by Robert Bowie, Jr. | May 20, 2025 | Featured, Personal, Travel

When Susan and I flew to Paris again this year for three weeks this spring, I had planned to watch the Bob Dylan movie, “A Complete Unknown” on the flight that night, but I was too tired so I slept instead.

Paris was warming to its spring as we landed at Charles De Gaul airport and traveled into the heart of Paris to a beautiful flat with its view of the Seine from its fifth floor living room and bedroom windows on the Île Saint-Louis.

The six hour difference in the time between the East Coast of the United States and Paris delayed the news reports that poured into my cell phone at three in the afternoon Paris time as America woke up and went to work.

The distance and the time change diminished my obsession to keep up with America’s politics, but nothing could uncouple it from my daily concerns.

Over our three weeks, Susan and I committed to walk the city, but for longer trips to Montmartre or the outskirts of Paris to the Louis Vuitton Museum to see the huge new David Hockney exhibit, we took the Metro.

Each evening, we would go to one of the little restaurants on Île Saint-Louis and then climb the stairs or take the little elevator to the flat to read the news before bed.

Last year. we had taken three days off from Paris to go to the LaVar Valley to stay in a beautiful Château and visit the region’s medieval history. This year, we went to Normandy and, as I observed the beaches and cliffs, and finally the dramatic American cemetery, the pride I’ve always felt for America rekindled with my respect.

On the morning that we flew back in mid May, Paris was in full bloom as we got on the plane to fly into the upcoming day on our return to the United States.

I again committed to watch the Bob Dylan movie on our way home.

Even though it had been out for some time, I still had not seen it, but I knew enough from the reviews that it was about the transition from Dylan’s early folk years to the electric folk rock that Dylan made in 1965.

In the fall of 1965, I had started my first year at the Cambridge School of Weston, a progressive high school that knew something about learning disorders and thus was unlike the boarding schools and summer schools I had attended previously.

It was my second try at 11th grade. My new school was so very different in so many ways, but as my classmates wore sandals and blue jeans and played guitars out on the quad or went off to the ceramic studio and the wide range of classes offered, I attended my classes in a sport jacket, but eventually gave up on the tie.

I believed I was in transition to a better place and I believed that from the start. I was hoping that repeating the 11th grade would rekindle my love of learning in a new environment with a fresh start.

Within weeks of my first day, a sign-up sheet went up in the dining room, which offered tickets and a bus ride provided by the school to see Bob Dylan play in a Boston theater.

I signed up with about 15 of my fellow students and we got on a little bus to go down to the theater.

When we got to the venue in downtown Boston, we were told that it had been sold out almost immediately and, though we had paid for our tickets, no seats had been assigned for us.

The theater instantly took action and placed folding chairs in a semicircle on stage directly behind Bob Dylan.

The first half of the performance was all Bob Dylan singing his folk songs in front of an adoring audience with us directly behind him.

When the audience returned to their seats for the second half of the program, however, a rock ’n’ roll band was now set up to back up Dylan. We pushed our seats back further to accommodate the instruments and cables.

When Dylan entered, he was met with catcalls. I could not believe what was happening in front of me. I sat, self-conscious and a little bit frightened, as Dylan faced the catcalling audience.

Dylan played the first few songs with the electrical back up in the midst of the continuing catcalls.

Somewhere in the middle of one of those songs, a very loud voice broke through and yelled something like, “You sold out!”

Dylan stopped the performance. After a very awkward moment, the silence was broken by Dylan’s voice over the microphone:

“I don’t believe you!” he said, and there was a smattering of applause as he signaled to start the song again, resuming the concert.

As the movie portrayed the transition at the Newport Folk Festival from folk to folk rock, Dylan spoke those same lines to that hostile audience and I returned momentarily to being a teenager on the back of that stage. But I was proud to be there rather than surprised and frightened by the event.

As we landed at Dulles Airport in Washington DC, and returned to our political world, I felt reborn and re-nourished by the experience.

