by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 28, 2020 | HAA, Man Machine, Personal, Poetry

Quarantine Journal Entry #*@!%😱!

On Friday, March 6th, I headed home on a mid-morning train from NYC. We had been busy. The day before, we had finished a third table reading of The Grace of God & The Man Machine. The atmosphere had been wonderful and the actors had greeted each other with hugs and kisses, celebrating the act of making theater.

Other than my wife, this was the last time I have been within six feet of anybody for almost two months. Everyone in the world I know is in quarantine.

I have tracked my friends in New York and elsewhere, as some of them have gotten the virus, gone dark, and returned to report they are better but have lost friends to the disease.

The realization that this will not end easily for anybody has been made clear every morning as I’ve watched a cold spring come to Maryland under iron gray skies. I have been waiting for good news or some sign of change. I want the everyday life that I will always remember but will not see again.

Today, I decided to gather the little things that I might have taken for granted before, and make them into an exciting life that must be coming.

My social media manager Katie Marinello has already posted the Hastings Race and Poverty Law Journal article written by Michael Millemann about the law school class that we taught with Eliot Rauh. We have been notified that it continues to be one of the most downloaded current articles. I read it, and instead of taking it for granted I celebrated it as part of a new beginning, a new opportunity.

A year ago this week, I recited my 7th annual Harvard Alumni Association poet laureate poem (a “serious” bit of frivolity which I dearly love). This year, because the alumni meetings will be held virtually, I was asked to write it and have it videoed for presentation tomorrow. Instead of being disappointed I will not see my friends and fellow alumni and present it to a live audience, I reviewed the video and found myself laughing.

Finally, the play I was afraid would die in New York City after that great reading, we have just been informed is a finalist for the New York Rave Theater Festival and is being considered for perforce in NYC in October.

A different world is evolving now, but at least personally it is starting to feel like we are starting to wake up from a sleepless night to a coming spring.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 14, 2020 | Featured, Personal

Being quarantined is like driving with your family at night when the government turns off your headlights.

First, you realize you must pull over because you don’t want to be stopped by an invisible tree or police officer.

The rest is endless waiting and the push and shove of group activity in a very contained space.

The driver instantly loses authority and the backseat gets more and more unruly. (This is an absolute truth.)

Actually, the seat belt is unbuckled for everybody.

There can be no consensus about the radio so it gets turned off.

Out come the cell phones, as people start thinking for themselves rather than for others, but there is no privacy so out come the headphones and the binge watching begins in strange existential silence.

Am I really watching “The Tiger King”?

The world outside the car is the enemy anyway, because no one can dress up to confront it. And worse, if they do, they must wear face masks and plastic gloves, which ruins the grooming and manicure.

As hope for alternatives disappear (“alternatives” are recognized to no longer be available), as a last resort we are confronted by our family and friends and the question:

“How did they happen?”

and

“Why did we end up in this car?”

It is not by accident.

Back when I was growing up in New England, the entire Northeast had a black out and nine months later the birth rate spiked!

You chose it. I don’t mean birth order—I mean you chose to get in the car. Is this car the architecture in which we chose to spend our precious time? Maybe? What are traffic jams anyway?

So why do cars have backseats? For procreation and the storage of loose children?

And this is who we end up with when the lights go out?

Oddly, as if by miracle, these strangers must be eventually confronted and recognized.

At different times for each of the people in the car, during their own moment of silence, something is recognized.

It is that you belong to them and they belong to you.

It happened to me. I am fortunate, and a little surprised to realize the “unexpected” has broken my status quo and given me an opportunity to get out of the car as a different person than when I got in it.

I am fortunate to have the friends and the wonderful extended family which I have.

But I had my moment.

I learned I don’t just want to travel with them. I want to appreciate them and not take them ever for granted and forget for a moment how much I love them again and again and again…

And why The Tiger King should probably end up in solitary.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Dec 3, 2019 | Featured, Personal, Politics

You can call it “fake news” or the subjugation of truth, but when confronted by self-serving diatribes and obstructionist partisan arguments, I saw several witnesses at the impeachment hearings persist and tell the truth — or at least preserve its credibility — no matter how difficult that was for them.

