by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 17, 2025 | Featured, General, Humor, Law, Personal, Politics

When I started to practice law, Jimmy Carter was elected president. To avoid some unimaginable conflict of interest, he sold his family farm for peanuts. Since I retired from the practice of law 10 years ago, apparently the ethics have changed.

President Trump for his birthday last week gave himself a military parade, which which cost the American taxpayers approximately $25 million and tore up the streets of Washington.

Several news services have recently reported that since the early days of President Trump‘s reelection campaign he has made more than double his net worth, about $5.4 billion dollars.

In the past, I would’ve been horrified, but now my reaction is that it’s a shame I didn’t somehow make a bigger profit back when ethics prohibited me.

Back during those ethical times I would preach to the lawyers at my firm that the easiest way to check your professional ethics is to ask yourself if what you were about to do would be embarrassing if it would become a headline in the New York Times. If so, don’t do it.

President Trump has re-organized and turned upside down the professional ethics of the presidency and the ethics I was used to. Everything unethical or untrue that Trump has done now is routinely front page headlines on the New York Times, which nobody reads anymore.

I have gone back to thinking about how rich I would be if I’d taken on cases that I ultimately rejected long ago because of ethical concerns.

Consider the amount of money I could’ve made if I had taken that case long ago of two Hindu businessmen who came into the office and told me they wanted to incorporate (for personal liability reasons) an ongoing business that provided Hindu Americans a chance to bury their families in the Ganges River for about $5,000 per loved one.

They told me that the contract that they offered guaranteed that the loved ones ashes, with which they were entrusted, would be respectfully sent to the Ganges, a boat would be hired as well as a videographer to make a movie of the ceremony as the ashes were transported in a beautiful urn, and a man rowing the boat out in the Ganges would be filmed opening the container and emptying it so the ashes were visible as they were were gently poured into the river.

The $5,000 would be collected in exchange for the video of the ceremony.

I will admit I was intrigued by this novel, religious practice and I asked about the heavy cost of the procedure and the profit they were making per contract.

Without batting an eye both businessmen looked at me and said it was about 95% profit. I asked them how could they possibly make such a profit and they answered: “We send everyone the same video.”

If you’re using the same video and you are making a 95% profit you certainly don’t have to be greedy. You could include a beautiful hologram of the soul rising from the Ganges and fluttering off into reincarnation.

Also they completely missed the opportunity for relics, swag, and real cool T-shirts.

When you include the total Trump’s family and political friends have made in the “pay to play” access and favors, which have included the opportunity to show your personal love and respect by purchasing Trump bitcoin and Trump Bibles, and such gifts as an airplane from the government of Qatar, no wonder Trump wants a third term.

I was so stupid I refused to represent the two Hindu businessmen, even though they generously offered me a free burial in the Ganges.

I could also have befriended the President by referring him to another client who I rejected. For a while, “viatical contracts” were easy money. Several people had the idea at the same time. During the AIDS epidemic several entrepreneurs were going into hospitals or hospices and offering to buy life insurance policies at about 10% of their face value from those who would soon die. There’s nothing illegal about that, but for me it didn’t pass the smell test.

There is some justice in the world. Once effective HIV treatment became available, they were stuck continually paying for ongoing life insurance policies.

I suspect that the Trump family has already seen the future of medical profit as is evident from the appointment of Robert Kennedy, Jr. and the future of TMD (Trump Measles Deterrent). This is not a vaccine. it is free and called “The Trump Blessing,” which is administered over a Zoom call after you buy some of the remaining overstocked Bibles that will become collectors items soon.