I had this very odd feeling that these juxtapositions had reawakened me to the messy but resilient democracy in which I have been fortunate to have lived and prospered.

Somehow, America, through its history, has been endlessly capable of being reborn, newly appreciative of what the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution have provided for each generation.

Shortly thereafter, I laughed when the news reported that Harvard University had discovered in its archives an original copy of the Magna Carta, which had been presumed to be a copy, purchased in England for less than $30 after the Second World War. It turned out to be the thing itself.

It was a great trip to Paris, which taught me yet again how much I love this country.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 16, 2025 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Politics, Travel

I’m not really worried about Trump taking over Harvard, so Susan and I are going to Paris this Saturday for a couple of weeks.

Why is everybody so upset? It seems like all the commentators have completely overlooked Trump’s leadership skills when he ran Trump University.

Trump has been very vocal about his business acumen and, by his own account, he ran the university brilliantly for the five years before its bankruptcy.

There was some unsubstantiated criticism about gold toilet seats, but he claimed he was always very hands-on and was good at keeping the overhead low.

For example, despite its name, Trump University was never an accredited university or college. It did not confer college credit, grant degrees, or grade its students.

Think about the savings on the cost of paper.

In contrast, the data from the 2023–24 academic year, 72% of Harvard University’s first-time, full-time undergraduates received financial aid. In the alternative, Trump University was apparently so popular, it never needed to offer scholarships. And Trump has already said that he wants to get rid of Harvard’s nonprofit status.

Really! So where is the art of the deal?

Harvard is not effectively selling its product! No. Harvard has been giving it away for free.

What is also great is that Trump has the experience to navigate these litigious times. In 2011, Trump University became the subject of an inquiry by the New York Attorney General’s office for illegal business practices, which resulted in a lawsuit filed in August, 2013. It was also the subject of two class actions in federal court. The lawsuits centered on allegations that Trump University defrauded its students by using misleading marketing practices and engaging in aggressive sales tactics.

Of course!

Everyone knows that Trump is a marketing genius! Okay, let’s get down to what Trump‘s real motives may be.

Both schools have one thing in common.

Neither school has a mascot.

Everybody knows that Trump is a master marketer. I think the hidden agenda will be that Trump will insist that Harvard finally adopt a formal mascot, befitting our country’s white Christian heritage: a Pilgrim, of course!

But even more importantly, this way he can get rid of that out of date logo “Veritas” and change it to “If you piss off a pilgrim, you’ll get yourself a witch trial.” Then he can raise money at halftime with a raffle where the winner gets whisked away for a lifetime in El Salvador.

Anyway, just like last year, Susan and I will be sending back Parisian commentary and pictures to celebrate our spring time and hopefully brighten yours. À bientôt!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Mar 18, 2025 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Travel

In Buddhism, there are instances of instant enlightenment brought by shock or surprise.

(I feel it is okay for me to comment on Buddhism and its wisdom as long as I admit to you that I know nothing about it.)

Nonetheless, I offer an example:

There are instances where a monk will slap a student of Buddhism to surprise them or shock them into enlightenment.

I have always worried about this experience of receiving shock and resultant enlightenment ever since I may have accidentally shocked some Buddhists out of their enlightenment.

It all occurred in the second floor men’s room of The Charles Hotel in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Many years ago, I took a morning plane to Boston dressed travel casual, with my blue suit, white shirt, tie, black socks and black lace-up shoes in my suitcase. I was to attend important meetings that afternoon in Cambridge.

When I got to The Charles Hotel in the early afternoon, I was informed my room was not ready. I had nowhere to change into my suit.

I was told the delay was because the Dalai Lama and his large entourage were staying at the hotel. The Dalai Lama was there to plant a tree in Harvard Yard with the Harvard president and then scheduled to go off to Foxborough to give a message to the masses in the football stadium. Apparently, the hotel was behind schedule because of these new guests.