When I was a driver for U.S. Senator Charles “Mac” Mathias’s (R-MD) during the Watergate proceedings, news and politics were different than today. Credibility was everything.

On TV, Walter Cronkite delivered the truth on the CBS Evening News. He was voted the most trusted man in America.

The newspapers never had that power of personality, but they doggedly stood behind their stories, even when they relied upon undisclosed sources like “Deep Throat.” They knew they were at risk every day.

Credibility sold the news, and advertising, and paid for heavy overhead and lots of investigative reporters.

Today, news sources on the web do not need credibility. They have followers instead.

They are also not at risk because they have few, if any expenses, and are often not even identifiable. Social media is flooded with unverifiable news sources, some of which are paid for by our enemies as they seek to disrupt our country’s elections.

Senator Mathias was from Frederick, Maryland — farm country — two hours west of DC. He was fiercely loyal to his city and his state. He cherished his reputation for integrity and his nickname, “The Conscience of the Senate.”

It was different back then, but it is still the same.

I was driving Mathias when he was summoned by President Nixon to an afternoon rally the next day. Mathias was to be filmed beside Nixon for the evening news that night. Mathias had, in essence, been summoned to give the President an unspoken endorsement in Maryland’s Washington suburbs, in Mathias’s home state.

Maryland is an overwhelmingly Democratic state. Mathias was no fan of Nixon and Nixon knew it, but Nixon was a Republican and so was Mathias.

Credibility was everything to Mathias but he couldn’t say “no” to the president without punishment from his party.

I picked the Senator up at his home that morning and we headed to his scheduled meetings.

The first thing he said to me as he got into the car was, “looks like that tread on the left rear tire is thin.”

After the morning meetings and before lunch, I offered to take the car to get the tire checked, but Mathias said he wanted me inside to record his speech on the handheld tape recorder I always carried with me for such occasions. He made sure he was never misquoted.

After lunch, as he got into the car he pointed and asked me, “You think it looks like that tread is dangerous?”

I insisted that I get the tire checked immediately so we would be on time for the rally.

The Senator thought for a judicious moment. “I think you are right, Bob. Let’s get it looked at.” But as I turned into a filling station he quietly said, “I have always bought my tires up at the Goodyear store in Frederick.”

By the time we got back to Washington, the rally was over. As I let him out of the car that night, he asked me to remind him to send his apologies to the White House.

To maintain credibility in the face of power, persistence may not always offer the opportunity to speak the truth. But at least it’s a statement on its own: the resistance is a placeholder for the truth, and it retains our gravity.

It is different now, but it remains the same.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 29, 2019 | Featured, Personal

Last Friday, I skipped lunch and went back to my Boston hotel room to watch Congressman Elijah Cummings’s funeral on TV.

Thirty-five years ago, when he was still a lawyer, we had a case together. I was representing a modular building company and he was representing one of the prominent African American churches in Baltimore, which had contracted with my client to buy and construct a building for Baltimore city primary school students.

Elijah and I met on the top floor of the church overlooking North Avenue where the ministers’ offices were located. He came over, shook my hand, and said, “I do a lot of criminal law and you know a lot more about business law than I do. Can we agree to work to make this fair for both sides?” I shook his hand and agreed that would be our objective.

The contract negotiations and construction took some time. As the building went up, there were adjustments to the plans and “change orders,” as there always are in construction cases, but we were candid with each other and each time we got it right.

Years later, I was at the Democratic convention in Boston and he saw me and came over and with a big smile he said: “Yeah! We learned to work well together didn’t we?” We both laughed.