I think the only benefit Jimmy Carter received from his presidency was a gift given by his brother: a couple of cans of Billy Beer.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jan 21, 2025 | General

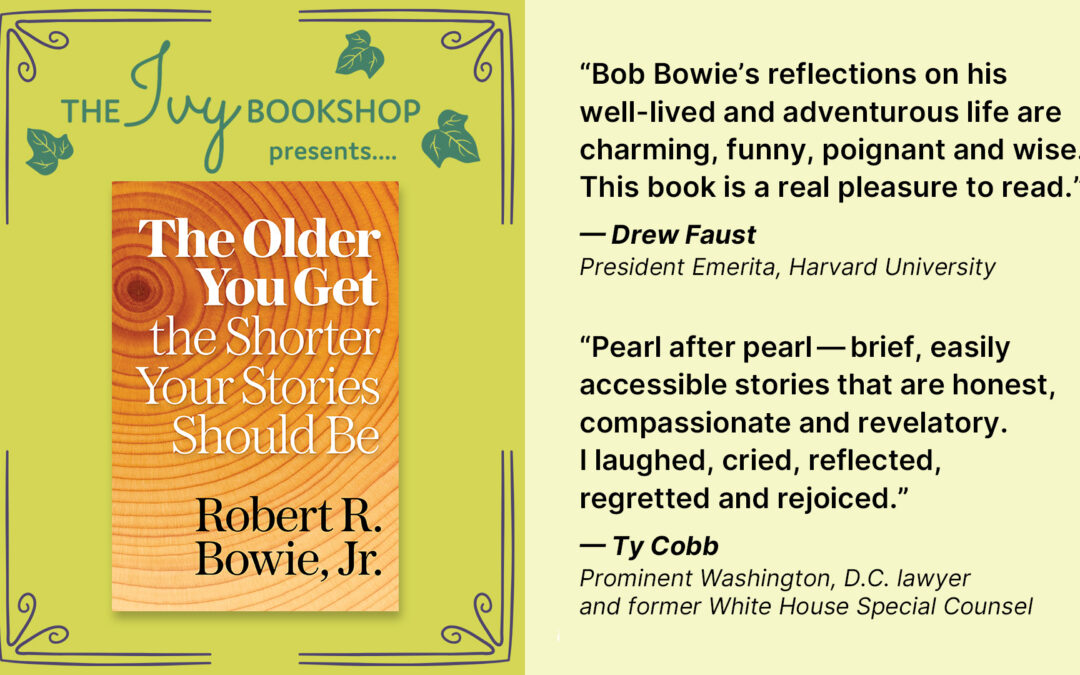

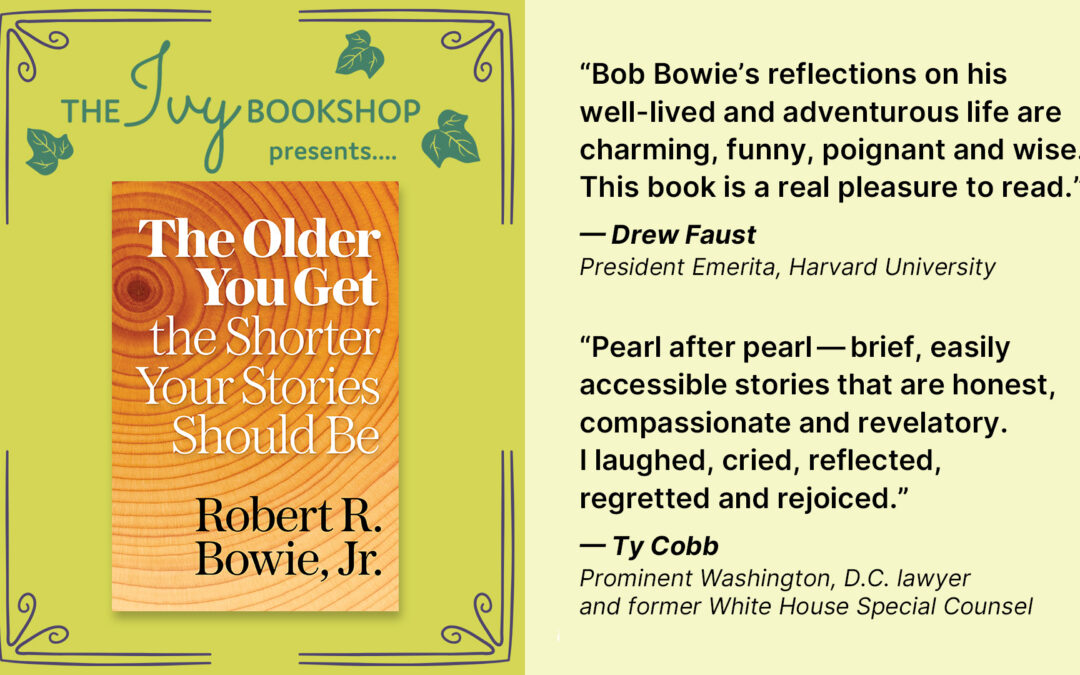

I am an American, who loves our country, but hates its present polarization. I have not written about politics over the last several months because I have been putting together and marketing my book “The Older You Get the Shorter Your Stories Should Be.” However, any chance at humor will break down my resolve to avoid politics and be politically incorrect.

Today I couldn’t resist the humorous head-on collision of President Trump being sworn in (without his hand on the Bible) at the same spot where almost 50 years ago, Jimmy Carter, a devote Christian, was sworn in as our 39th president. But it got more ironic after Donald Trump was sworn in where four years before he had led an insurrection to overthrow the election that he had lost and, within hours after being sworn in, signed an executive order releasing 1500 people convicted of the insurrection. It made me laugh to think of poor Jimmy rolling over face down, as he lay in state.

Of course, my observation was random this morning because I had been randomly leafing through the section of the book entitled “It Can’t Happen Here” and found, on page 159, “Back to the Future.”

What made me laugh and write this now was a feeling of claustrophobia, which made no sense. I know this is dark and perhaps inappropriate, but we still have to figure out how we can all laugh together again at the absurdity of all this irony.

—

Back to the Future

Last month I took a trip because I wanted to “feel” what it was like to live in WWII Germany and the Soviet Cold War occupation in Czechoslovakia and Poland.

I already knew the dates, places and times from textbooks, but it’s quite different to experience what it was like to have lived during those times.

Of course the trip would come alive in museums and, unexpectedly, it brought back for me a long lost feeling I had years ago when I was just a young boy. I had gotten lost off shore in Buzzards Bay in a small motorboat that was running out of gas on an outgoing tide in thick predawn fog.

It is odd how we learn through memories and association.

