacket, but eventually gave up on the tie.

I believed I was in transition to a better place and I believed that from the start. I was hoping that repeating the 11th grade would rekindle my love of learning in a new environment with a fresh start.

Within weeks of my first day, a sign-up sheet went up in the dining room, which offered tickets and a bus ride provided by the school to see Bob Dylan play in a Boston theater.

I signed up with about 15 of my fellow students and we got on a little bus to go down to the theater.

When we got to the venue in downtown Boston, we were told that it had been sold out almost immediately and, though we had paid for our tickets, no seats had been assigned for us.

The theater instantly took action and placed folding chairs in a semicircle on stage directly behind Bob Dylan.

The first half of the performance was all Bob Dylan singing his folk songs in front of an adoring audience with us directly behind him.

When the audience returned to their seats for the second half of the program, however, a rock ’n’ roll band was now set up to back up Dylan. We pushed our seats back further to accommodate the instruments and cables.

When Dylan entered, he was met with catcalls. I could not believe what was happening in front of me. I sat, self-conscious and a little bit frightened, as Dylan faced the catcalling audience.

Dylan played the first few songs with the electrical back up in the midst of the continuing catcalls.

Somewhere in the middle of one of those songs, a very loud voice broke through and yelled something like, “You sold out!”

Dylan stopped the performance. After a very awkward moment, the silence was broken by Dylan’s voice over the microphone:

“I don’t believe you!” he said, and there was a smattering of applause as he signaled to start the song again, resuming the concert.

As the movie portrayed the transition at the Newport Folk Festival from folk to folk rock, Dylan spoke those same lines to that hostile audience and I returned momentarily to being a teenager on the back of that stage. But I was proud to be there rather than surprised and frightened by the event.

As we landed at Dulles Airport in Washington DC, and returned to our political world, I felt reborn and re-nourished by the experience.

I had this very odd feeling that these juxtapositions had reawakened me to the messy but resilient democracy in which I have been fortunate to have lived and prospered.

Somehow, America, through its history, has been endlessly capable of being reborn, newly appreciative of what the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution have provided for each generation.

Shortly thereafter, I laughed when the news reported that Harvard University had discovered in its archives an original copy of the Magna Carta, which had been presumed to be a copy, purchased in England for less than $30 after the Second World War. It turned out to be the thing itself.

It was a great trip to Paris, which taught me yet again how much I love this country.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 16, 2025 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Politics, Travel

I’m not really worried about Trump taking over Harvard, so Susan and I are going to Paris this Saturday for a couple of weeks.

Why is everybody so upset? It seems like all the commentators have completely overlooked Trump’s leadership skills when he ran Trump University.

Trump has been very vocal about his business acumen and, by his own account, he ran the university brilliantly for the five years before its bankruptcy.

There was some unsubstantiated criticism about gold toilet seats, but he claimed he was always very hands-on and was good at keeping the overhead low.

For example, despite its name, Trump University was never an accredited university or college. It did not confer college credit, grant degrees, or grade its students.

Think about the savings on the cost of paper.

In contrast, the data from the 2023–24 academic year, 72% of Harvard University’s first-time, full-time undergraduates received financial aid. In the alternative, Trump University was apparently so popular, it never needed to offer scholarships. And Trump has already said that he wants to get rid of Harvard’s nonprofit status.

Really! So where is the art of the deal?

Harvard is not effectively selling its product! No. Harvard has been giving it away for free.

What is also great is that Trump has the experience to navigate these litigious times. In 2011, Trump University became the subject of an inquiry by the New York Attorney General’s office for illegal business practices, which resulted in a lawsuit filed in August, 2013. It was also the subject of two class actions in federal court. The lawsuits centered on allegations that Trump University defrauded its students by using misleading marketing practices and engaging in aggressive sales tactics.

Of course!

Everyone knows that Trump is a marketing genius! Okay, let’s get down to what Trump‘s real motives may be.

Both schools have one thing in common.

Neither school has a mascot.