Since I couldn’t get into my room, my only alternative was to go to the second floor men’s room of The Charles Hotel with my suitcase and haul it into the handicap stall of the public men’s room, where I would have enough room to change.

I put the suitcase on the toilet seat and began to disrobe and change into my business attire.

I hung my suit on the back of the stall door, unpacked my black shoes and pulled out my dark socks, and was starting to put on the white shirt when I heard the unexpected sound of chattering female voices exploding into the men’s room.

There seemed to be a great urgency and effort to bring in two people who were in wheelchairs. One, a very old woman and the other, a very old man. These voices were not in English.

I stood there, stunned with my suit pants in one hand and a black sock in the other and stood listening. It sounded like a kitchen in a busy restaurant.

I tried to peek through the crack in the door, but only saw a flurry of female activity. All I could make out was at least one person, perhaps more, had an urgent need to go to the bathroom.

I waited patiently with my sock and my pants, but nobody was leaving. It was as if everybody, male or female, had to urgently go to the bathroom.

I waited for nearly 10 minutes, but I was late for my meetings, so I had to make a decision about what to do.

I quickly dressed and repacked my suitcase. I decided to open the door and just march straight through this mob of people.

Given the circumstances, this was a very rude thing for me to do, but given the fact that I was in a men’s room, I felt entitled.

With my suitcase in one hand, I pushed open the door and confronted the group.

Instantly, there was stunned silence and, as if my mind were a flash camera, I had a mental picture of as many as 20 colorfully-dressed people staring at me with their mouths open.

There were people staring as they stopped washing their hands. There were people staring as they stopped midway through entering or exiting a stall. Everything was frozen.

Then there was a collective gasp. Not a shriek or anything, just a gasp. I tried to pretend I was invisible as I barreled toward the exit with a sea of bright colors parting on both sides.

I may have caused significant damage. Or, possibly, I shocked some of the entourage into a different vision of enlightenment.

First, it was clearly an emergency of some sort. Somebody had to really go to the bathroom badly and I fear it was an old person.

Second, these were elderly people in wheelchairs and I am not handicapped but I was in a handicap bathroom.

Third, and finally, I consider myself a very sensitive person but even if I had no empathy at all, one must consider reincarnation in all of this.

I offer no excuses. I think there may have been damage done to me, as well. I’m certain my karma is permanently shot. If there is reincarnation, I shudder to think what I will come back as.

So I’ve confessed it. I will also confess that I’m a believer in the “butterfly effect,” which is that every action causes a ripple across the universe.

If anything good comes from this, it is simply that I can warn you to be careful if you run into a similar situation.

You never know when a cosmic event will hit you.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Dec 3, 2024 | Featured, General, Personal, Shorter Stories Book, Travel

If you’re tired of Black Friday, Small Business Saturday, Cyber Monday, and Gift Return Tuesday, I have an alternative for you that will make you laugh.

First, I bet you that you have never been as embarrassed as I have been. If you start laughing as you read this story, continue on to get a reward after you’ve finished reading.

The Story:

You think you’ve been embarrassed? Well, I’ve got you beat.

First, it all happened to me on the other side of the planet so I couldn’t go home, turn off the lights and put my head under the pillow.

It happened in Xi’an, China, in an airport the morning I was scheduled to fly to Chongqing to see a panda sanctuary, then board a boat to go down the Yangtze river through the Three Gorges, and then down to Shanghai.

Second, I was traveling with a small group and the Xi’an Airport was huge, so I had nowhere to hide as my embarrassment went on and on and on…

It all started innocently at dinner the night before we were scheduled to fly out of the Xi’an airport the next morning. Our guide addressed the group and informed us that because our plane left so early the next day we all must have our bags packed and outside of our door at 4:30 so they could be picked up and taken to the airport before we went to breakfast.

Everything had to be packed except the clothes we would be wearing the next day and whatever toiletries we required for that morning.