How odd that museums, which were about imprisonment, brought back the feeling of drifting out to sea, creating an odd claustrophobia without barriers other than an endless borderless fog.

The claustrophobia slowly kicked in when I visited Checkpoint Charlie, the famous heavily guarded passthrough in the Berlin Wall, which kept the East Germans imprisoned inside.

It started with a set of pictures of a boy who had scrambled to climb the wall in an effort to live in freedom, but the photos chronicled how he had died riddled with bullets, hanging from barbed razor wire near the top of the wall.

How odd that I could feel claustrophobic under wide-open skies?

A few days later, the claustrophobia increased in one of the East German museums that focused on the Nazi SS and their little gray bread trucks. These had no windows, just a sliding door on one side and three closet-sized cells so small that prisoners could not stand but only sit in a narrow chair, hands by their sides, while they were taken to a concentration camp somewhere outside of Berlin.

A few days later as we traveled toward Prague, we stopped at another prison that was three or four stories high with interrogation cells on the top floor. The inmates who would not answer were showed pictures of their family who would be killed if they continued to resist.

Putin had spent six months in the house across the street when he was in Soviet intelligence, attempting to flip the tortured inmates to become Soviet spies.

The claustrophobia wrapped around me in that silent building when I realized what it must have felt like day and night in there. It was missing the noise of slamming cell doors, the echoing screams and the smell of the single bucket in the corner, which acted as a bathroom in each cramped cell, with three to a single bed and no mattress.

I know now why the feeling I had on this trip was claustrophobic but I thought it was still an odd reaction to the history of the past until I realized I had lived my whole life free in a democracy.

All of a sudden, I felt imprisonment under borderless wide open skies as a psychological imprisonment which became unbearable.

All of a sudden, I could feel the last breath of the boy crucified and bleeding from razor wire on the top of a Berlin Wall as a reaction to my claustrophobia and his death.