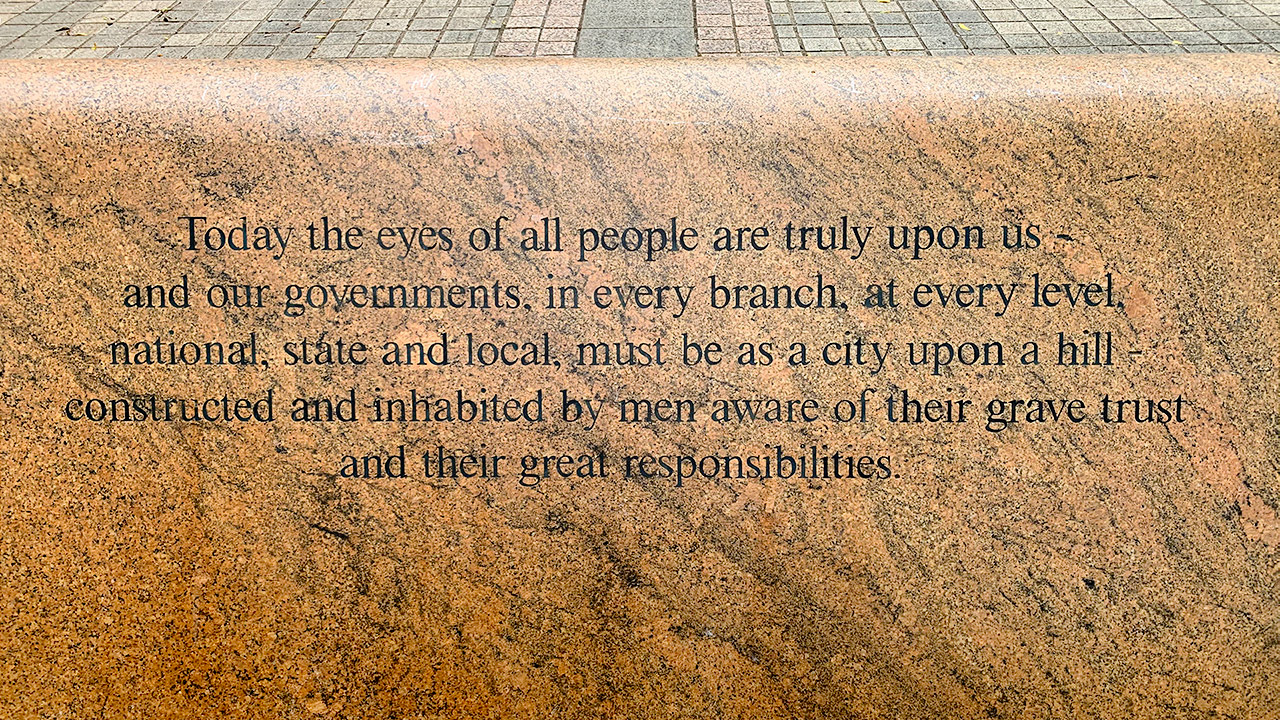

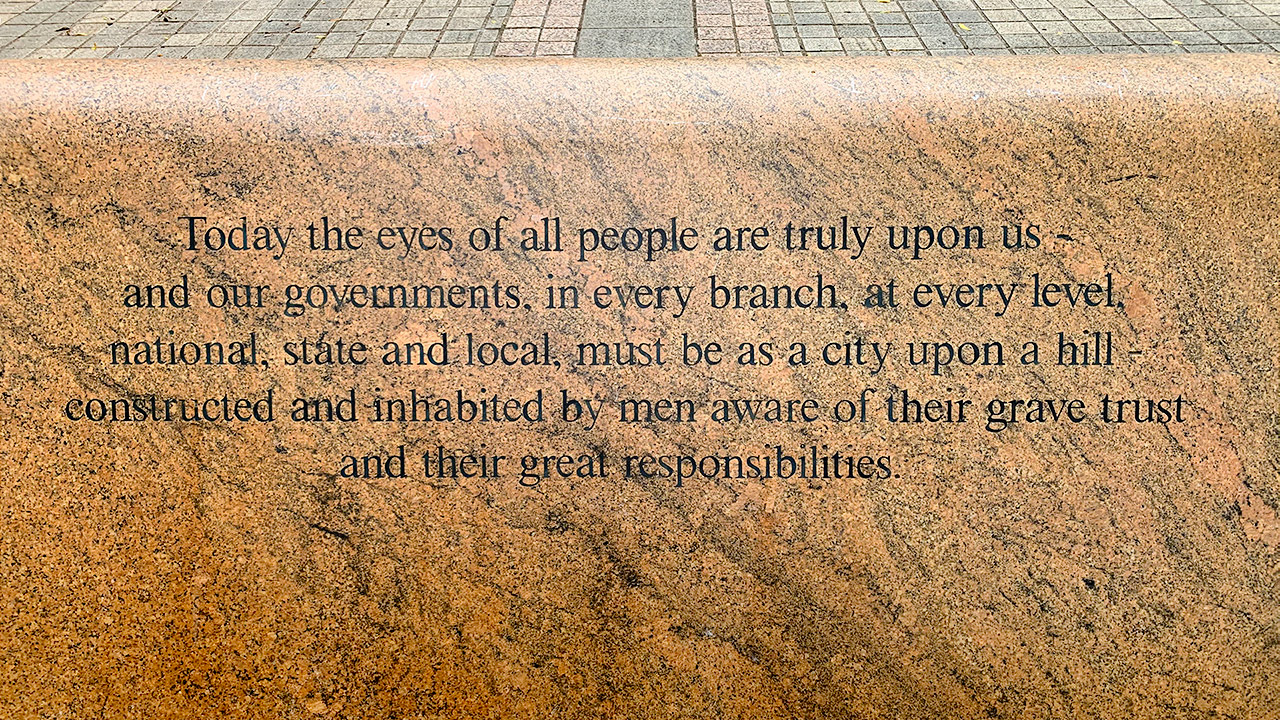

I grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and one of my favorite places is an old rusted fountain dedicated to John F. Kennedy. It no longer works but still has his quotes chiseled on its sides.

My hotel was in Harvard Square, so after the funeral I walk down to the fountain and read the quotes again:

“Today the eyes of all people are truly upon us — and our governments, in every branch, at every level, national, state, and local, must be as a city upon a hill — constructed and inhabited by men aware of their grave trust and their great responsibilities.”

Next to the forgotten monument was a sign that said: “No Skateboarding.”

No one was there except a skateboarder, practicing and re-practicing his art, and me.

It occurred to me that there are always laws which will be broken but we all, somehow, are subject to a deeper code. This was what Elijah understood.

Thousands of people, whether in the church or on TV, watched Elijah’s funeral. They watched and listened and were there because Elijah was an example of something we seem to not be able to forget.

Although in our daily lives and in our politics and governance it is sometimes lost, it is there in that handshake, that eye contact, that second thought that reminds us that it is as constant as gravity.

I saw Elijah on and off after that, in airports or at campaign events. He had become my Congressman. We would smile or wave. We were not friends, but we had once come to an understanding because he had offered up his vulnerability so that I could offer mine. And we could trust each other just long enough to do something right.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jul 9, 2019 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Poetry

As a lawyer I was your advocate, but now as a Poet my job is to help you see all things differently. For example:

I have a silver gray antique BMW Z3 convertible. It looks like a ridiculous self important go-cart. It has five gears and a stick shift. It is loud. It is very low to the ground and only my head sticks out of the top.

When I drive this car I am publicly on display as a self-confessed idiot. Sort of a clown. Young boys with fresh learner’s permits pull up to me at stop lights, rev their engines, and laugh at me. I should be embarrassed.

But if I tell you, “I know I look like an old man driving a roller skate…” you laugh — but once you’ve imagined me in this car, you look at the car and the old man differently. It may be funny or it may be sad, but as a poet I have that ability to make you see things differently .

