by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 17, 2025 | Featured, General, Humor, Law, Personal, Politics

When I started to practice law, Jimmy Carter was elected president. To avoid some unimaginable conflict of interest, he sold his family farm for peanuts. Since I retired from the practice of law 10 years ago, apparently the ethics have changed.

President Trump for his birthday last week gave himself a military parade, which which cost the American taxpayers approximately $25 million and tore up the streets of Washington.

Several news services have recently reported that since the early days of President Trump‘s reelection campaign he has made more than double his net worth, about $5.4 billion dollars.

In the past, I would’ve been horrified, but now my reaction is that it’s a shame I didn’t somehow make a bigger profit back when ethics prohibited me.

Back during those ethical times I would preach to the lawyers at my firm that the easiest way to check your professional ethics is to ask yourself if what you were about to do would be embarrassing if it would become a headline in the New York Times. If so, don’t do it.

President Trump has re-organized and turned upside down the professional ethics of the presidency and the ethics I was used to. Everything unethical or untrue that Trump has done now is routinely front page headlines on the New York Times, which nobody reads anymore.

I have gone back to thinking about how rich I would be if I’d taken on cases that I ultimately rejected long ago because of ethical concerns.

Consider the amount of money I could’ve made if I had taken that case long ago of two Hindu businessmen who came into the office and told me they wanted to incorporate (for personal liability reasons) an ongoing business that provided Hindu Americans a chance to bury their families in the Ganges River for about $5,000 per loved one.

They told me that the contract that they offered guaranteed that the loved ones ashes, with which they were entrusted, would be respectfully sent to the Ganges, a boat would be hired as well as a videographer to make a movie of the ceremony as the ashes were transported in a beautiful urn, and a man rowing the boat out in the Ganges would be filmed opening the container and emptying it so the ashes were visible as they were were gently poured into the river.

The $5,000 would be collected in exchange for the video of the ceremony.

I will admit I was intrigued by this novel, religious practice and I asked about the heavy cost of the procedure and the profit they were making per contract.

Without batting an eye both businessmen looked at me and said it was about 95% profit. I asked them how could they possibly make such a profit and they answered: “We send everyone the same video.”

If you’re using the same video and you are making a 95% profit you certainly don’t have to be greedy. You could include a beautiful hologram of the soul rising from the Ganges and fluttering off into reincarnation.

Also they completely missed the opportunity for relics, swag, and real cool T-shirts.

When you include the total Trump’s family and political friends have made in the “pay to play” access and favors, which have included the opportunity to show your personal love and respect by purchasing Trump bitcoin and Trump Bibles, and such gifts as an airplane from the government of Qatar, no wonder Trump wants a third term.

I was so stupid I refused to represent the two Hindu businessmen, even though they generously offered me a free burial in the Ganges.

I could also have befriended the President by referring him to another client who I rejected. For a while, “viatical contracts” were easy money. Several people had the idea at the same time. During the AIDS epidemic several entrepreneurs were going into hospitals or hospices and offering to buy life insurance policies at about 10% of their face value from those who would soon die. There’s nothing illegal about that, but for me it didn’t pass the smell test.

There is some justice in the world. Once effective HIV treatment became available, they were stuck continually paying for ongoing life insurance policies.

I suspect that the Trump family has already seen the future of medical profit as is evident from the appointment of Robert Kennedy, Jr. and the future of TMD (Trump Measles Deterrent). This is not a vaccine. it is free and called “The Trump Blessing,” which is administered over a Zoom call after you buy some of the remaining overstocked Bibles that will become collectors items soon.