Years ago, as I slowly ran out of gas in my little boat, I saw the outline of a cliff as the late morning fog broke. There were connected ladders and a climbing set of stairs. I beached the boat and climbed to the top of the cliff and knocked on the door of a little cottage overlooking the ocean.

A woman with the Sunday newspaper tucked under her arm answered the door. I breathlessly asked, “Where am I?” She looked at me quizzically and answered “Menemsha,” then paused, “Martha’s Vineyard,” and then paused again… “The United States of America.”

I remember feeling happy and alive.

—

My only hope is that we can end this polarization with the brilliance of our democracy as we go into the future.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Dec 3, 2024 | Featured, General, Personal, Shorter Stories Book, Travel

If you’re tired of Black Friday, Small Business Saturday, Cyber Monday, and Gift Return Tuesday, I have an alternative for you that will make you laugh.

First, I bet you that you have never been as embarrassed as I have been. If you start laughing as you read this story, continue on to get a reward after you’ve finished reading.

The Story:

You think you’ve been embarrassed? Well, I’ve got you beat.

First, it all happened to me on the other side of the planet so I couldn’t go home, turn off the lights and put my head under the pillow.

It happened in Xi’an, China, in an airport the morning I was scheduled to fly to Chongqing to see a panda sanctuary, then board a boat to go down the Yangtze river through the Three Gorges, and then down to Shanghai.

Second, I was traveling with a small group and the Xi’an Airport was huge, so I had nowhere to hide as my embarrassment went on and on and on…

It all started innocently at dinner the night before we were scheduled to fly out of the Xi’an airport the next morning. Our guide addressed the group and informed us that because our plane left so early the next day we all must have our bags packed and outside of our door at 4:30 so they could be picked up and taken to the airport before we went to breakfast.

Everything had to be packed except the clothes we would be wearing the next day and whatever toiletries we required for that morning.

We were told that those toiletries, once used, had to be carried on our person until we landed at Chongqing airport several hours later at which time we could return them to our suitcases.

After dinner that night, we all went up to our rooms, picked out the essential toiletries, which in my case was toothpaste, toothbrush, shampoo, razor, soap, and hairbrush. I also chose my clothes for the next day, which in my case, were one of my endless pairs of khaki pants, a blue long sleeve business shirt, underwear, sox and shoes.

All the rest was packed in the suitcase, which I put outside the door right before I set the alarm and went to bed.

The next morning when my alarm went off, before I showered and shaved, I peeked out the door. My suitcase was gone and on its way to the airport. I looked at the clock and measured the short time I had to get to breakfast.

After my shower, I bundled up my toiletries, put on my blue business shirt and started to pull up my khaki pants, but couldn’t understand why I couldn’t get them on until I realized that the only pair of pants I had to wear were actually those I had mistakenly packed, which unfortunately belonged to my teenage son.

My son has a 32-inch waist. I do not.

I was running out of time. I had to get to breakfast.

I grabbed both sides of the pants so that my fingers gripped the pockets and I hoisted as hard as I could. No progress.

Next, I lay on my back on the bed with my feet extended in the air and bounced on the bed to get maximum leverage, kicked my feet into the air and yanked with all my strength. No progress.

The top of the pants made it to maybe slightly above my crotch. I’m pretty certain I did not get the pants high enough to halfway cover my back end. Nothing.

Next, I tried straddling a chair and forcefully rode my pants like a cowboy rides a horse in order to force the crotch into submission. I then tried jumping up and down to get maximum thrust, lift and torque. Nothing. This was not good!

I had to get to breakfast but I couldn’t leave the room. This was not good at all!

I reassessed my situation.

I still had to put on my shoes and socks. I would have to roll up the bottom of the pants so that I wouldn’t trip over them.

I was able to walk, but only if I could hold the top of my pants up as high as possible, and walk with my knees banging together every time I took a step.

I searched the room for any possible help. I was fortunate to find yesterday’s Chinese newspaper — bright with color — to cover my crotch.

It was a very long and slow elevator ride for every inch of the decent down maybe three floors. I noticed that the Chinese people in Xi’an, at least in this elevator on this particular morning, tended to be very quiet as they tried to find someplace else to look other than at my crotch.

