by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 18, 2024 | Featured, Humor, Law, People, Personal

As I have said before, I loved representing entrepreneurial business clients because they are crazy.

The little cases are always the funniest and the easiest to tell.

He was a general contractor who built big shopping malls and was always very gruff, extremely overweight and endlessly funny. He, his wife and I, became friends over time and my professional responsibilities merged into our friendship as we got to know each other.

After making a lot of money building shopping centers and stocking them with commercial tenants, he decided to design and build his own mansion. He bought two adjoining lots in a suburban cul-de-sac, and designed what his wife described as “a Las Vegas hotel — not only embarrassing but gauche.”

In his mansion, he determined that he wanted a large indoor fountain, as well as special toilets for his and his wife’s bathrooms. These toilets would protrude from the wall, but have no base onto the floor because he thought that was classier.

He had absolutely no sense of taste.

He battled with the architect who said that these toilets could not withstand his weight and were not classy just because they came out of a wall and didn’t have a base.

She succeeded in vetoing the lavish indoor fountain, but he won the battle in their matching bathrooms with the “extended toilet” from the wall, which had no connection to the floor.

I was his lawyer but we made each other laugh. As I was thinking back on him, I remembered defending him in a lawsuit many years before he built the mansion. He had put a roof on a tenant’s building and the tenant had decided to represent himself because he thought he knew everything about construction and could litigate better than any lawyer.

It was a little non-jury case to be tried in a packed courtroom full of lawyers and clients waiting for their cases to be called. Trying a case in a court at this level is like litigating in a circus tent a head on collision between clown cars — particularly if a defendant or plaintiff comes to represent themselves. The judges at this level have a rotating docket consisting each day of either misdemeanor, criminal, petty civil or traffic court.

I knew the judge socially. He had developed a sense of humor after too many years presiding over these petty cases and traffic court.

The plaintiff in this case argued that the “neoprene” roofing materials had been inadequate, and he was going to be his own expert witness to prove it. The plaintiff was a buffoon who didn’t know what he was talking about. It was a little case that would cost more to try than settle. The client decided to try it “on principle,” which is always a problem. He told me, “I don’t care if you win or lose, just make me laugh.”

I decided to go for broke. After the plaintiff announced that he wanted to be his own expert witness, I decided I would cross examine him on his qualifications before the judge ruled on whether he could be considered as an expert witness on roofing materials.

I asked him if he knew of the latest advancements in “neoprene” roofing materials. He clearly was uncertain but proclaimed he did. I had him hooked. I carefully asked him if he had ever heard of the new “Neofeces” roofing materials.

He said that he had. I spelled it out for him so he could be certain. He cautiously said he was certain.

So now I was crossing him on Neo (new) feces (shit) roofing materials. Clearly you could feel the courtroom saw entertainment in its future.

I asked him if it bothered him professionally that “neo-feces“ was still regrettably not yet odor free. He claimed it did not. I asked him whether he agreed that double-ply toilet paper was considered sufficient for the removal of “neo-feces.” The courtroom rustled as those watching started to follow the tightening of the noose.

After one or two more questions inquiring about the benefits of “neo-Feces,” I paused between the two words and the courtroom started to laugh a little but the witness did not. At this point, the judge stopped me to preserve order in the courtroom and instructed me that I had made my point and had “won the pot with a royal flush.” This was appreciated by all those still waiting to try their cases, as well as the backbench court watchers.

About a month after my client had moved into their new opulent mansion, I got a call from my client’s wife at around 11 o’clock on a weekend night.

She started the conversation by saying that I must come over immediately because she could no longer talk to her husband, who was presently lying on his back on his bathroom floor laughing hysterically.

Apparently, after a night of much beer and football on the super wide screen, he had sat down on his toilet and it had broken off, and he kept slipping and could not stand up because there was water shooting all over the bathroom. I told her I would contact a plumber to turn off the water and then I would be right over.