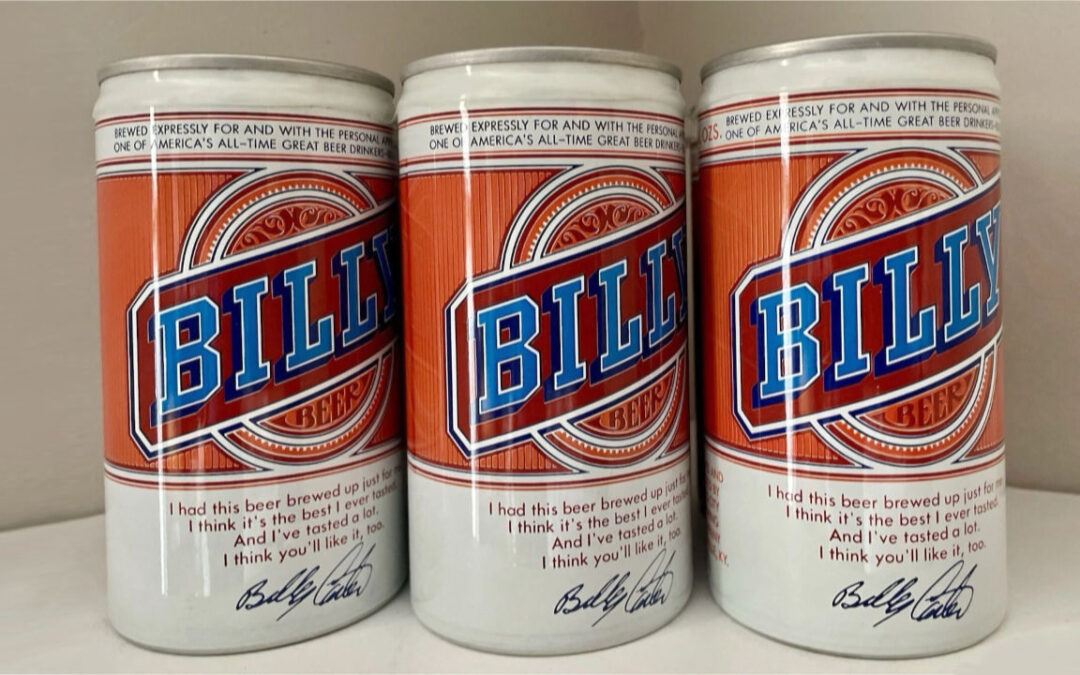

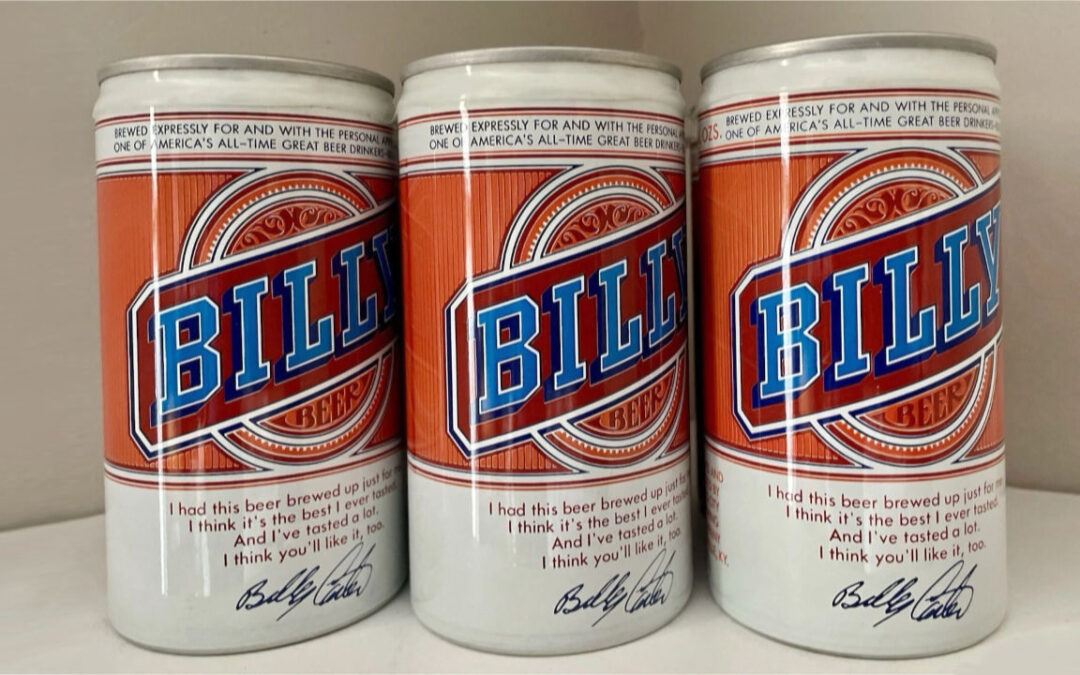

I think the only benefit Jimmy Carter received from his presidency was a gift given by his brother: a couple of cans of Billy Beer.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 18, 2024 | Featured, Humor, Law, People, Personal

As I have said before, I loved representing entrepreneurial business clients because they are crazy.

The little cases are always the funniest and the easiest to tell.

He was a general contractor who built big shopping malls and was always very gruff, extremely overweight and endlessly funny. He, his wife and I, became friends over time and my professional responsibilities merged into our friendship as we got to know each other.

After making a lot of money building shopping centers and stocking them with commercial tenants, he decided to design and build his own mansion. He bought two adjoining lots in a suburban cul-de-sac, and designed what his wife described as “a Las Vegas hotel — not only embarrassing but gauche.”

In his mansion, he determined that he wanted a large indoor fountain, as well as special toilets for his and his wife’s bathrooms. These toilets would protrude from the wall, but have no base onto the floor because he thought that was classier.

He had absolutely no sense of taste.

He battled with the architect who said that these toilets could not withstand his weight and were not classy just because they came out of a wall and didn’t have a base.

She succeeded in vetoing the lavish indoor fountain, but he won the battle in their matching bathrooms with the “extended toilet” from the wall, which had no connection to the floor.

I was his lawyer but we made each other laugh. As I was thinking back on him, I remembered defending him in a lawsuit many years before he built the mansion. He had put a roof on a tenant’s building and the tenant had decided to represent himself because he thought he knew everything about construction and could litigate better than any lawyer.