We were told that those toiletries, once used, had to be carried on our person until we landed at Chongqing airport several hours later at which time we could return them to our suitcases.

After dinner that night, we all went up to our rooms, picked out the essential toiletries, which in my case was toothpaste, toothbrush, shampoo, razor, soap, and hairbrush. I also chose my clothes for the next day, which in my case, were one of my endless pairs of khaki pants, a blue long sleeve business shirt, underwear, sox and shoes.

All the rest was packed in the suitcase, which I put outside the door right before I set the alarm and went to bed.

The next morning when my alarm went off, before I showered and shaved, I peeked out the door. My suitcase was gone and on its way to the airport. I looked at the clock and measured the short time I had to get to breakfast.

After my shower, I bundled up my toiletries, put on my blue business shirt and started to pull up my khaki pants, but couldn’t understand why I couldn’t get them on until I realized that the only pair of pants I had to wear were actually those I had mistakenly packed, which unfortunately belonged to my teenage son.

My son has a 32-inch waist. I do not.

I was running out of time. I had to get to breakfast.

I grabbed both sides of the pants so that my fingers gripped the pockets and I hoisted as hard as I could. No progress.

Next, I lay on my back on the bed with my feet extended in the air and bounced on the bed to get maximum leverage, kicked my feet into the air and yanked with all my strength. No progress.

The top of the pants made it to maybe slightly above my crotch. I’m pretty certain I did not get the pants high enough to halfway cover my back end. Nothing.

Next, I tried straddling a chair and forcefully rode my pants like a cowboy rides a horse in order to force the crotch into submission. I then tried jumping up and down to get maximum thrust, lift and torque. Nothing. This was not good!

I had to get to breakfast but I couldn’t leave the room. This was not good at all!

I reassessed my situation.

I still had to put on my shoes and socks. I would have to roll up the bottom of the pants so that I wouldn’t trip over them.

I was able to walk, but only if I could hold the top of my pants up as high as possible, and walk with my knees banging together every time I took a step.

I searched the room for any possible help. I was fortunate to find yesterday’s Chinese newspaper — bright with color — to cover my crotch.

It was a very long and slow elevator ride for every inch of the decent down maybe three floors. I noticed that the Chinese people in Xi’an, at least in this elevator on this particular morning, tended to be very quiet as they tried to find someplace else to look other than at my crotch.

My group at breakfast was less forgiving. They had to stop eating because they couldn’t stop laughing.

Our guide tried to be helpful and encouraged me to wander the airport to find a clothing store, apparently in the hope that I could learn Mandarin instantly and acquire a pair of pants that was twice the size that any self-respecting member of the culture would never wear.

The guide was just trying to be helpful I know, but didn’t seem to understand that I was really, at this point, no longer interested in clothing. I was no longer hoping to fit into the culture.

I was hoping to vanish from the face of the earth.

Everyone in the airport seemed to be walking by and rubbernecking in order to catch sight of whatever everyone else was laughing at.

I was completely hunched over, gripping my newspaper and pants, with my pant legs rolled up above my ankles and, just to add to my unlikely assimilation into the culture, I was wearing my disposable razor, shaving cream, toothbrush, toothpaste and hairbrush bundled up into a boutonniere blooming from my shirt pocket to add to my look.

The Chinese newspaper was fast becoming my most valuable asset since, as it turned out, my seat on the plane was between two meticulously dressed, very frightened Chinese businessmen who apparently feared any eye contact with me, their fellow traveler, for fear that it might prompt me to flash them.

In times like this I try to focus on making my situation into a positive learning experience.

After thinking about my situation for a little while, I concluded there wasn’t a lot to learn so, in the alternative, I thought it might be helpful to try to imagine what could be worse than what was happening to me at this exact moment.

I no longer wonder what it must feel like to wear a miniskirt if you are knock kneed, but that wasn’t bad enough, so I tried to imagine what it was like to wear a miniskirt, knock kneed with high heels.