I asked her, “How bad was it?” She paused on the phone for one second and then just said, “Let’s put it this way, the goddamn toilets he wanted didn’t work, but that’s okay cause he got his goddamn fountain!”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Feb 27, 2024 | Featured, People, Personal, Travel

After Ted Williams, Mohammed Ali and Bobby Orr, since I was a boy, I have been looking for heroes. There have been painfully few. The next generations have not, for me, been fertile ground.

I have just returned from a nine-day trip with a group of 15 friends through Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, and Tennessee. When I came home, I was shocked to learn of Alexie Navalny’s murder in a Russian prison.

I remembered that after Putin tried to kill him once before, he returned to Russia, only to be imprisoned yet again and ultimately murdered. He risked everything for the love of his country, its people and an integrity that is larger than his life. That is this old man’s kind of hero.

It wasn’t my objective but on the trip, I accidentally found the heroes like Navalny that I have been looking for.

For years, I have wanted to follow the “nonviolent” civil rights movement from the death of Emmett Till in 1955 up to when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed in Memphis on Aril 4th, 1968.

Yes, I had seen all the pictures, read the books and knew the dates and places as we all have. This movement started when I was in lower school and compounded until it arguably ended with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. when I graduated from high school in 1968.

It was all familiar to me.

But all the histories and research I had done became like reading the script of a play until I walked onto the stage where it had happened. Then I had no escape. It is different when you are surrounded by it. It is different when you become immersed in it.

The Delta blues surrounded us as we passed the crossroads where Robert Johnson is said to have sold his soul to the devil, then parked down the road near Baptist town to walk near where he had been laid to rest.

Much of the Mississippi Delta, our guide at the front of the bus informed us, is owned by eight families.

For hour after hour, the low flat land passes by, with row after row of cotton plants as far as the eye can see on both sides of the road.

Finally, we left the two-lane road from Jackson, Mississippi and traveled down a dirt road to a big house with five or six little cottages next door to it. These are the houses for the families of the tenant farmers who live there surrounded by their work, earning an annual income of around $8,000 a year — that is, before they paid their rent.

On the bus days later, I tried to better understand the famous 1957 picture of young Elizabeth Eckford as she tried to integrate Little Rock Central High School while screaming white people threatening her 67 years ago. Days later, I met her — now in her 80s — as she sat quietly in front of us and answered questions across from where it had all happened.

She said her parents were determined not to back down and they would not talk about it. She said it had taken her almost 40 years to come to grips with what had happened to her in that one day, and for the remainder of the school year, day after day, as she withstood catcalls and being shoved into lockers as she walked the halls.

That little girl in the picture with the sunglasses on, holding her books alone and determined, gives no evidence of the damage that was done to her, which had stayed with her for so long.

It was much the same with the picture I had seen of the cluster of black men in Memphis as they were all turning and pointing in unison as Martin Luther King, Jr. lay at their feet on the balcony of room 306 of the Lorraine Hotel. The hotel has been turned into a much bigger museum, with a plate glass wall preserving the hotel room that these men had left to talk to friends three stories below. It is now forever frozen with the shades all drawn.

I was not ready for 14-year-old Emmett Till’s final journey down from Chicago to visit family in Mississippi to the candy store where he whistled at a white girl. His two assassins had tracked him down three days later and extracted him at gunpoint from his relative’s house to be beaten beyond recognition and dumped in the river. Days later, he was fished out to be buried back home in Chicago in an open casket.

It all rushed at me hours later, when I found myself in the courtroom where the two men were exonerated in 67 minutes by an all-white jury who said they had a ten-minute Coke break to extend the deliberations. I was sitting in the seat of juror number six, right across from the witness stand where Emmett’s mother had testified in tears.

After I opened the news when I got home, Navalny’s murder drove me back to that trip.

I found heroes in many of the locations we visited. In the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, those heroes were in the records of the hundreds of lynchings, including many who could not be identified.

There are names we all remember, of course. They were committed to their country and to peaceful change despite the daily risk they might be killed. Martin Luther King, Jr., in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, said he could see the promised land, but perhaps he would not be there with them when they entered it. Soon thereafter, he was killed.

Medgar Evers, who was shot from across the street at midnight, had trained his children to run to the bathtub and hide whenever they heard gunshots, because it was the only place they might be safe from a high-powered rifle.

