by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 29, 2019 | Featured, Personal

Last Friday, I skipped lunch and went back to my Boston hotel room to watch Congressman Elijah Cummings’s funeral on TV.

Thirty-five years ago, when he was still a lawyer, we had a case together. I was representing a modular building company and he was representing one of the prominent African American churches in Baltimore, which had contracted with my client to buy and construct a building for Baltimore city primary school students.

Elijah and I met on the top floor of the church overlooking North Avenue where the ministers’ offices were located. He came over, shook my hand, and said, “I do a lot of criminal law and you know a lot more about business law than I do. Can we agree to work to make this fair for both sides?” I shook his hand and agreed that would be our objective.

The contract negotiations and construction took some time. As the building went up, there were adjustments to the plans and “change orders,” as there always are in construction cases, but we were candid with each other and each time we got it right.

Years later, I was at the Democratic convention in Boston and he saw me and came over and with a big smile he said: “Yeah! We learned to work well together didn’t we?” We both laughed.

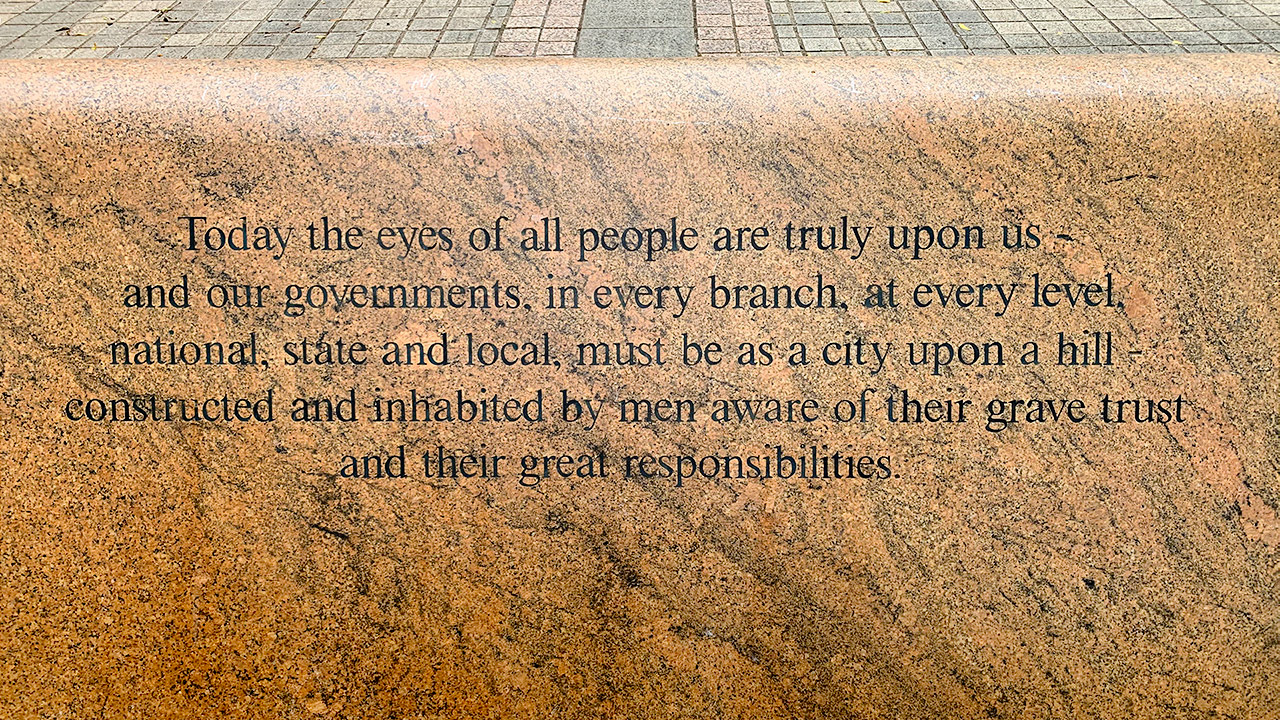

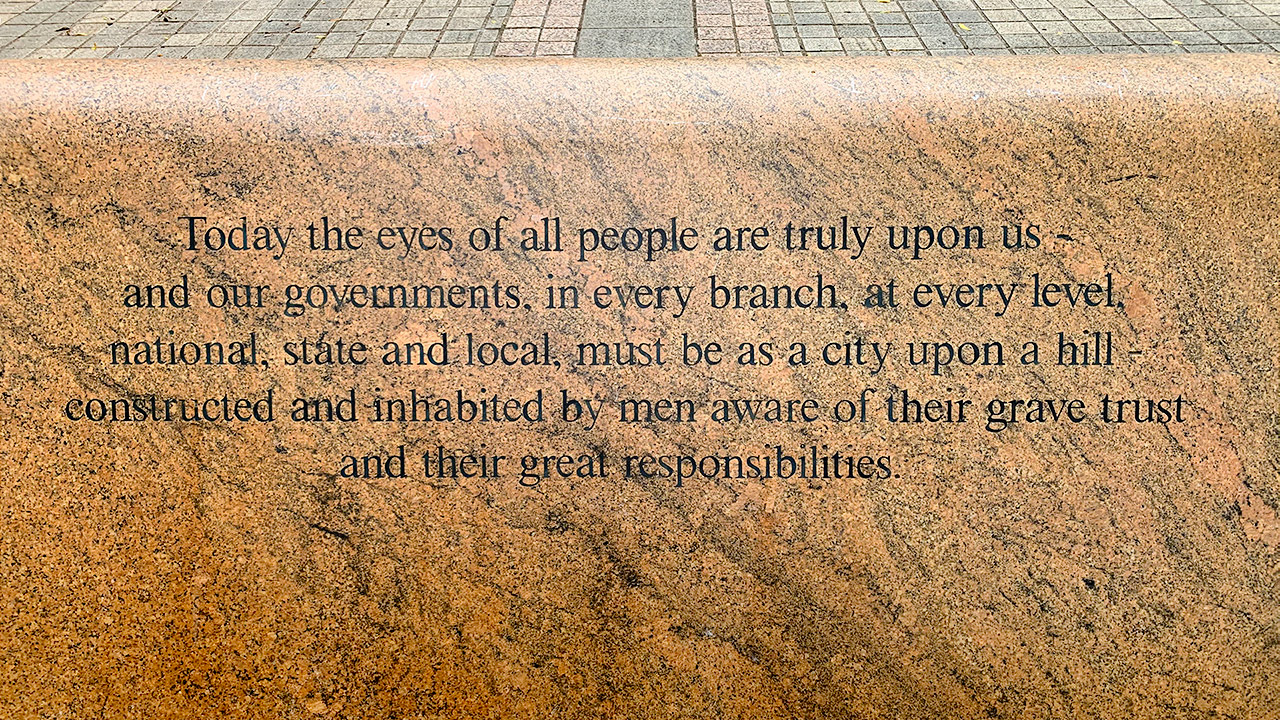

I grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and one of my favorite places is an old rusted fountain dedicated to John F. Kennedy. It no longer works but still has his quotes chiseled on its sides.

My hotel was in Harvard Square, so after the funeral I walk down to the fountain and read the quotes again:

“Today the eyes of all people are truly upon us — and our governments, in every branch, at every level, national, state, and local, must be as a city upon a hill — constructed and inhabited by men aware of their grave trust and their great responsibilities.”

Next to the forgotten monument was a sign that said: “No Skateboarding.”

No one was there except a skateboarder, practicing and re-practicing his art, and me.

It occurred to me that there are always laws which will be broken but we all, somehow, are subject to a deeper code. This was what Elijah understood.

Thousands of people, whether in the church or on TV, watched Elijah’s funeral. They watched and listened and were there because Elijah was an example of something we seem to not be able to forget.

Although in our daily lives and in our politics and governance it is sometimes lost, it is there in that handshake, that eye contact, that second thought that reminds us that it is as constant as gravity.

I saw Elijah on and off after that, in airports or at campaign events. He had become my Congressman. We would smile or wave. We were not friends, but we had once come to an understanding because he had offered up his vulnerability so that I could offer mine. And we could trust each other just long enough to do something right.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 22, 2019 | Featured, Poetry

Working on the libretto for the operetta, Vox Populi, has brought me back to my love of poetry.

My favorite poems create a universe with a few words. Two good poems with a similar subject, put side by side, can introduce the creator of the other.

