by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jan 10, 2023 | Featured, Personal, Poetry

Two weeks ago, I wrote about Professor William Alfred, my tutor in college, and how my affection has grown for him. Today, I will remember the other mentor for whom I have a continued and growing affection.

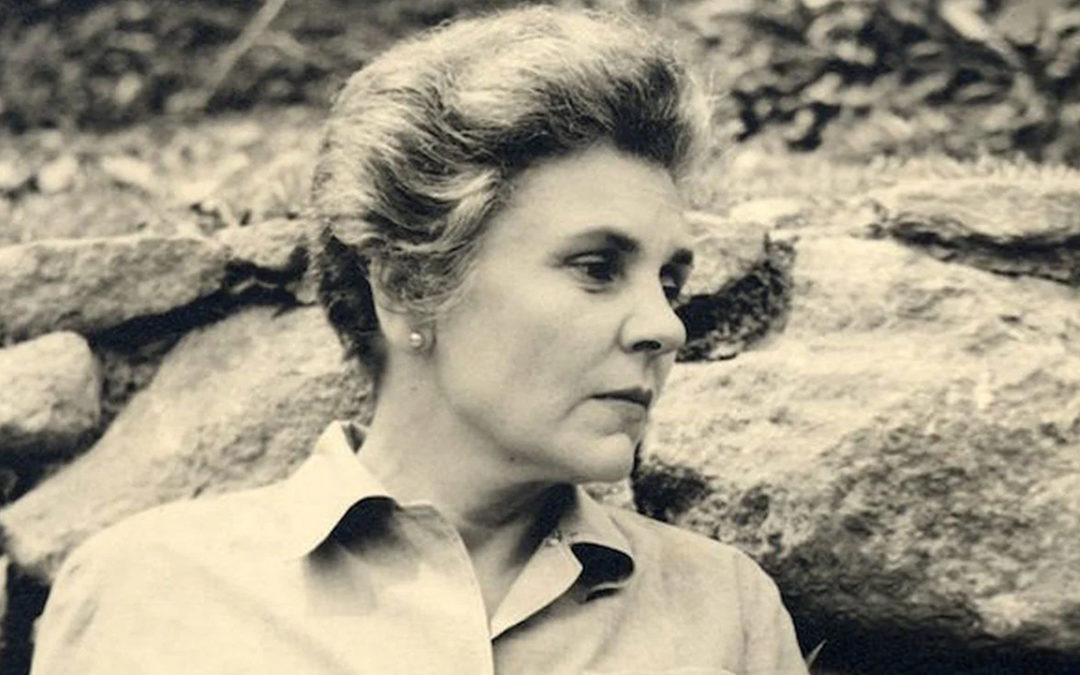

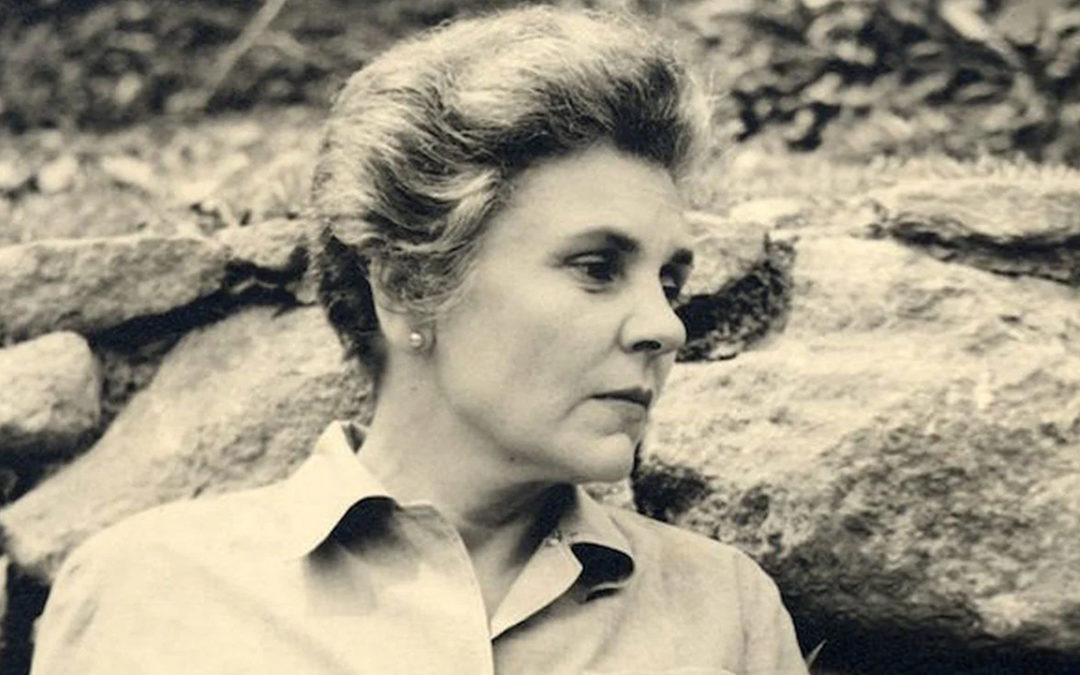

Elizabeth Bishop (1911–1979) was, and still is, a very respected poet of the late 20th Century. She lived a hard life filled with loss and loneliness. She was raised and passed around by her maternal grandparents and relatives after her father died when she was a year old and her mother was placed in a mental hospital.

After she got into and graduated from Vassar, because she had no traditional family to surround her, she found comfort in travel. In late midlife, after her partner with whom she lived in Brazil for years died, she was alone again. Robert Lowell convinced Harvard to offer her a chance to teach there.

In order to get into her class in the fall of 1972, I had to submit an essay on the Wallace Stevens poem “The Emperor of Ice Cream.”

It starts:

Call the roller of big cigars,

The muscular one, and bid him whip

In kitchen cups concupiscent curds.

It is a difficult poem. It is like a description of a carnival with its cigar rollers and ice cream makers but it is about the preparations for a Cuban funeral. It is a celebration of life, not a celebration of the dead person. The end of the first stanza reads:

Let be be finale of seem.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.

From my first reading it struck me personally as being so godless and lonely. It ends with this:

If her horny feet protrude, they come

To show how cold she is, and dumb.

Let the lamp affix its beam.

The only emperor is the emperor of ice-cream.

Years later, I found in her letters her description of how she had decided to choose that poem for the competition.

She was walking alone past Brigham’s Ice Cream in Harvard Square toward Kirkland House where she would make copies of the poem she had chosen for the competition and leave it with Alice Methfessel, a staff person at Kirkland House, to hand out to the competitors.

Alice would, a few years later, become the executor of Bishop’s estate.