I made sure that I would be the last person to leave the plane when we landed. in order to give the baggage handlers extra time so when I went to pick up my bag it would be there.

I hid in the airport men’s room for a while. I was afraid I had permanently injured my lower intestines. I was sure I had bruising. I couldn’t really lift or lower my pants now.

Eventually, I built up all my courage and raced through the teeming airport hunched over, with one hand holding the top of my pants and the other gripping my newspaper.

I swooped down on my bag and hauled it into the men’s room, found a stall, opened the suitcase, liberated myself of my son’s pants, and instantly threw them away for no good reason other than I needed to purge them.

A few months ago, I went on a trip with some of that same group that had gone on the China trip. When my story came up, I refused to relive the experience, so they went right ahead and told it anyway. They kept on embellishing the story at my expense.

The trip to China was 10 years ago, and the listeners could not stop laughing. Apparently, it gets better and better.

One person, who I am not sure was even on the China trip, claimed to have seen it all from the back and referred to it as “the morning the moon rose over the Yangtze!”

I must now live in infamy forever.

—

The Reward:

Good for you! You laughed. You are honest because here you are and so you deserve a reward. Now that you’ve laughed you don’t feel quite as bad about not completing your holiday shopping on Black Friday do you?

So here is your reward.

You will be pleased to learn all your remaining shopping can be completed for everybody left on your list, including stocking stuffers!