Like a painter organizes color and shape with his or her brushstrokes, the poet organizes a vision with the sound and rhythm of words:

“Whose woods these are I think I know./

His house is in the village though;/“

The brushstrokes? The sound and rhythm of these two lines? Speak them out loud. They are like the rocking of a hammock they are so smooth and quiet.

In complete contrast however:

“I sought a theme and sought for it in vain,/

I sought it daily for six weeks or so./“

Brush strokes? This is not like the rocking of a hammock, it is like riding a three-legged horse.

Those are the opening two lines of two completely different poems by two completely different people. Now let’s look at the last two lines of these two poems.

“And miles to go before I sleep./

And miles to go before I sleep./“

Brush strokes? The same rocking hammock. Compared to:

“I must lie down where all the ladders start,/

In the foul rag-and- bone shop of the heart./“

That must’ve been a hell of a rough ride? You are correct.

They are both about the end of life. The first by Robert Frost is entitled “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” and the second by WB Yeats is in titled “The Circus Animals’ Desertion.”

Both are about “acceptance,” it seems to me, but that acceptance comes in completely different, very personal forms. Frost’s, in a late evening snowy New Hampshire woods, and Yates’, with the casting off his “Circus Animals” (his life’s work of Irish themes).

The libretto for the operetta is meant to be baudy and entertaining. My poetry, on the other hand, is a personal statement that is directed from me to the reader. It’s from my heart.

I have placed links to both poems below for your review and your own contrasts and conclusions. Feel compassion for these two people. They are writing because they are reaching out to you.

“Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost

“The Circus Animals’ Desertion” by W.B. Yeats

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Sep 24, 2019 | Featured, ONAJE, ONAJE Update, Operetta, Plays, Travel

So his fool tells King Lear: ”Thou shouldst not have been old till thou hadst been wise.”

I am 72 years old today and one step further into my next life. No not the afterlife… the next step and the opportunity of freedom which that entails. As it’s my birthday, I hope you’ll allow me this time to reflect…

I decided to start this blog several years ago to chronicle what would happen to me in retirement. I loved the practice of law, but concluded that there is a time to retire before you get in people’s way and can’t find the bathroom. I wanted to stay a little bit ahead of that curve so I got out early.

I already knew that eccentricity and determination always trumps a loss of intelligence. So this was my chance to be free to try something entirely different, but I still was not free of trepidation. Delusions of grandeur are a wonderful thing until you start to think you might act on them.

Nonetheless, I first decided I would become a “political force” as a Democrat in an entirely gerrymandered Republican district because I was very concerned about how we, as a country, were being divided by political forces and I was going to change that. This was Trump country. I raised more money than all my Republican opponents combined and knocked on almost 7000 doors for more than a half a year. I was resoundingly defeated and Trump became our president.

Because I obviously had learned nothing about impossibility, next I decided I would become a professional playwright. I bought a Shakespeare coffee mug and applied to the Yale Drama school, fully believing that I would be the oldest applicant ever accepted to Yale’s drama school. I succeeded only in becoming the oldest applicant ever rejected by Yale’s drama school. Nonetheless, I had decided this is what I wanted to do.

Obviously I had to rethink this thing again, with just a little more of my failing intelligence. So I applied to the Commercial Theater Institute (CTI) of New York for a class in producing theater. I had a plan. When the first morning of class broke up the students got lunch and inevitability they talked about what plays they were considering producing. When it came to my turn to talk I informed them I wasn’t considering producing anything. I wanted them to produce me. It worked. The impossible happened. A young producer agreed to read my work, liked it and arranged for professional staged readings in San Francisco and later in New York.

Because I had excelled in something I didn’t want to do and I had completed an introductory class in it, I applied for an advanced class in producing at the prestigious O’Neill Conference in Waterford Connecticut. I got in and there I met Sue Conover Marinello, who produced my play Onaje with great success last year in New York, and Christian De Gré Cardenas of Mind the Art Entertainment who has an amazing history of producing and also writing the music for a number of amazing operettas in New York. Both became friends.

After Sue Conover Marinello’s production of Onaje in New York, Mind the Art commissioned me to write the libretto for an operetta, Vox Populi, a comedy about the seventh deadly sin of pride, for Christian’s music. Last month, Christian and I completed the operetta in San Miguel Mexico.