It was a small class limited to around 10 to 12 people. She required that each student memorize 15 lines of two 20th Century poets for each class. She was insistent. When she pointed at us in class, we had to recite our chosen poems.

She told us it was a way to bring a poem alive again. When it was recited in a different environment it will be different than reading it from a book again and again. It was like a friendship you could carry with you.

Bishop did not appreciate self centered over egoed undergraduates. I was a little older myself. From the beginning, I believed I felt her loneliness and I imagined she felt mine, but I wrote it off as my imagination.

I worked very hard in Bishop’s class and she saw the depth of my interest and commitment. I didn’t speak up much but I was always prepared for class. I never made intentional eye contact but I found that midway through the term she smiled after I had participated, and by the end of the year we would even talk briefly as we were leaving class to reenter the Square.

We talked about things rather than poems when we chatted. This was a time when confessional poetry was on the rise and people wrote very personally about their families and themselves extensively, but Bishop by nature was reserved and private. She wrote about things that were indirect, but they were very moving and profoundly personal.

No one believes me now, but I misread the instructions for the first hour of the three hour blue book final exam. The instruction required that we were to write out verbatim half of all those poems that we had memorized. I wrote out all of them.

I got an A from her and Professor Alfred was pleased because she had a reputation for being a hard grader.

I asked her to write a recommendation when I applied to law school. She agreed but I was surprised to almost sense she thought my choice was a little misguided given my obvious love of the arts. I don’t think she thought too highly of lawyers.

Years later, well after she had died, I was surprised to learn her recommendations could still be found at Kirkland House, so I asked to see her’s of me and when I read it, and proudly made a copy, I discovered something.

She wrote a short but glowing recommendation but she concluded:

“… but I feel he has great abilities, and possibly talents, he is not aware of himself… Mr. Bowie has worked very hard and has a very original cast of mind. I recommend him highly.”