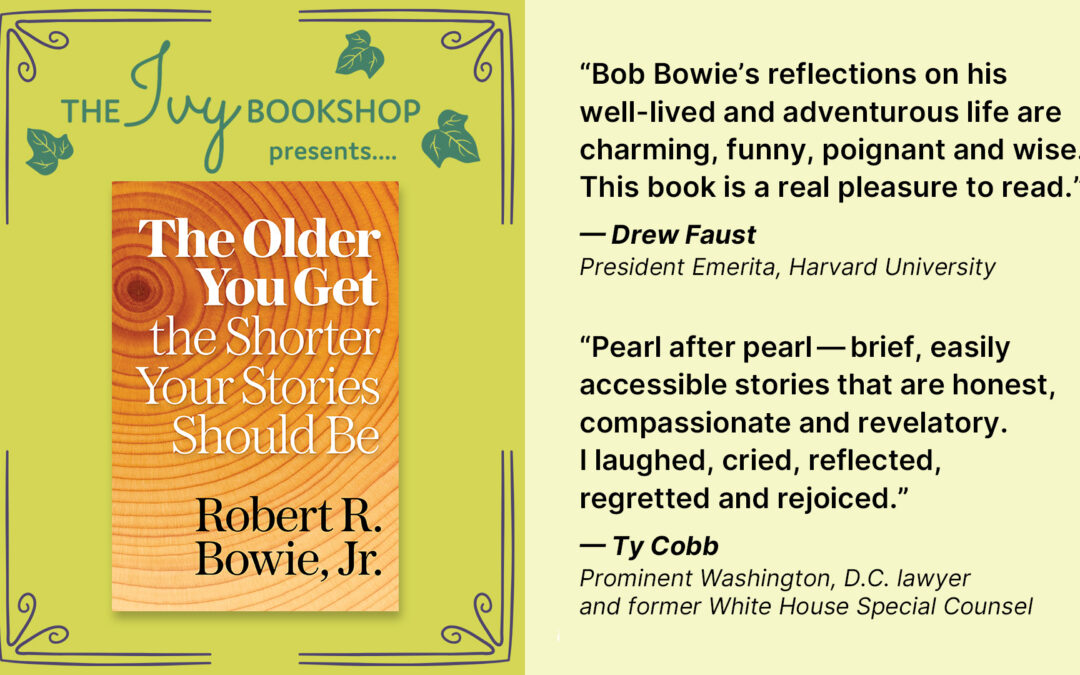

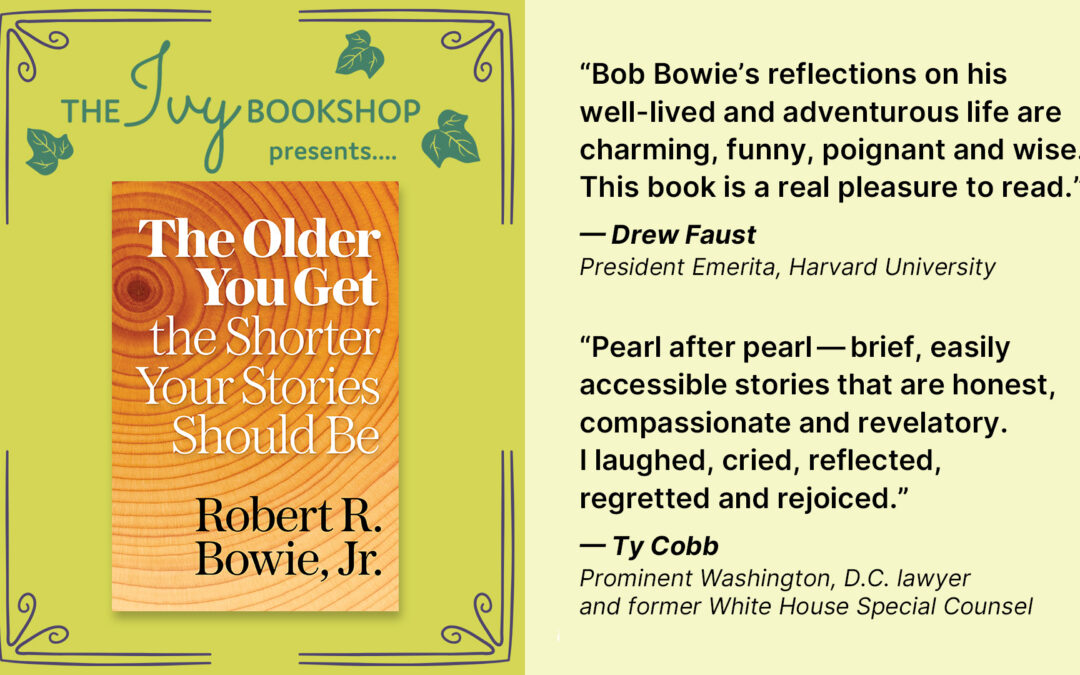

That story, which you just read, about my “streaking” through China is the very first story in my book, The Older You Get the Shorter Your Stories Should Be, which is now available at The Ivy Bookshop, The Manor Mill, Porter Square Books, or you can order from Bookshop.org (https://bookshop.org/shop/robertrbowiejr) or Amazon.com, where there’s even a Kindle version now! Or you can ask your any book store worldwide to order it using the following ISBN: 978-1628064209.

In addition, this book is perfect for regifting. Buy a copy for yourself. Tell your second recipient that you’ve road tested it because you care so much for them.

Finally, all the stories are short and perfect for your friends and family with short attention spans and they are great for deliberate bathroom reading and, of course, if you buy lots of copies you will make me really happy, too.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 30, 2024 | Featured, Personal, Travel

As we have walked around Paris you can feel the pride everywhere as the city prepares to host the Olympics. That pride is always there but perhaps now it is heightened, most evident in the city where you see the care and detail in the retail efforts. Whether they are the cafés, cheese mongers, or street markets full of fresh fruits and vegetables and fresh cut flowers, there is artistry in the display and even a little bit of competition between the storefronts. They are always careful and creative but some are so odd and distinctive you stop and join the fun.

I stopped by this statue with an indented empty bronze face (even though the photo makes it appear to protrude). Other statues behind the windows sit or stand and have the same hollow faces, empty but with no bronze. To the left is a paint can supported on a base made to stay in place by what it has already poured. Gold medal!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Mar 26, 2024 | Featured, Personal, Travel

Several weeks ago, my son and I went to Orioles spring training in Sarasota. I was careful to take lots of pictures, but after our last game it was odd how my thoughts unexpectedly returned to a trip I had taken earlier this spring. I was on a tour that followed where civil rights activists had marched 60 years ago from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in March of 1965, where they were mercilessly beaten as they tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

This abrupt transition probably did not take place for the reasons that you may imagine.