It is the ability to break the mold that we all live in and take for granted, again and again and again. The cement truck pours and we instantly take for granted that hardening cement and live with those forms forever. Poetry has the ability to break what is permanent and make it new by presenting it differently.

When I write a poem or a play I am asking you to hear my voice, look through my eyes, and see the “flash” vision that I create out of what we live in and take for granted together. I am driving the same roads, obeying the same traffic lights, and stalled in the same rush-hour traffic as you are. I’m using the same language and your words but I am aware of the sound of the words and the rhythm of our shared language in order to create that “flash” of the vision I want to create: “The old man driving a roller skate.”

That is the poet’s work. I must jackhammer out of existence something you have seen in your imagination, perhaps forever.

Let me give you two “flash” examples. Two quick comic examples from the best Poet of the English language: Shakespeare describes a drunkard who is upchucking on the street as, “Speaking with a full flowing stomach,“ or snidely describes a couple in an illicit affair as, ”being a beast with two backs.” In a “flash,” he can help you imagine what you expect, differently.

The job of the Poet is to bring you back to before the cement truck came into your life.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 25, 2019 | Featured, HAA, Personal

For me, the “future” is like a churning cement truck going to a job. The “present” is the dump of the watery mixture and its slow and permanent hardening. The “past” are the hardened roads I travel on again and again and again. Only the gift of “accident” can break apart all three and only with “creativity” do I become released and reborn to grow into a maturing perspective.

Over the last six years, I have been chosen to help The Alumni Association at Harvard put on graduation. I look forward to this and accept with pleasure each year when it is offered. I dress up in a silly top hat and tails to escort the honorary degree recipients and their families at Harvard’s graduation. It is an unusual and informative experience.

Rick, my son, and I are very close. After graduating from Dickinson College, his high school asked him to return to Baltimore to teach and help coach their football program. During these years Rick continued his commitment to education by getting a Master’s Degree from the night school at Johns Hopkins University, which allowed him only one night a week free. During these years Rick and I had dinner together every Monday night.

Rick has always been a very kind and socially conscious person. Rick also has an encyclopedic understanding of football and its rules and strategy. Because there is a deep divide in the opportunities provided in our city, after several years of teaching and coaching at his private high school, Rick elected to join his former head coach and teach at Saint Frances Academy in downtown Baltimore.

The year before Rick joined this school, it had only won one game. The next year, they were undefeated. The following year, they were ranked fourth in the nation.

All of the students on the football team went on to established and respected universities with mostly full scholarships. Rick told me several times that they were the most committed group of young men he had ever met. The school is located in the shadow of the penitentiary.

Rick continued his commitment to both education and football by accepting a graduate assistant position at the University of West Virginia, then followed his coach to the University of Houston. The last two years he has been working 24/7 as a GA for University of Houston’s football team and I never see him anymore.

So those are my hardened roads leading up to this year’s Harvard graduation. Here comes the cement truck: The week before my graduation duties this year, Rick called and said he had a free week. I wanted to see him desperately but I had made my commitment months ago. I asked him, “Do you want to come to Boston?” I couldn’t think of anything more boring for him but he said, “Sure.”

Was this a disaster about to happen or was this a gift of an accident? Rick would not know anybody…

We did everything together. A wonderful lunch with Rick and Lindsey Shepro and John Bowman at B&G oysters (Boston’s best oysters), and a dinner after graduation with Sam and Wendy Plimpton at No.9 Park (Boston’s best restaurant).

It is not easy to be shocked as you watch your child become, before your eyes, more sophisticated than you are. My old friends became his new friends almost instantly. And then we slipped back to our welcome past and beer and a Bruins game on TV and a Red Sox game at Fenway… and a stunning and subtle speech by Angela Merkel in the afternoon of graduation.

So often now, as I become older and easily set in my ways, I look for the gift of the “accident.” It breaks my safe world apart. From broken expectations comes the unexpected rebirth.