What an odd and gratuitous comment for a law school recommendation, I thought. Did she know someday I would find it?

And then I smiled as if she had touched my hand.

She had cared about me. And as I stood there rereading my Xerox copy, I felt affirmed and supported to continue on this, my late life journey. She had noticed me.

Photo: Archives and Special Collections, Vassar College Library

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Dec 20, 2022 | Featured, Personal, Poetry

I have been discovering that love grows over time with reflection.

In 1965, Hogans Goat, a verse drama about love and politics set in turn-of-the-century Irish Brooklyn ran for over 600 performances on Broadway. It was written by Harvard Professor William Alfred, about the world in which he had grown up. In the early ’70s it was made into a movie.

Alfred was a legend at Harvard. Everyone loved him because he was completely approachable, lived in unassuming rumpled clothes, and had a habit of giving all the change in his pocket to the street people in Harvard Square. He knew some of them by name.

As a teacher, he was beloved because he taught an unbelievably good class on Beowulf, old English, and poetry in Sanders Theater every year to well over 500 adoring undergraduates. That is a testament to his talent.

He lived alone in a little house on Athens Street just outside of Harvard Square.

I was terrified when I was admitted as a transfer student to Harvard. The summer before my first classes, I had seen Hogan’s Goat on TV. It was great. I couldn’t get enough of it.

I was terrified of the place but I was a determined starstruck groupie with a plan.

As soon as I got my student ID, I went to Nick at Brattle Florist in Harvard Square. Nick was a proprietor and a friend. I had started buying corsages from him in high school, and I loved just going into his shop to talk to him.

I had decided to buy flowers and knock on Professor Alfred’s door to tell him the truth about being a starstruck groupie who just wanted to meet him.

Nick told me that Professor Alfred came in regularly, so he knew his favorite fresh flowers.

I took my bouquet early in the afternoon to Professor Alfred’s little house. I carefully ascended the three steps and almost knocked on his door, but I lost my nerve. I made two more passes before I finally knocked on the door and waited.

When he answered, I immediately straight-armed my flowers at him as I stood on the top step and I told him I was a transfer student who knew no one but I was a big fan of his and then I turned to go. He thanked me and to my surprise he said, ”Come in. I’m making tea.”

I entered into his little living room and sat in one of the wing chairs next to a little fireplace with a small clock on the mantle.

Professor Alfred returned with the flowers in a vase and a pot of tea with cups. He settled in and started to ask me questions. I was caught completely off guard. I talked too much about myself because I was nervous. But finally, I had the sense to ask him questions about the play as I kept an eye on the little clock on the mantle. I did not want to outstay my welcome, but I didn’t want to leave.

After almost 25 minutes, I stood up and apologized for staying so long, and Professor Alford asked me, “Do you have a tutor?” I didn’t know what a tutor was so I was sure I could confidently tell him, “No, I don’t.” He promptly replied, “I can be your tutor.” I promptly accepted, even though I had no idea what that meant.

That night, I went to my first dinner at Kirkland House, my new dorm along the river. I had been assigned a room and I told the three or four boys who randomly settled their trays at my table that I was a transfer student and I wondered if they knew what a tutor was. I was told it was like a graduate student who was sort of an academic big brother. I told them I had randomly met Professor Alfred that afternoon and he had offered to be my tutor.

My dinner companions were shocked. “You’re kidding! Alfred is your tutor?” The next day, I rented a room on Putnam Avenue and never stopped studying for fear I would flunk out.

I was convinced that once my fellow classmates at Harvard discovered how stupid I was, it would be the rage of the campus and I would be pointed out continuously, so I never moved in to Kirkland house.

For two years, once a week at 8:30 a.m., I met Professor Alfred and we studied poetry together. At the end of each meeting he would ask, “What do you want to learn next week?” There were no limits. We talked about Greek metrics and rhymes in English and non-English in translation, and poetry all the way back through Beowulf.

In the spring, we would set up two chairs in his little backyard and he would feed the squirrels by hand as we talked. Quite unconsciously, he became my poetic surrogate father. In short, I fell in love with the man, the devout Catholic, the humanitarian and the poet.

He would at times quote from memory poems he liked. One time, he quoted: “There is in God (some say) a deep, but dazzling darkness…”

It was by Henry Vaughan (1621–1695), but I didn’t take in the rest of it. His recitation had stopped me in my tracks because of the way he delivered it. He measured out the rhythm in the air and there was an intensity in the way he looked at me that made me lose my concentration.