My group at breakfast was less forgiving. They had to stop eating because they couldn’t stop laughing.

Our guide tried to be helpful and encouraged me to wander the airport to find a clothing store, apparently in the hope that I could learn Mandarin instantly and acquire a pair of pants that was twice the size that any self-respecting member of the culture would never wear.

The guide was just trying to be helpful I know, but didn’t seem to understand that I was really, at this point, no longer interested in clothing. I was no longer hoping to fit into the culture.

I was hoping to vanish from the face of the earth.

Everyone in the airport seemed to be walking by and rubbernecking in order to catch sight of whatever everyone else was laughing at.

I was completely hunched over, gripping my newspaper and pants, with my pant legs rolled up above my ankles and, just to add to my unlikely assimilation into the culture, I was wearing my disposable razor, shaving cream, toothbrush, toothpaste and hairbrush bundled up into a boutonniere blooming from my shirt pocket to add to my look.

The Chinese newspaper was fast becoming my most valuable asset since, as it turned out, my seat on the plane was between two meticulously dressed, very frightened Chinese businessmen who apparently feared any eye contact with me, their fellow traveler, for fear that it might prompt me to flash them.

In times like this I try to focus on making my situation into a positive learning experience.

After thinking about my situation for a little while, I concluded there wasn’t a lot to learn so, in the alternative, I thought it might be helpful to try to imagine what could be worse than what was happening to me at this exact moment.

I no longer wonder what it must feel like to wear a miniskirt if you are knock kneed, but that wasn’t bad enough, so I tried to imagine what it was like to wear a miniskirt, knock kneed with high heels.

I made sure that I would be the last person to leave the plane when we landed. in order to give the baggage handlers extra time so when I went to pick up my bag it would be there.

I hid in the airport men’s room for a while. I was afraid I had permanently injured my lower intestines. I was sure I had bruising. I couldn’t really lift or lower my pants now.

Eventually, I built up all my courage and raced through the teeming airport hunched over, with one hand holding the top of my pants and the other gripping my newspaper.

I swooped down on my bag and hauled it into the men’s room, found a stall, opened the suitcase, liberated myself of my son’s pants, and instantly threw them away for no good reason other than I needed to purge them.

A few months ago, I went on a trip with some of that same group that had gone on the China trip. When my story came up, I refused to relive the experience, so they went right ahead and told it anyway. They kept on embellishing the story at my expense.

The trip to China was 10 years ago, and the listeners could not stop laughing. Apparently, it gets better and better.

One person, who I am not sure was even on the China trip, claimed to have seen it all from the back and referred to it as “the morning the moon rose over the Yangtze!”

I must now live in infamy forever.

—

The Reward:

Good for you! You laughed. You are honest because here you are and so you deserve a reward. Now that you’ve laughed you don’t feel quite as bad about not completing your holiday shopping on Black Friday do you?

So here is your reward.

You will be pleased to learn all your remaining shopping can be completed for everybody left on your list, including stocking stuffers!

That story, which you just read, about my “streaking” through China is the very first story in my book, The Older You Get the Shorter Your Stories Should Be, which is now available at The Ivy Bookshop, The Manor Mill, Porter Square Books, or you can order from Bookshop.org (https://bookshop.org/shop/robertrbowiejr) or Amazon.com, where there’s even a Kindle version now! Or you can ask your any book store worldwide to order it using the following ISBN: 978-1628064209.

In addition, this book is perfect for regifting. Buy a copy for yourself. Tell your second recipient that you’ve road tested it because you care so much for them.

Finally, all the stories are short and perfect for your friends and family with short attention spans and they are great for deliberate bathroom reading and, of course, if you buy lots of copies you will make me really happy, too.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Mar 22, 2022 | FringeNYC, General, ONAJE, Operetta, Personal, Plays, Travel

Last Friday afternoon I took the train to New York for the sole purpose of seeing Christian De Gré Cardenas for dinner. The following morning I took the train back home to Baltimore. The only reason for that trip was because he is a friend I just had to see.

It was also a very personal post-Covid-lockdown tip of the hat to celebrate my belief that change is a gift from God.