It was a little non-jury case to be tried in a packed courtroom full of lawyers and clients waiting for their cases to be called. Trying a case in a court at this level is like litigating in a circus tent a head on collision between clown cars — particularly if a defendant or plaintiff comes to represent themselves. The judges at this level have a rotating docket consisting each day of either misdemeanor, criminal, petty civil or traffic court.

I knew the judge socially. He had developed a sense of humor after too many years presiding over these petty cases and traffic court.

The plaintiff in this case argued that the “neoprene” roofing materials had been inadequate, and he was going to be his own expert witness to prove it. The plaintiff was a buffoon who didn’t know what he was talking about. It was a little case that would cost more to try than settle. The client decided to try it “on principle,” which is always a problem. He told me, “I don’t care if you win or lose, just make me laugh.”

I decided to go for broke. After the plaintiff announced that he wanted to be his own expert witness, I decided I would cross examine him on his qualifications before the judge ruled on whether he could be considered as an expert witness on roofing materials.

I asked him if he knew of the latest advancements in “neoprene” roofing materials. He clearly was uncertain but proclaimed he did. I had him hooked. I carefully asked him if he had ever heard of the new “Neofeces” roofing materials.

He said that he had. I spelled it out for him so he could be certain. He cautiously said he was certain.

So now I was crossing him on Neo (new) feces (shit) roofing materials. Clearly you could feel the courtroom saw entertainment in its future.

I asked him if it bothered him professionally that “neo-feces“ was still regrettably not yet odor free. He claimed it did not. I asked him whether he agreed that double-ply toilet paper was considered sufficient for the removal of “neo-feces.” The courtroom rustled as those watching started to follow the tightening of the noose.