Although Professor Alfred was in late middle age, he loved life, and I loved that he rose to almost any occasion.

One morning as I entered, Robert Lowell, the famous poet was leaving. Professor Alfred explained, “Cal wanted to go see the artistes last night.” They had gone down to the “combat zone“ in Boston because Lowell, the old Brahman, very much out of character, wanted to see the strippers at work.

One morning as I entered, Faye Dunaway, the star of Hogan’s Goat, and Peter Wolf, the lead singer for The J Geils Band, were on the couch in the living room. The two had obviously been on a very creative overnighter, and Alfred had sat up with them because they were friends.

I graduated with honors in 1973, and when I would visit Boston or Cambridge I’d visit Nick to pick up flowers and knock on Alfred’s door. If he was in we would always talk.

It was always professor/student but it was always friend to friend. The phone would ring occasionally, and he would smile and say, “They will call back I am certain,” and we would talk some more. The friendship ripened and grew stronger over time.

In June of 1999, I traveled up to Cambridge and ambled into the Brattle Street Florist, found Nick and requested my customary bouquet of flowers. Nick looked up from the flowers he was arranging for a customer. He dried his hands as he stopped his work to talk to me. He faced me, paused, and said “He died last month. He’s up in the Harvard lot in Mt. Auburn Cemetery.”

I read last month in The Crimson that the Brattle Florist would be closing.

Nick had died but I stopped there when I was in Cambridge and got flowers. I took them to Mt Auburn and found Alfred’s grave below the tower, up the hill.

The gravestone read:

“There is in God (some say)

A deep, but dazzling darkness.

Oh, for that night where in him

I might live in visible and dim.”

I had missed those last two lines when he’d read them, which defined him perfectly.

There was no one around, so I spent a lot of time with him, and when I got up, my knees were wet from the ground. I think I loved him more then than I ever had before.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Dec 6, 2022 | Featured, Personal

You do know logic has its limits…

If you spend a lot of time outside the reach of sunlight, it can create two different parallel psychological worlds.

Back when I was in college, the world was roughly broken into those who believed that “you are what you eat” and those who believed “you are where you smoke and drink.”

It was sort of like the difference between light and dark.

It was the health food people of the Age of Aquarius vs. the hedonists. It was the difference between “Hello,” which has one meaning, and “Hi,” which has two.

Back in college, I was a bartender in a now defunct basement bar in Harvard Square that had no windows.

Upstairs was a high-end restaurant. Its clientele would briefly wait for their table while the rest of our patrons were occasional walk-ins from the street or the regulars who had self-imposed assigned seating every night around the horseshoe shaped bar at which I held court.

There was a juke box and maybe ten small tables with un-emptied ashtrays and an electric candle with a little red shade. I noticed the atmosphere was not conducive to romance when I would announce last call.

Because I am a caring person, I learned that I could control the future behavior of the patrons from behind the bar.

If I turned the jukebox up, dimmed the lights and mixed strong drinks, I could make a wild party, but if I wanted calm, I could make weak drinks, turn up the lights and turn down the music.

Also, because I was a caring person, I got to thinking there could be variations on this theme: Consider strong drinks, dim lights and soft music when I announce last call. Much better. More conducive to romance, or at least intimacy.

Now consider each table as an event onto itself. Dim lights, soft music, and half price to try a glass of our new champagne.

Hey! We making babies now!

I got to thinking I had magic powers, that I was sort of an invisible Cupid.

Wait! No! That’s what too much darkness will do to you.

At that very moment, I realized that I was no longer a caring person. I had become a puppeteer!

I didn’t want to think of people that way. So I had to find alternative hypotheses, but I was still working in a basement bar with no windows.

I wanted to test my new theory that, generally, the amount of alcohol consumed had no effect on the size of the tip.

I decided to work New Year’s Eve, which at that time went on until 2:30 in the morning. Drunk or sober, the tips were pretty much the same, although after 1:30 they were supplemented by all forms of contraband, which was not what I needed.

What good is control if you don’t get what you want? There is no barter, or like-kind exchange, when you are holding contraband and you really need toothpaste.

Woe is me. Logic had failed me.