After my first career as a business trial lawyer I decided I wanted to enter the professional world of theater in New York City, if I could in my late 60s and early 70s.

The only way to get across a chasm so deep was to jump.

Because I was old and no one would read my scripts, I decided I had to take an alternate approach. I decided to use my background as a lawyer so I read all the legal contracts required to be a producer and I took a class in producing theater.

All the young future producers started to ask each other what they wanted to produce. When it came to me I would say: “Nothing. I want you to produce me.”

After I had taken an introductory class at the Commercial Theater Institute in New York, I got a chance to go to the O’Neill Conference in Waterford, Connecticut for an advanced class so I could meet the future big shots.

That trip was a life changer. I hit a gold mine. I met three people within 24 hours who would change my life forever and are my friends to this day: Christian De Gré Cárdenas, Sue Marinello, and Aaron Sanko.

Today I want to talk about Christian and how he has changed my life for the better.

We both got off the northbound train from NYC in Connecticut in the early evening. We were picked up by a van driven by Aaron Sanko, who transferred us to a small motel where we would stay during the conference.

Aaron and Christian knew each other from the New York theater world. I was the old guy in the backseat who didn’t know anything or anybody who had instantly become a groupie.

The next day, Christian and I would be in the same class with Sue Marinello, and we have been bound together with Aaron Sanko ever since. I will talk more about these, my collaborators and friends, as we approach the opening of Mind The Art Entertainment’s (MTAE) upcoming performances, which will be premiering in April, July, and November in New York.

When Christian and I got off the train we looked like two Willy Lomans walking on stage in Death of a Salesman. After we were delivered to the motel and were waiting to register, I decided to talk to Christian and asked him if he would like to go get a drink after we checked in. He never got a chance to answer because the night clerk interrupted to tell us: “Forget about it. Everything is closed.”

Sue Marinello and I sat next to each other at the conference, and she committed to reading my play Onaje. Shortly thereafter, Christian suggested we apply to the upcoming New York Fringe Festival.

After the remarkable success of Onaje, Christian offered me a chance to write Vox Populi, his final operetta in a series based on the seven deadly sins. I immediately accepted and we agreed to meet at a restaurant in Spanish Harlem next to his apartment, where we would sketch out the plot and talk about the tone and temperature of this comedic operetta.

We had the restaurant to ourselves and the waiters brought us food and mescal throughout the afternoon, until the restaurant was set up for the dinner crowd to come in. It was magic.

I went back to Baltimore and went to work at a feverish pace and completed a rhyming rollicking first draft that Christian liked. He invited me to go to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, to marry the music to the words.

Each morning we would get up and go to a little breakfast place that had a wide open garden with a little pond, a beautiful flowered fence, and a balcony with tables for breakfast. We were often alone as we started our day of work.

During breakfast we would go page by page editing the draft, and in the afternoon Christian went to work writing the music while I made changes to the script. Later in the afternoon, Christian would play back the music he had created. In the evening we went to magnificent restaurants in San Miguel and drank more mescal.

Around the plaza and the magnificent church, mariachi bands would sing for the locals, as well as the tourists, and we would walk the streets and listen for music coming from the rooftops. When Christian liked the sound overhead we would enter, go up the stairs, order another drink, and listen until we moved on to the next venue. It was magic.

When we got home at night Christian would go back to work, and in the morning, before we went to breakfast, he would play back what he had composed the night before.

This routine went on for well over a week and somewhere during that time we became brothers in creativity and laughter, and deep friends.

It is amazing how we all step in and out of unique worlds as we change careers or grow older. In my case, as my second career evolved and as I grew older, I stepped into an amazing world of people and experiences that have made me richer and more fortunate.

Unlike any profession I know of, the theater welcomes humanity into an opportunity for friendship in a way somehow the world cannot achieve.