After one or two more questions inquiring about the benefits of “neo-Feces,” I paused between the two words and the courtroom started to laugh a little but the witness did not. At this point, the judge stopped me to preserve order in the courtroom and instructed me that I had made my point and had “won the pot with a royal flush.” This was appreciated by all those still waiting to try their cases, as well as the backbench court watchers.

About a month after my client had moved into their new opulent mansion, I got a call from my client’s wife at around 11 o’clock on a weekend night.

She started the conversation by saying that I must come over immediately because she could no longer talk to her husband, who was presently lying on his back on his bathroom floor laughing hysterically.

Apparently, after a night of much beer and football on the super wide screen, he had sat down on his toilet and it had broken off, and he kept slipping and could not stand up because there was water shooting all over the bathroom. I told her I would contact a plumber to turn off the water and then I would be right over.

I asked her, “How bad was it?” She paused on the phone for one second and then just said, “Let’s put it this way, the goddamn toilets he wanted didn’t work, but that’s okay cause he got his goddamn fountain!”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 21, 2023 | Featured, Law, Personal, Politics

Abraham Lincoln famously said, “You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time.”

Lincoln’s quote applies to the voting public as well as trials before a judge or jury.

Former President Trump appears to be trying to win his legal cases with political arguments. He cares little about judges, but is determined to win an election, in order to pardon himself or have another Republican pardon him if he doesn’t run. Trump is leading in the polls, so this should be easy for him to do.

I learned how to do this from a chicken.

Years ago, I represented one defendant of four that were accused of stealing trade secrets that were provided to the lead defendant who allegedly included them in a patent for software designed for huge construction projects.

The plaintiff was a self-taught computer programmer. He was represented by a prominent New York patent firm.

The lead defendant was represented by a large Chicago law firm, which had contracted for the entire floor of an NYC hotel for the two month trial. The four trade secret defendants were represented by separate individual lawyers. I was one of them. The case was tried before a jury in the federal court in Manhattan.

I liked my client. I believed in his innocence after watching how he lived. Over the two years of depositions and trial prep, I became convinced of his innocence.

He had gotten a scholarship to college as an athlete. He struck me as a fellow who played hard, but he played by the rules. He was remarkably oblivious to how personal impressions shape jury decisions, perhaps because he was so straightforward.

The large Chicago firm gave the opening statement for the defendants that ran for a day and a half. They kept open every possible defense available and there wasn’t a defense that they didn’t like. One juror went to sleep but the lawyers seemed too busy to notice.

The other four defendants, the trade secrets defendants, each argued in their openings for at least two to three hours each, except for me.

As I watched those opening statements, I abruptly changed my strategy given the jury’s reaction to the openings.

I told the jury my opening statement would be no more than 15 minutes and whenever this trial ended, my closing summary would be no longer than 15 minutes and they would find that my client was not guilty.

I told them a little about my client and his little company, and then I sat down easily within the 15 minutes I had slotted for myself.