Everybody knows that Trump is a master marketer. I think the hidden agenda will be that Trump will insist that Harvard finally adopt a formal mascot, befitting our country’s white Christian heritage: a Pilgrim, of course!

But even more importantly, this way he can get rid of that out of date logo “Veritas” and change it to “If you piss off a pilgrim, you’ll get yourself a witch trial.” Then he can raise money at halftime with a raffle where the winner gets whisked away for a lifetime in El Salvador.

Anyway, just like last year, Susan and I will be sending back Parisian commentary and pictures to celebrate our spring time and hopefully brighten yours. À bientôt!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Mar 25, 2025 | Featured, Humor, Poetry

If you’re like me, the best memory you ever have had is an act of self-deception that you can’t remember. However, if you happen to stop forgetting for only a fraction of second it will be abrupt recollection.

It is like if you have ever accidentally slammed a door in your own face. It’s not easy to do, but you’ll remember it if you succeed.

On the first day of spring this year, I had one of those abrupt remembrances.

My New Year’s resolution this year is to get into better physical shape this spring. Unconsciously, of course, I have been getting less and less inclined the closer I get to springtime when I must start fulfilling my commitment to myself.

The truth is this New Year’s resolution has been the same New Year’s resolution I have made each year for over 20 years, but each previous spring I had successfully forgotten that years’s resolution.

Then I stumbled upon one of the sonnets in the book I wrote more than 20 years ago, entitled “Marathon Man.”

This year the door slammed in my face. Coincidentally, it occurred on the first day of spring last week, at a doctor’s appointment when I was told I must start exercising. I had forgotten that over 20 years ago I wrote “Marathon Man.” which made it much worse.

It starts:

The Marathon Man

“In a world of educated guesses

About one’s loves, integrity and health,

It is my custom to keep promises,

Even if they are only to myself.”

This is the perfect example of delusions of grandeur, which I had pleasantly forgotten into a magnificent memory of never committing to exercise, which is regrettably false.

As early as I can remember, I have consistently joked that I was so lazy I played goalie in all sports to avoid running laps. (The coach always shoots on the goalie while the rest of the team runs laps.)

But in my defense, technically being a goalie is not about the commitment to never exercise. It is a commitment not to exercise that I practiced religiously. I never committed to exercise. That’s entirely different.

Nonetheless, I’m highly competitive.

My memory is that I have saved myself from exercise to avoid injury so I will be ready for the senior Olympics when some doctor finally tells me I must exercise.

I have been told this before over 20 years ago when I was the marathon man but still as lazy and competitive as always.

Back then, I challenged a friend who is a very good runner to a 10 K race, but I got a 10-minute reduction of my time as a handicap to even the odds. For about three weeks before the race, I committed to run a mile around the high school track and, as a further commitment, I would eat four raw eggs poured out of a blender because I had seen “Rocky” the movie and Rocky did that.

It didn’t go well, which led to the delusion of grandeur in the form of a marathon. As is indicated in the third stanza:

“I trained on a treadmill, March to July.

Got my first runner’s high at 55.

Depleted my life‘s endorphin supply,

and blew out both knees and begged to die.“

So this time the doctor prescribed a certain number of steps as a target for each day. The doctor reminded me hopefully that it would also get me outdoors and into sunlight neither of which happened.

At the end of every day around midnight, before bed, I would find myself doing endless laps around the dining room table to meet my minimum requirement of steps.

Covid helped me along. My wife, who exercises regularly, proudly told me one evening her total steps and asked me about mine. I had decided to take the day off, so I happily worked and read pretty much all day. My total step count was around 50. Which probably is two trips to the bathroom and one to the kitchen.

Then I ran into this damn poem and I don’t feel good about getting ready for the senior Olympics. I feel my lethargy has not sufficiently ripened.

The sonnet ended with this final couplet:

“Oh yes, but the hell with all this fun;

Next year, for sure, I’ll be ready to run.”

— “An Accidental Diary: A Sonnet a Week for a Year” by Robert Bowie, Jr.

https://a.co/eg2uDCx

That was 20 years ago. No escaping it now. The door slammed in my face.

I guess I better go try to find my shoes.