Medgar Evers was killed by a high-powered rifle bullet that went through him, through the front window of his living room, through the wall of his kitchen, and then lodged in the refrigerator.

These people died to advance the cause of freedom. Let’s remember them as we move toward an election that could determine how free we really are.

The night I returned, after I unpacked and turned out the light and set the alarm for an early breakfast, I thought about the people who I had met and the surroundings that had given old history a new life. I went to sleep thinking of those people as little candles where I could warm my hands, little flickering lights burning in the dark.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 22, 2023 | Featured, People, Personal

Many of us in our joyous misspent youth, particularly in our teenage years, enjoyed the undisciplined fun of our juvenile hubris.

Hubris is an ancient Greek word that describes excessive exuberance, confidence, or pride, which can often bring about one’s downfall.

The art of teaching teenagers during the hubris years requires a middle path, somewhere between crushing the hubris and leaving it untethered. This middle path requires the difficult task of helping a student to channel hubris to promote individuality and personal growth, because this youthful burst of enthusiasm often can be the first sign of what a young person’s real interests really are.

Think of the people you know who discover that they hate their careers in midlife and go in an entirely different direction or, worse, don’t.

My experience is that many of these people were not educated to question and challenge their conclusions. Rather, they were educated to take good notes and vomit it all back on the final exam to be rewarded with a great grade, and then passively step into careers in which they were never really interested.

Whitney Haley, our drama teacher at the Cambridge School of Weston, was a master of the middle path. He marshaled his resources and directed us with surgical, gentle humor.

Whitney was an aging, portly diabetic, who had long ago retired from a career in the silent movies. He did everything with an intentional dramatic flair. He pronounced his name with one hand dancing in the air as Whit-Née (brief dramatic pause) Hay-Lée (and then wait for our response). He herded us with humor rather than a cattle prod. Everybody loved Whitney Haley!

In our high school play, I was cast in the role of John Hale, the strict Puritan minister, in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. Before opening night, we all applied our own make up, which was approved by Whitney before we went on stage.

I came to the conclusion, as I was putting on makeup for the first time ever, that John Hale was actually “tall, dark, and handsome.” I decided he had to be Movie Star Handsome.

Whitney walked by and noticed that I was becoming darker and darker. With his customary dramatic flare and his best stage whisper, he intoned: “Perhaps my memory has failed me. Isn’t this a play about a witch-hunt, which did not happen to take place on the beach.”

The dressing room broke into laughter but it was not at me, it was how Whitney delivered his edict. I had not been shamed. I had just been encouraged to take a second look in the mirror, and become educated as to my “hubris.”