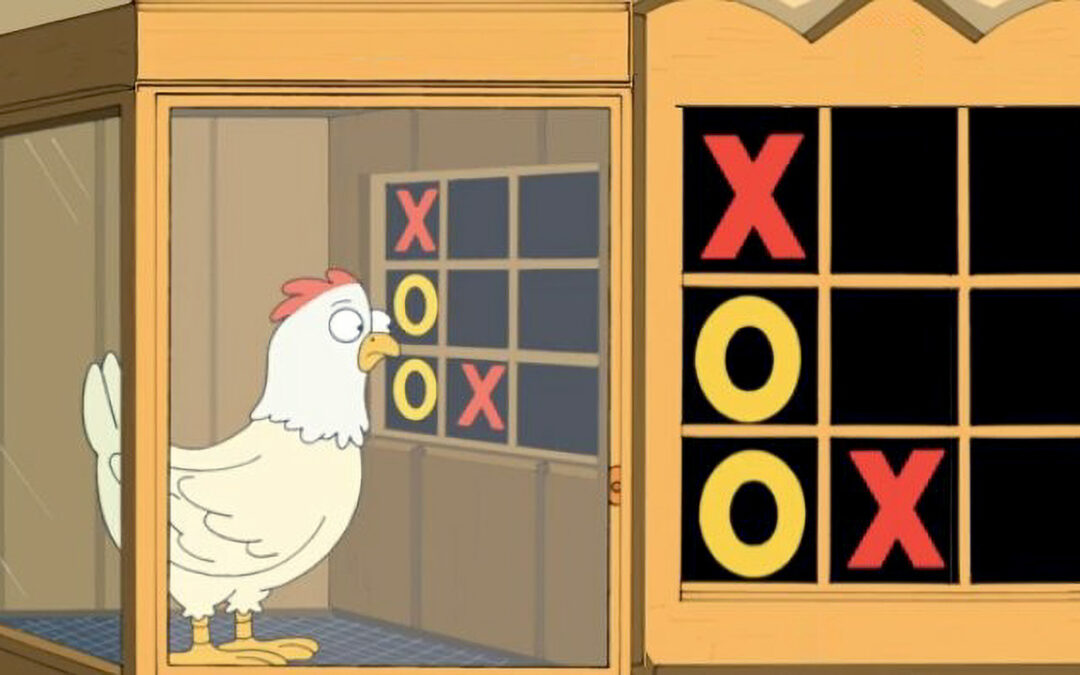

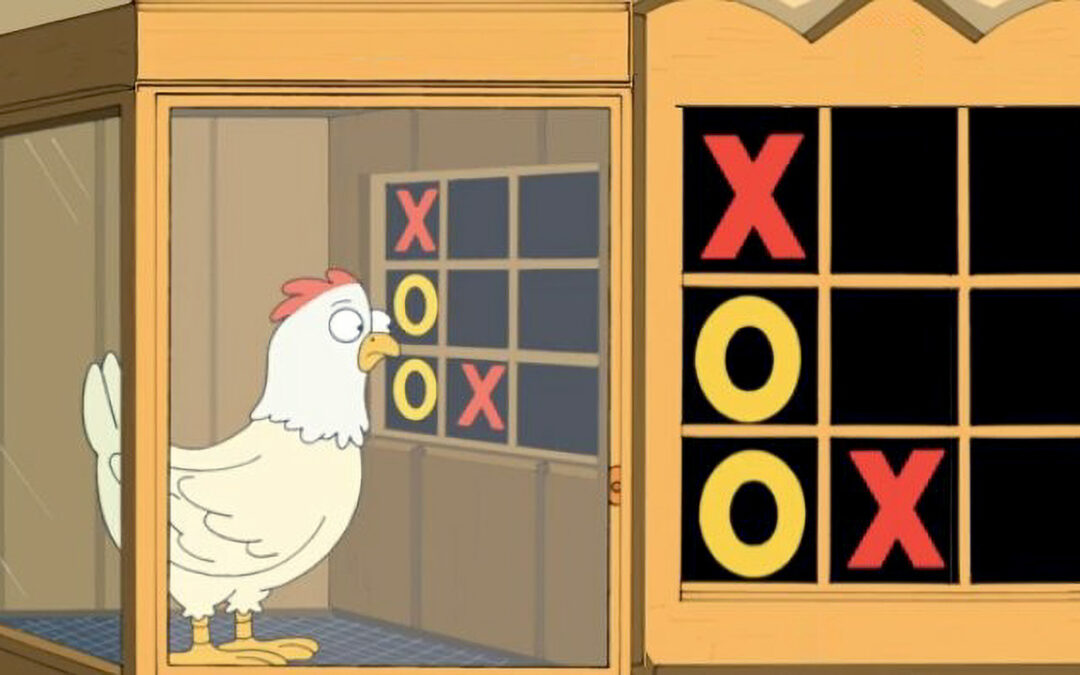

Every day of the trial, all the lawyers for the defendants went to lunch in Chinatown, which was right behind the Federal Court in Manhattan. The restaurant we went to had two attractions: 1) the dancing chicken, and 2) the chicken that would play tic-tac-toe against you.