But then, it’s hard to use logic to justify your existence as a bartender in a windowless basement bar.

Here’s the proof:

You can’t really stop people who are 52 years old and ask if, by chance, they knew whether their parents happened to be drinking in a now-defunct basement bar in Harvard Square with no windows nine months before they were born.

Alas, logic has its limits.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 22, 2022 | Featured, Personal

For my friends and me, life was abruptly changed on the after school athletic fields in the spring of our eighth-grade year, when all of our parents signed us up for dancing school.

My friends and I were all told it was a non-negotiable part of our education.

We were divided on the subject, until one of us confessed that in church he had recently prayed to God that he be allowed to live long enough to experience sex.

We found this to be reasonably compelling and it was sufficient to open the door for the rest of us to give in and accept the inevitable.

We had been given no previous training for this.

My preparation for dancing school was to wash my hair and then soap and rinse myself several times until I was squeaky clean, then do pull ups on the shower curtain rail in front of the mirror until I began to perspire and I couldn’t do anymore, in order to improve my physique.

Dancing school started at 4:30 pm. It was held in the middle school cafeteria at our all-boys day school. After lunch, all the tables were moved to one side, the chairs were placed side by side along opposite walls, and a piano was rolled into place.

Our instructors, Mr. and Mrs. Knot, were a husband and wife team who appeared to be in their 30s. The husband played the piano, smoked constantly, and showed no enthusiasm. We all liked him from the start.

His wife however was stern, and dressed in black high heels and a low cut black dress that featured her remarkable figure. From the start we had a problem. We couldn’t look at her, but we couldn’t take our eyes off of her.

Mrs. Knot would single out the tallest boy to dance with her. She would teach him the steps while the rest of us watched. We were then lined up with the girls from tallest to shortest and we could repeat their example.

Mrs. Knot soon showed the boys how they could politely change partners on the dance floor by tapping a boy on the shoulder.

One of the shortest boys in the class, who had big glasses, tapped Mrs. Knot’s dance partner on the shoulder in what appeared to be a shameless attempt to gain favor with his teacher. She appeared to approve, until they began to dance and she realized that her high heels and his height had placed his nose in her cleavage and his glasses were focused squarely on her breasts.

The girls were at least a head taller than most of the boys and, after a week or two, Mrs Knot announced a “ladies’ choice.”

The ladies’ choice turned out to be an extremely athletic event. The girls were choosing boyfriends but we didn’t know that.

They would slowly stand and walk toward their target, but if there was competition, they would pick up the pace and start running. There were times when two competitors, in an effort to get their boy and also to stop, would pile up and slide under the chairs where we were sitting.

The situation grew more mature. Later that spring, I had a girlfriend for almost a month, but I didn’t know that until she dumped me.

This was not unusual. Attachments were formed and broken in many cases before a boy even knew he had been going steady.

I was in my second relationship and didn’t know it until I was informed that it was over. I was told by a girl who I didn’t know that I had just broken up with a girl and that I was now available.

As the classes drifted into spring, the more adventurous girls would talk their parents into parties in the basement of their home.

They were all pretty much the same. They featured a record player and rotating chaperones to make sure nobody danced close during “Moon River.” The rule was stiff-arm dancing with visible open space between the dancers.

As the spring finished up, the chaperones and other parents migrated upstairs and gathered in the living room for cocktails. Occasionally, they would do sneak attacks or peek down into the basement to make sure the lights had not been dimmed or turned off and people were not dancing close to “Moon River.” They always claimed they were just making sure “the snacks had not run out.”

By summer, we had made friends with girls and even fallen in love and knew it.

Something beautiful had happened that spring. Nobody really knew what it was other than a transition, but it was beautifully woven together as a right of passage for everyone, including the parents.

The following spring, as upper-school ninth-graders, we would spill out of school at 4:30 pm and look in the windows of the cafeteria as Mrs. Knott waltzed her way through another dumbfounded eighth-grade class.

We had friends that were girls now, and we even knew enough to know we had girlfriends. I had even learned to do pull ups before the shower.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 8, 2022 | Featured, Personal

It is funny how a stranger’s aging face will never reveal the face of its youth. However…

A little less than a month ago, I went to a beautiful warm sun-drenched October wedding on the edge of a calm harbor in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

On the lawn, an hour or so before the wedding began, a small group of old men slowly gathered and greeted each other. Some had not seen each other for almost 50 years.