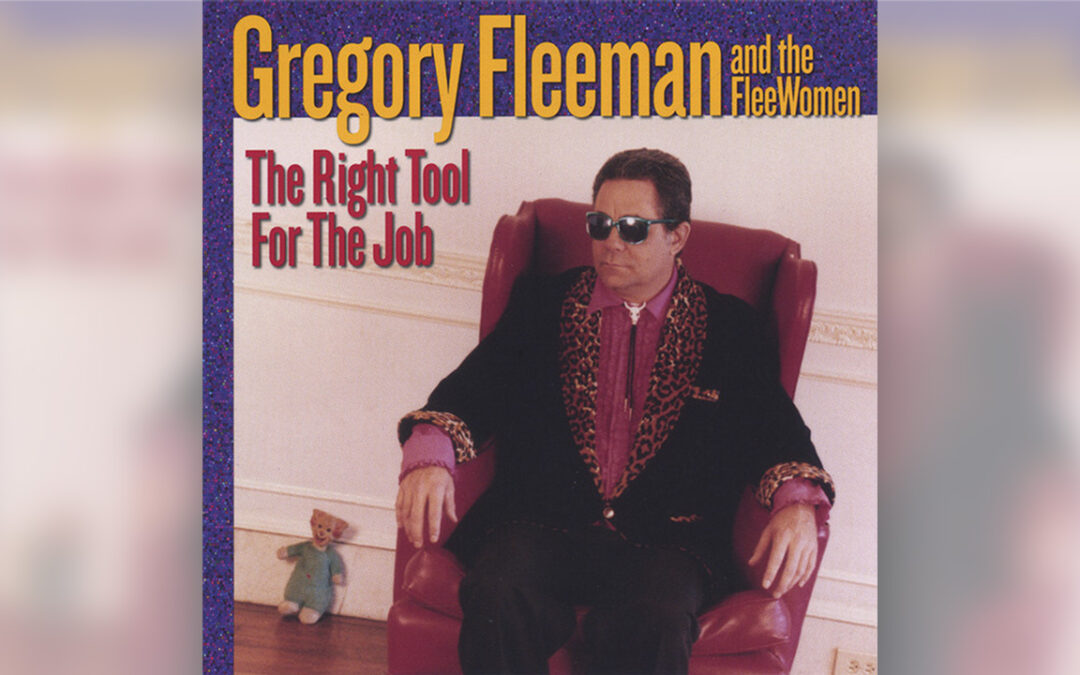

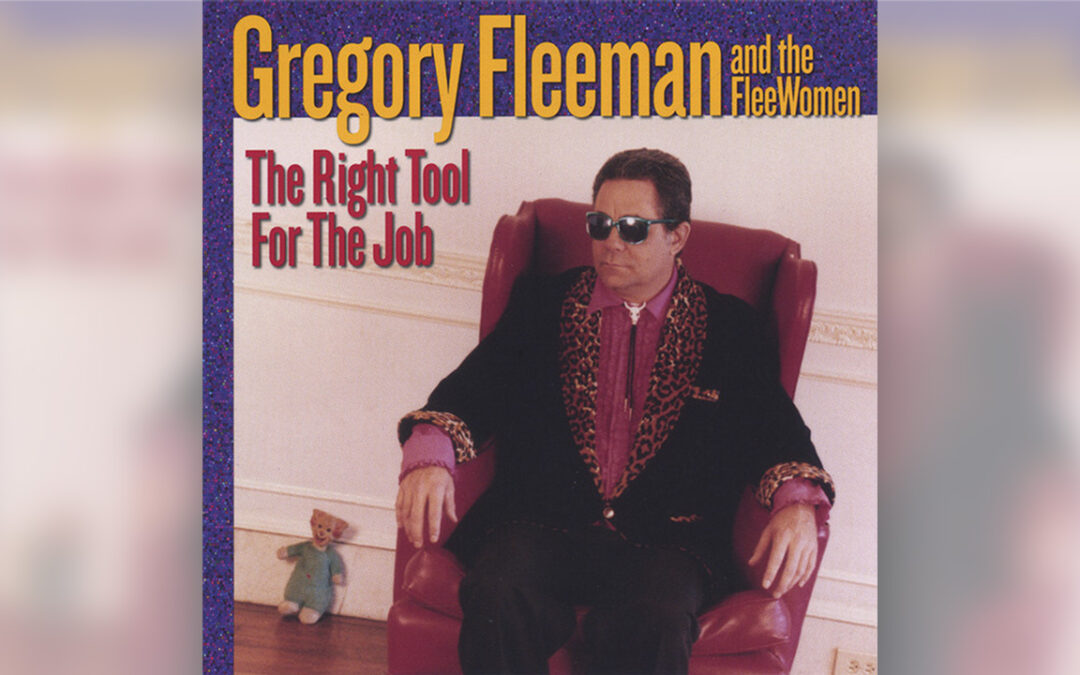

Unquestionably, Whitney Haley‘s favorite student was Greg Fleeman, who could not stop himself from making people laugh. He literally could not help himself. He was constantly funny.

When Greg would bring his chaos to Whitney’s classroom and inadvertently shut down the class, Whitney, with his perfect timing, would stop the class, go into his pocket, and offer him a handful of change: “Greg-or-ee. Would you mind if I interrupted you briefly and trouble you to step out of the room, travel down the hall to the candy machine, and acquire a Milky Way candy bar for me, which I will gladly give you as a reward at the end of this class if you will allow me to continue to pursue my chosen profession?“

Whitney, with his perfect timing, would regain order to his classroom with humor and without injury or shame.