Because Onaje had done so well, Sue convinced Kevin R. Free, the wonderful NYC director, to read the script. Kevin had fresh and original insights which lead to my reworking the script and his commitment to direct its next production.

The blog has become a happy travelogue. It is a history of mistakes and opportunities. It has taught me that even though I may not succeed in any of this, I’ve lost the fear of failure and each day is more fun than the last. The next step into a new thing is the hardest thing I ever do but it is getting easier with age.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 8, 2019 | Featured, Poetry, Travel

As I turned away from Degas’ statuette of a dancer at the Musee D’Orsay in Paris last week, I almost missed the imitators. The imitators were lining up, looking at the statuette and striking a pose. The reaction was not mocking and somehow not disrespectful. The imitators were reacting to a man-made object created out of his imagination. The interaction is what mattered.

When I was in high school, I read a line from W. H. Auden that said “poetry makes nothing happen.” It stopped me in my tracks. It was the late ’60s. I wanted to do things that made things happen. I became a lawyer. I made things happen.

Now I know I misread the line. Auden was making fun of all those things that appear to make things happen but really don’t. Art makes things happen in that it offers the chance to interact with a created object from another person’s imagination.

But why does that matter? It seems that at the center of our existence we travel a number of years in the mundane pursuit of what we need to survive, but art offers a conversation with another who is, or has been, on that same journey. It offers, but does not demand, this conversation.

In the same gallery, hordes of people were moving from picture to picture, cell phones out, photographing the exhibit as they hurried by. They had not accepted the offer. They were just capturing the object.

The imitators had accepted the offer. They were interacting with the Degas’ statuette.

The conversation can happen in many forums but it is always between the artist and the self. It can come through some or all the senses. It can be theoretical. It can come with an artist’s demand for your attention, as with Andy Warhol asking you to notice common objects, but for me it is always a very personal person-to-person communication.

It can also be environmental. On my way home, I noticed the statues in the park and the park in the city as I walk through. The art of the statue inside the art of the park surrounded by the mundane existence of the traffic and commerce of the city.

I found Auden’s quote:

“For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.”

In Memory of W.B.Yeats

(d. Jan. 1939)

He says all this better than I but I had to learn it for myself.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 1, 2019 | Featured, Travel

It is almost impossible to describe the First World War in simple terms. It is unresolved as to how it evolved into the war it became — the number of casualties it caused easily exceeds eight million dead and double that in maimed and wounded — and its end probably was the beginning of the Second World War only twenty years later. Books and books and books continue to be written about it. It is a wellspring of scholarship and a mirror for the future and present.

There are two things it demonstrates to me, however. First, we seem to be incapable of maturing at the same speed as our ability to make weapons evermore capable of our mass destruction. Second, we seem to be able to commit ourselves blindly to use these weapons without realizing the extent of the destruction that we can cause. Both of these observations demonstrate the incredible capacity we have in the form of the “nation state” to destroy ourselves, despite our individual capacity to feel compassion, empathy, and kindness for each other on a daily basis as human beings who are not in a state of war.

Why have I attached a picture of a crater?

WWI introduced airplane warfare, submarine warfare, the machine gun, the tank, and gas warfare. The warfare was so intense that there are specific monuments dedicated to both missing soldiers and unidentifiable body parts.

So, is there something, a simple example from this war, that demonstrates redemption? Yes, I think there is.

Both sides built tunnels for days and months for incredible distances under entire towns and enemy lines to set explosives. Some of these tunnels were only four feet wide and three-and-a-half feet high. The excavation of the dirt was extremely difficult and endlessly time consuming. Imagine the commitment. Imagine the claustrophobia. Imagine the amount of explosives that then had to be carried underground to blow up a town or an enemy stronghold.

As I have said, the picture I have provided is of a crater. It is thirty to forty feet deep and almost a football field wide. The explosion sent debris four thousand feet in the air and killed and injured people who were never found. I took the photograph from the far side. There is a monument on the other side which, if you look closely, is a cross that is several stories high.

In the alternative, it has been documented that during a one-day armistice for Christmas the soldiers from both sides came out over their trenches, exchanged chocolate and cigarettes, and sang Christmas carols together.