We had become friends long ago during high school, as a diaspora loosely formed by outcasts of various different New England schools. We had all been transferred or expelled from someplace, in several cases more than once, because of undiagnosed learning issues and/or an intransigent attitude, and thus had been prematurely released upon the world to get our education on our own terms with far less supervision.

No harm done. Most of us survived and had lived interesting lives of our own making and all of us had stories of our adventures along the way as we talked out on the lawn during that evening, or later on the phone. Nonetheless, we had bonded quite profoundly from our common experiences back then, and these stories and adventures defined who we believed we were.

As we told the stories about each other, the mask of old age dropped from our faces.

There was one friend who was not present as we rekindled old friendships and plowed through our memories.

The bride’s father had included in the program an “In Memorium” section that included those who had been lost along the way. One of our lost friends, let’s call him Brad, had been the bride’s godfather before his death.

Brad had been lost at sea years ago.

I didn’t know him as well as some of the others but I remembered, early one spring day, going down to the boatyard he used on Cape Cod, and watching him paint the waterline high on his boat to cover the approximately 2 1/2 tons of contraband that he expected to be bringing back from Jamaica a little later that year.

It was his custom to avoid returning by the Windward passage where he might be apprehended and instead sail far out into the Atlantic, then head north for an extended run, and then hug the shore as he traveled south back along the coastline in order to appear to be a tourist sailing down to the Cape from Maine.

He was a brilliant unflappable sailor.

One of his friends remembered how he had sailed back with him from Morocco, along with contraband, when Brad’s 37-foot deep keeled boat suffered debilitating electrical equipment failure. Brad then navigated without the aid of instruments, solely with a sextant, and expertly traveled down to the edge of the equator. As the sun came up one morning along the expansive horizon, he had watched “a thousand little squalls, each with rainbows beneath them in the sunrise” as Brad had navigated cross the Atlantic and hit his target, Antigua, perfectly.

Once freed from formal education, Brad was largely self schooled, but was well read in history, loved the Sherlock Holmes stories, and Shakespeare.

He was a wonderful and engaging companion. However, his freedom had not made him a saint. He indulged his ”weaknesses,” as he put it, sometimes at the expense of others as he enjoyed his world.

Early on, one of this group, who had become a lawyer, had been called upon to bail him out of a Jamaican jail where he had been held for some time.

He joked that he had been instructed to bring a little extra money to ensure his extradition, a fresh dry-cleaned white shirt folded on a cardboard back the way he liked it, and pressed pants, because within a half hour of his release they would both be drinking Remi Martin at a Jamaican bar.

We all knew Brad would not always be so lucky. He spent almost three years in Fox Hill prison in Nassau, and a year and a half imprisoned in Morocco, but it was the independence in him that we chose to remember.

No one knows for sure how he died.

He always had enemies in the trade, but he had also made good money doing commercial fishing off the New England coast. He disappeared offshore in the Atlantic during a squall off Cape Cod.

Nothing was ever found of him or his boat.

All the sailors in the conversation agreed that to leave no flotsam or jetsam behind was highly unusual.

The conversation turned from a general discussion of the squall to jokes about how improbable it was that the squall was really his cause of death.

Someone chimed in about how Brad had one time taken his boat to ride out a hurricane off Florida because being tied up at a dock would be more risky. However, when he had returned afterward, there were footprints on the ceiling of the cabin because his boat had rolled completely over during the storm.

Another friend suggested it was more likely that Brad had been hit by a freighter on the commercial trade routes that never saw him. Others who knew him well believed it was a settlement of old scores by others, and he had died with an anchor around his neck and his boat had been dragged back, repainted, and was now repurposed somewhere on the inland waterways, probably down south.

“No,” one of them chimed in. “He’s alive in Hawaii free of his enemies and debts.” One friend laughed as he peeled off toward the bar. “If he was alive, he would be here. He is the bride’s godfather. Remember how he had come to her high school graduation in a white suit? He took this stuff seriously!”

It is funny how old bonds of real friendship never break and how, when you see an old friend’s face, the young face can be reconstructed from a familiar smile or a remembered look. It is both a resurrection from the past and rebirth into the future.

Brad is still forever young for us even now, 50 years later, as we are for each other.