One Christmas vacation, Greg invited me back to visit his family in Miami. His father had been a developer of real estate on Miami Beach, which had made him very wealthy, but Greg, who I believe was his youngest son, had absolutely no interest in taking over his father’s business. Greg’s family had surrendered their son to the Cambridge School Of Weston to let him be who he was, despite their ambitions for him.

The first night I was invited to a somewhat formal evening meal. Mr. Fleeman sat at the head of the table. Greg never stopped talking, and his father never stopped laughing uncontrollably.

Greg went on to become a very original and eccentric rock musician. He also became the apple of his father‘s eye, the family business be damned. Greg was much too eccentric to be appreciated by the audience of his day, but he was invited regularly backstage by those more famous than he.

I saw him perform with his band, Greg Fleeman & the FleeWomen, at a small venue in Greenwich Village. He had a small but very loyal following. He was like a standup comedian with an amazing voice. He was always Mr. hubris. but with Whitney whispering in his ear.

Greg Fleeman was far too original to even be considered by schools that granted good grades to those who were able to take notes and recite back what the teachers had said rather than question everything, which is what CSW had taught us to do.

Many of the people who I went to school with describe their experience at the Cambridge School Of Weston as “life-saving.” So it was, not only for Greg Fleeman, but also Whitney Haley and me.

Whitney is long since gone and Greg Fleeman died last year, but he left a CD, “The Right Tool for the Job,” which I go back to again and again, just because it holds all of his irreverence, both in his lyrics and his orchestration. My favorite tracks are “My Ex Wife” and “Skin Tango.”

You can listen to it on YouTube: https://youtu.be/wjqnSOl41Ac.

He was original, and became himself because everybody else was taken.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 15, 2023 | Featured, People, Personal

Back when I was growing up, I was taught two different definitions of success: the so-called “self-made man,” and the person who creates community. For me, two very different people have proved this point.

One was a client of mine in the early years of the law firm I’d created as a sole practitioner in 1990. He was a businessman from rural, hardscrabble Pennsylvania, who had moved to Maryland when he was young and made a lot of money, developing lots for home construction in the Baltimore suburbs. With his success, he built a grand house, lavished gifts upon his wife and three boys and, for himself, he bought a limousine and hired a driver.

The businessman defined himself as a “self-made man.”

The other was my soccer coach at the Cambridge School of Weston, who built a high school sports team at a progressive school in the late 1960s. He was soft-spoken, had an easy smile and natural authority.

Both were entrepreneurial but their styles couldn’t have been more different.

Cambridge School of Weston was a little progressive school outside of Boston. For every other school, the preferred fall sport was football. CSW offered either soccer or rugby, I think because the equipment was cheaper and both of these sports served the character of the school better than football.

Another difference was our mascot. The schools we played against had lions and tigers, bulldogs and bears. We had a gryphon, and our school newspaper was called The Gryphon’s Eye. For half my first year, I didn’t know what a gryphon was. When I looked it up, I found out it was a ”fabulous beast with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion.”

All the other schools had fierce animals, and we had a myth as a mascot, which seemed fitting.

This little progressive school changed my life. It bucked the system and the traditional trends of the times. It taught a Socratic education. It encouraged us to question everything.

Anyway, our soccer coach was typical for this school because he taught us to challenge traditional authority and conventual behavior.

At this time, the strategy of high school soccer was to kick the ball as far as you possibly could down to the other end of the field and then try to score before the other team’s defense would kick the ball back up the field and then try to score using the exact same logic and conventions.

This strategy for the long kick game was dependent on speed and power. It required constant, repeated substitutions of the entire offensive, midfield, and defensive players whenever there was a whistle or break in the action, before the players became exhausted.

Finley was outside of the box from the start. He had to be. We only had about 15 players to fill 11 positions and, to make matters worse, we were ragtag free spirits who sang and played guitar during free periods and attended school in sandals.

Discipline, like running laps, took some reprogramming.

Finley built his future team by turning disadvantage into advantage. He told us that we would not substitute any of our 11 players unless there was an injury serious enough to cause removal. He knew our fear of exercise was real.