During our dinner in New York last Friday, we were talking about something but I can’t remember what. I just remember Christian looking up straight into my eyes in a moment of surprise and saying: “Do you realize I am exactly half your age?”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jan 30, 2018 | General

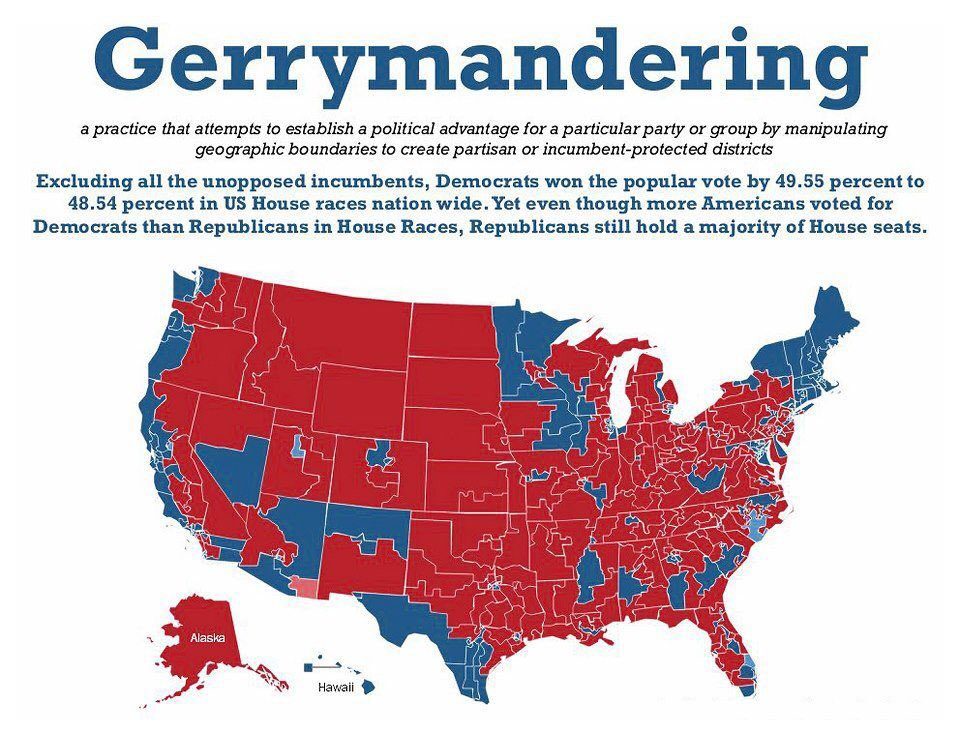

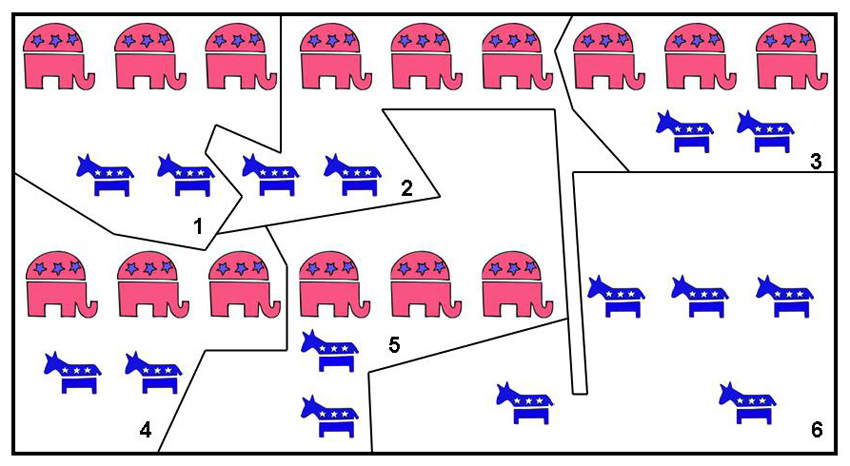

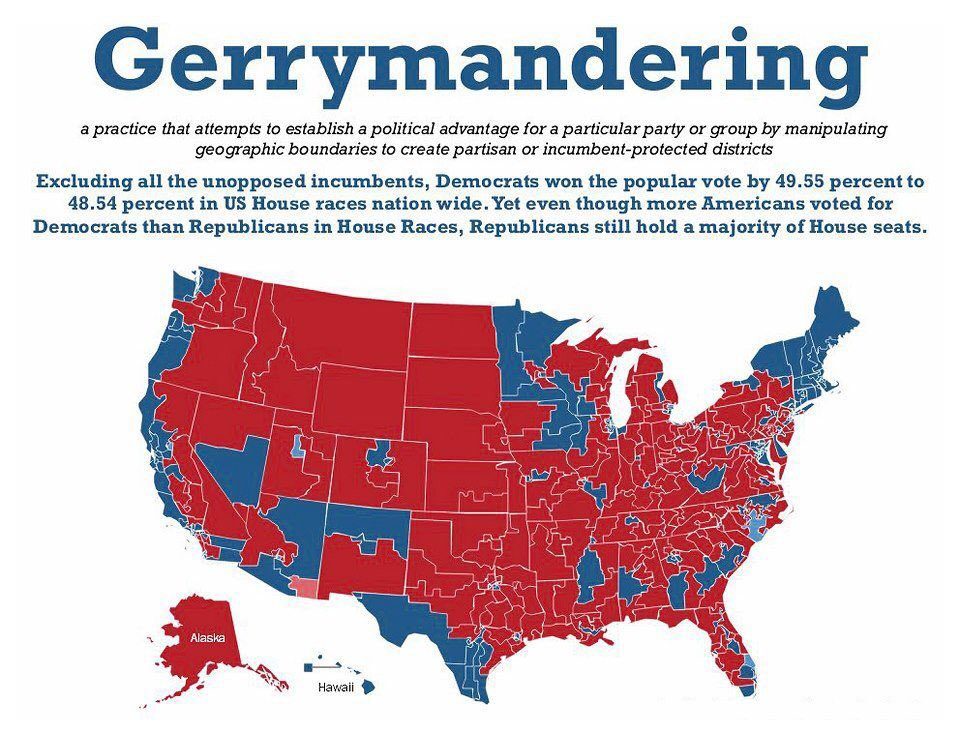

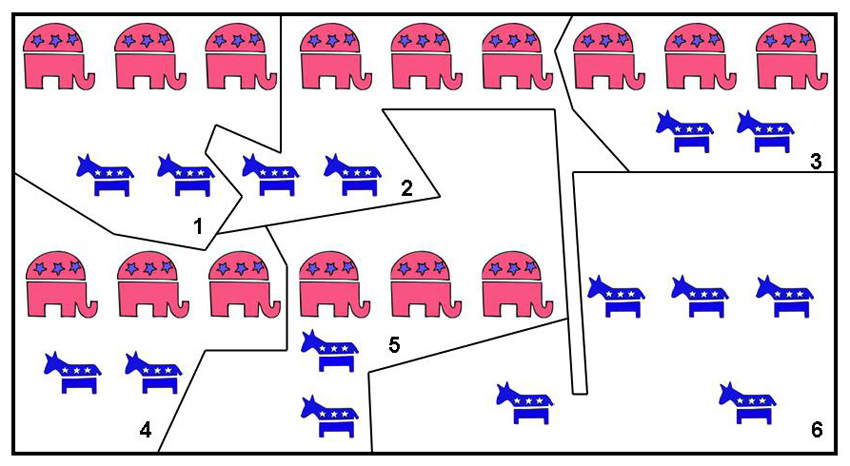

In prior posts, I have talked about how polarization has been caused by gerrymandering and now the judiciary is stepping in to dismantle it.

In North Carolina, on January 9th, Judge James A. Wynn, Jr. struck down the North Carolina congressional district lines. The three-judge panel ruled if state politicians draw district lines for the purpose of protecting their own interest at the expense of the other party, the districts are invalid. Then last week, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overturned gerrymandering, citing the state constitution, and required new districts be drawn by the 2018 midterms.

Most importantly now, the Supreme Court has heard arguments on a gerrymandering case out of Wisconsin and has asked for re-argument of a Maryland case, which will probably be part of an opinion that strikes down gerrymandering nationally.

God bless our state and federal judges. It is long overdue for “we the people” to get the chance to take back our country from our politicians.