The Orioles played well and won most of the games that we attended. No, it was something other than that.

It was about living rather than photographing life, and what gets lost and what gets saved.

The Ed Smith Stadium, where the Orioles are encamped for spring training, holds less than 7,500 people. It is like watching Little League compared to Oriole Park in Camden Yards in Baltimore, which seats about 46,000.

The ushers that take you to your seats are all Baltimore retirees, snowbirds bright with their orange uniforms and big smiles. It is magical. The team prepares for the future in a library of memories in the Florida sun.

Our first game, we sat behind home plate and watched the field being lined as the seats filled up around us. It reminded me of when my children were young and we would go to minor league games in Frederick, or even to see the Bowie Bay Sox.

I’ve got the pictures to prove it.

Sitting behind home plate in the afternoon sun, we were up so close we could see how a 90-mile-an-hour fastball looked and sounded when it snapped into place in the catcher’s mitt.

The second game we were behind the Orioles’ dugout. You could see the faces of the players and read their expressions in a way that big league baseball cannot reveal on TV. The cell phones were all focused and the cameras were taking pictures.

Every other day, when the Orioles were traveling, we went to the beach. It was worthless to try to photograph and capture the enormity of going to the beach. The sand was bedroom slipper soft, and the sky was bright blue and huge. Shore birds flocked and fought for food scraps as people packed up, left the beach and went home. You just had to experience it with the sound of the waves and the bickering of the birds.

A photograph could not have captured the environment for memory. Without context, it was all too big and undefined to be described.

The night before we went home, we chose seats by the left field fence at the foul line.

We sat next to a young boy who desperately wanted to catch a baseball in his glove, which he kept squeezing and squeezing to our left. My son, who is a college football coach and had been a fourth-grade teacher, knows and loves kids this age.

As the players warmed up in left field between innings, we all got into the act as the players warmed up. We all were trying to get a player to give the young boy a baseball.

My son was quiet for a while until he encouraged the boy to get the ball himself. The boy’s older brother and father grew suspicious. My son encouraged the boy to leave the rest of us behind and go past the left field foul line to where the bullpen was located. There, he could watch the catcher and pitching coach as they were warming up the relievers between innings.

The boy went off on his own but we all could see the interaction between that determined young boy and that aging catcher and pitching coach because it was palpable, but still professional.

On his own, the boy built up his courage and made distant contact with the catcher and ultimately, at the end of the game, the catcher handed the pitching coach a ball, pointed at the boy, and the pitching coach went over and delivered the ball to him. All this was watched with bemused approval and excitement by the local crowd who had followed the little drama.

As we were walking back to the car after the game was over, I chastised myself for not taking pictures as the little story evolved. I remember the amazing joy on that boy’s face as he pounded and re-pounded the ball in his glove as he said goodbye and we went our different ways.

I remember from my tour reading the history of the march from Selma as I started across the bridge and over the brown river with its high banks, which I photographed excessively until I stopped midway across the bridge.

All the photographs I had taken were of a bridge before spring, where there was little life along the shoreline up and down the river. All of a sudden, I stopped photographing, and just looked and felt the river flowing beneath me. I imagined what the crowd must’ve felt with the locals and their law enforcement ready to beat the daylights out of the marchers if they moved a step further and they did.

I go over those photographs now, and I don’t catch the event the way I remembered it by looking at it and avoiding the photograph. I feel the same way about seeing that boy pounding that ball in his glove and smiling as we parted. Without context, it was all too big and undefined to be described. The memory may fade, but because I didn’t take the photograph, I saw it and the experience is still alive in me.