He informed us that we would have to get in shape, but he would not run us the way the other teams were trained. He had a plan. He informed us that anyone who kicked a ball that went over the height of the knee of the teammate we were passing to would have to instantly do a lap.

Findley built an offense out triangles. All we had to do is maintain control of the ball by passing, no higher than the knee of the recipient, and that person did the same thing to another teammate to complete the triangle. Once that was established, we were in control of the ball until we could take a shot on the opposing goaltender. If we could perfect this style, we could run the other team ragged, no matter how many substitutions they made.

Basically, it was pinball, but we bonded around it, pretty much mastered it, and my recollection is that we lost only one game against huge high schools, who replaced lines and kicked the ball down the field until we got the ball and again controlled it and scored.

We never were as big or athletic as the other teams. We were in shape, but we never ran like the other teams did. We didn’t have to. Because I was the laziest person on the team, I was the goalie. I think I only was scored on once the entire season not because I was any good but because I never saw the ball.

Findley was admired as a genius but not because he was a self-made man.

The client I represented who saw himself as a self-made man believed the soul of American capitalism was dog-eat-dog. He would, where possible, never pay his bills and, before I represented him, his prior lawyer had set up corporations within corporations that had no assets so that when a lawsuit was filed against him, there would be no money to pay the opponents if they won.

Eventually, no one would do business with him.

He lavished gifts on all of his children because it was important that they loved him, but he refused them a college education because he had none and he did not want them to be superior to him. Two of his three boys became dependent on drugs and were homeless for a period of time.

In contrast, Finley built a team that was a small but cohesive. He forced us to get out of ourselves and into supporting each other and our goal, which was to patiently beat better teams.

I’ve always believed that you are what you do, not what you say. Findley was way ahead of his time in the world of American soccer. The passing game that he taught us had been used before in Europe but he adopted it to fit his needs.

I learned from his wonderful madness.

My client’s wife called me moments after her husband died. He had been waiting for a heart transplant and was receiving daily transfusions to stay alive. When she called me, she was in tears. She said his last words were, “I can’t see! Why can’t I see? I’m not ready to die yet. I’m not ready to die.”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jul 25, 2023 | Featured, People, Personal, Travel

Years ago, I met a boy who never once told me the truth but had the heart of a saint.

Back in August 1968, outside of Cheyenne, Wyoming, I was hitchhiking east when a state trooper pulled up next to me. He told me that he was going down the highway for 15 minutes, then turning around, and if I wasn’t gone by the time he came back he was going to lock me up in Cheyenne “until I got a court date.“

This was serious.

As the officer’s taillights disappeared down Interstate 80, I turned around to face the empty road and stuck out my thumb.

I needed a miracle.

As the first car approached, I knelt by the side of the roadway with my hands pressed together simulating prayer.

That car, an old white Ford convertible, was driven by a boy who appeared to be in his mid-20s. He wore a huge cowboy hat, and rhinestones from his shirt collar to his new boots. The boy pulled over and waved for me to get in.

As I thanked him and started to explain my predicament, he laughed and waved off any further conversation. He told me not to worry because he would be driving all night to see his father in Fort Dodge, Iowa.

First car? This guy? It was a miracle… but it gets better.

Next, he asked me if I was hungry. I laughed and nodded yes, and he reached under his seat to hand me a can of peaches, a can opener, and a plastic fork.

He was clearly showing off. You could tell by the grand gestures of his performance and his broad grin. He was having fun.

After I finished the peaches and drained the can of its last sweet syrup, I settled into the ride as he started to talk. He told me that he had been a foreman for the last several years at a ranch, and the night before in Reno, he had girls in the front and back seats of this very car because he had won money in the slots.

As we drove deeper into the night he told me that before he had been a cowboy he had been a soldier of fortune, and had parachuted into Nicaragua as an agent for the CIA.

His stories were endless and detailed, full of life and love and compassion for those he had worked with, and for the women he had been fortunate to love, as well as those who had broken his heart but had been kind enough to have loved him back for a while.

He was a natural storyteller and the more we relaxed together and talked, the more I liked him for his joy.

