Two weeks ago, I wrote about Professor William Alfred, my tutor in college, and how my affection has grown for him. Today, I will remember the other mentor for whom I have a continued and growing affection.

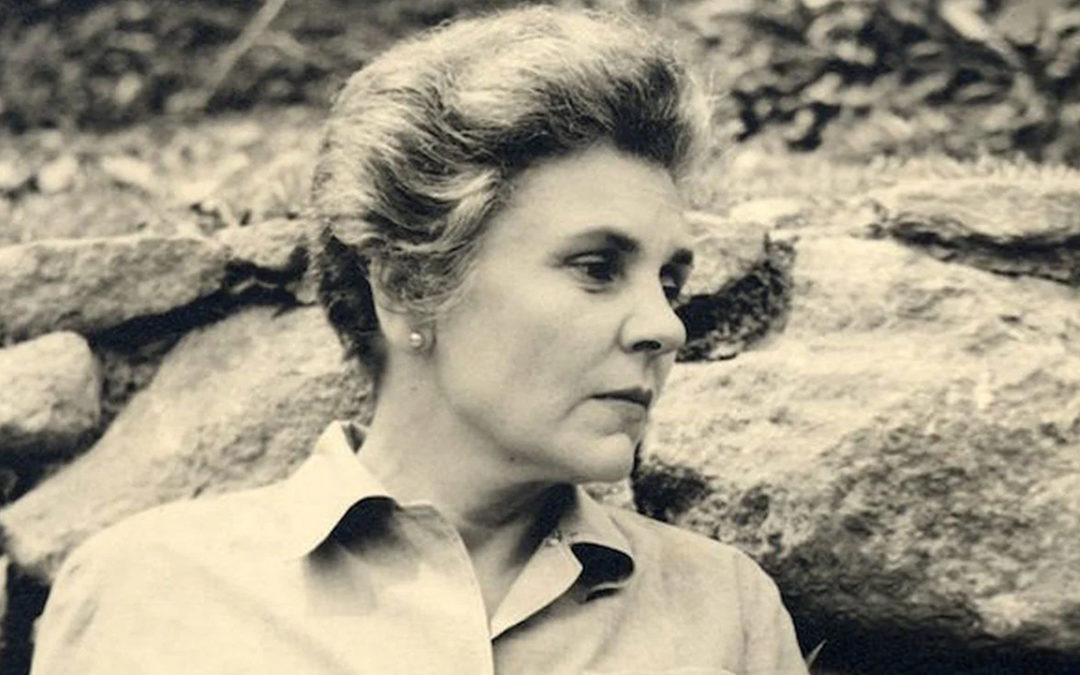

Elizabeth Bishop (1911–1979) was, and still is, a very respected poet of the late 20th Century. She lived a hard life filled with loss and loneliness. She was raised and passed around by her maternal grandparents and relatives after her father died when she was a year old and her mother was placed in a mental hospital.

After she got into and graduated from Vassar, because she had no traditional family to surround her, she found comfort in travel. In late midlife, after her partner with whom she lived in Brazil for years died, she was alone again. Robert Lowell convinced Harvard to offer her a chance to teach there.

In order to get into her class in the fall of 1972, I had to submit an essay on the Wallace Stevens poem “The Emperor of Ice Cream.”

It starts:

Call the roller of big cigars,

The muscular one, and bid him whip

In kitchen cups concupiscent curds.

It is a difficult poem. It is like a description of a carnival with its cigar rollers and ice cream makers but it is about the preparations for a Cuban funeral. It is a celebration of life, not a celebration of the dead person. The end of the first stanza reads:

Let be be finale of seem.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.

From my first reading it struck me personally as being so godless and lonely. It ends with this:

If her horny feet protrude, they come

To show how cold she is, and dumb.

Let the lamp affix its beam.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.

Years later, I found in her letters her description of how she had decided to choose that poem for the competition.

She was walking alone past Brigham’s Ice Cream in Harvard Square toward Kirkland House where she would make copies of the poem she had chosen for the competition and leave it with Alice Methfessel, a staff person at Kirkland House, to hand out to the competitors.

Alice would, a few years later, become the executor of Bishop’s estate.

It was a small class limited to around 10 to 12 people. She required that each student memorize 15 lines of two 20th Century poets for each class. She was insistent. When she pointed at us in class, we had to recite our chosen poems.

She told us it was a way to bring a poem alive again. When it was recited in a different environment it will be different than reading it from a book again and again. It was like a friendship you could carry with you.

Bishop did not appreciate self centered over egoed undergraduates. I was a little older myself. From the beginning, I believed I felt her loneliness and I imagined she felt mine, but I wrote it off as my imagination.

I worked very hard in Bishop’s class and she saw the depth of my interest and commitment. I didn’t speak up much but I was always prepared for class. I never made intentional eye contact but I found that midway through the term she smiled after I had participated, and by the end of the year we would even talk briefly as we were leaving class to reenter the Square.

We talked about things rather than poems when we chatted. This was a time when confessional poetry was on the rise and people wrote very personally about their families and themselves extensively, but Bishop by nature was reserved and private. She wrote about things that were indirect, but they were very moving and profoundly personal.

No one believes me now, but I misread the instructions for the first hour of the three hour blue book final exam. The instruction required that we were to write out verbatim half of all those poems that we had memorized. I wrote out all of them.

I got an A from her and Professor Alfred was pleased because she had a reputation for being a hard grader.

I asked her to write a recommendation when I applied to law school. She agreed but I was surprised to almost sense she thought my choice was a little misguided given my obvious love of the arts. I don’t think she thought too highly of lawyers.

Years later, well after she had died, I was surprised to learn her recommendations could still be found at Kirkland House, so I asked to see her’s of me and when I read it, and proudly made a copy, I discovered something.

She wrote a short but glowing recommendation but she concluded:

“… but I feel he has great abilities, and possibly talents, he is not aware of himself… Mr. Bowie has worked very hard and has a very original cast of mind. I recommend him highly.”

What an odd and gratuitous comment for a law school recommendation, I thought. Did she know someday I would find it?

And then I smiled as if she had touched my hand.

She had cared about me. And as I stood there rereading my Xerox copy, I felt affirmed and supported to continue on this, my late life journey. She had noticed me.

Photo: Archives and Special Collections, Vassar College Library