Slightly before dawn, when we turned off the Interstate and headed up toward Fort Dodge, he offered a surprising apology: “My old man never amounted to much. He was a postal worker. He drank himself out of the job but he’s always been there for me. He is sick now. I never knew my mom. She left him, but my father, he always has been there for me.”

As the light brought color into the outskirts of Fort Dodge, we turned onto a street of freestanding houses in an empty neighborhood with untended lawns, litter on the streets, and an occasional abandoned car.

The door to his father’s house was open and the window next to the front door was broken. As we entered, I looked to the right. There was a kitchen with a table and two chairs. To the left was a living room with no furniture. Straight ahead was a staircase with a simple railing and some of the slats missing, which led to a second floor. There were crushed beer cans on the floor and heaping ashtrays on the countertop by the sink.

The boy headed upstairs to go wake up his father. Moments later, there was some heavy coughing from upstairs and muffled voices. There was the sound of crying, raised voices, but also laughter.

After several minutes, an old man slowly navigated the steps and stopped to catch his breath when he reach the bottom step.

The old man apologized for the state of the house and immediately went the the old ice box. He got three beers and proceeded to handed them out. Apparently, these were breakfast beers.

Oddly, the whole house seemed to be filled with love and I felt welcome.

As the sun came up, the two were lost in each other’s company, and so I timidly asked if I might be allowed to take a shower since I had been on the road for several days. The old man responded “Sure!” He lit a cigarette and pointed at a wash tub leaning against the kitchen wall. He told me to fill it with hot water from the sink and handed me a big jug of dish washing detergent.

I felt that I could not refuse the kindness. I filled the tub with warm water and detergent, stripped naked, and started to take a bath. The boy and his father paid no attention as they laughed and talked and smoked.

Almost immediately the police arrived, knocked on the unlocked door, then entered. They arrested the boy, put him in handcuffs and shoved him through the door toward the squad car out front. The old man burst into tears. With a beer still in hand, he begged them to release his son as the officers pushed the boy down the walkway and put him in the back seat. The officers never spoke to the pleading old man except to say. ”If you touch me, I will take you in too.”

During the entire arrest the police paid no attention to me at all as I sat naked in a wash tub and tried to surround myself with heaps of bubbles.

When the old man returned from the street, he explained through his tears that a week ago his son had finally been released on parole from a Kansas prison. He had been thrown out of school several years before, and had been convicted as an adult for smoking marijuana near the school yard. He wasn’t a bad kid. Just a free spirit from the wrong side of town.

His father had gotten the old convertible for him and told him he could never outlive his past in Kansas. He told him to go west and “disappear” and never come back again.

The boy had initially agreed, but he had told his father upstairs that he had become homesick for the old man and he was afraid he would die and the boy would never see his father again.

Everything the boy had told me for the last 12 hours riding through the night was a lie, and also a life he would never have the chance to live.

The old man said he and his son had talked every week during the boy’s incarceration and the boy had told him he read all the books and magazines and newspapers he could find in prison.

After the old man had fortified his courage with a few more beers, he marched out the front door and headed toward the police station, which was apparently several miles away.

Alone in the empty house, I dried off with paper towels, slept a little on the living room floor, then in mid afternoon, hitchhiked to a postal delivery hub. I got a ride from a man driving a Mail truck headed east toward Chicago. He told me he’d gotten married the day before, and had been up all night. When the driver started to hallucinate dogs running across the Interstate, I volunteered to drive so he could sleep. We switched seats without stopping.

As dawn arrived, with the sleeping driver by my side, I thought about the boy and wondered why he would lie to me all night about a life he never lived, then take me to his home where his lies surely would be revealed.

Maybe it was to show he had a kind heart and a moral code, despite his life. Maybe he just gave up and didn’t care. As the sun was coming up in the cab of that mail truck, I realized that I had never asked his name, nor had he asked me mine.

Years later, it occurred to me that no matter how hard I might try, I would never be able find that boy again.

I still think of him often. He was one of the kindest people I have ever met. He has appeared in my poems and plays as a reminder that we really are what we do, not what we say.