You put the coins into the slot, and out would come the chicken. It would stare at you until you made your first move, tapping on the tic-tac-toe board that was on the glass that separated you from the chicken. An “X” would appear. The chicken would then make its counter move, pecking its choice of position, where an “O” would appear.

Even though all of the defense lawyers went to eat at this Chinese restaurant, none of them played this game because, I’m convinced, they didn’t want to dim their genius by losing to a chicken. That is certainly why I didn’t play against the chicken.

This was a serious chicken. The chicken was really good. It was so good that years later when the chicken died it got an obit in the New York Times. It was all a con job, but everyone was captivated by it. The chicken was given a signal where to pack in order to get fed, and thus peck the correct box.

As the trial progressed, I grew more worried that this case was so complicated that nobody understood it. Worse, now there were at least three jurors who were dozing off.

I became convinced that the defendants would not be considered individually. I feared that they would be lumped together with the patent defendent, and the smaller trade secret defendants would be found guilty as well, including my client.

When it became my client’s turn to testify, he came to town and, before he took the stand, we went to the Chinese restaurant. However, on the way to the men’s room, when I wasn’t looking, my client challenged the chicken.

The lawyers stopped eating and watched my client as he lost to the chicken about an hour before he was going to testify. After he lost to the chicken, everyone was remarkably quiet and nobody seemed to be eager to talk to me.

In a funny way, the loss to the chicken confirmed for me my client’s integrity and it fit quite nicely into my new strategy.

When I put him on the stand, I abandoned my prepared outline and changed gears. I kept it short, simple and direct. I flat out asked him whether he had stolen anything that became part of this purloined patent. He was surprised that I had changed our planned testimony. He replied instinctively without reservation and answered no.

I then announced that was the only question I was going to ask and then I sat down. The plaintiff never cross-examined him because he was small potatoes, and there wasn’t much testimony to cross examine.

Thereafter, I also changed gears and cross-examined the plantiff’s patent expert witnesses about the trade secrets case, which they knew nothing about. They cared only about the patent, not about the claim of trade secrets theft.

I asked each expert witness the same question: “After the years that you have put into preparation for your testimony, did you find any evidence that convinced you of my client’s guilt?” In each case, they shook their heads and answered no.

The other lawyers thought I was crazy and looked down at their papers in an effort to avoid laughter.

I added insult to injury by dramatically turning to the court reporter and saying that I wanted a copy of the answer to my question and, in each case, the court reporter nodded and I would get a couple of pages of transcript the next day.

After almost two months of trial, we went to closing, and again all the defendants gave days of closing arguments. When it came to me, I put my watch on the lectern and I looked at the jury and said, “Remember my promise of almost two months ago? I am going to give you a closing that will not exceed 15 minutes.” Then I quoted from the transcript pages that I had requested from the court reporter, the answer from each expert witness that stated they had found no evidence relating to my client.

Back then, during breaks, everybody could smoke cigarettes in the hallway. I got to know the plaintiff because he smoked a pipe and I smoked cigarettes, so we shared matches and talked.

He saw what I was doing and actually appreciated it. He would always start off after we inhaled and then, with a smile, would laugh and say, “smoke and mirrors.”

All the other lawyers waited three days for the verdict. I had to catch the train back home because I had a small trial starting the next day. After three days, the jury came down hard against all of them, but acquitted my client.

A day later I got a faxed letter from the plaintiff. He had won big, but he still sent me a letter with a smiley face and “smoke and mirrors — congratulations.”

So much of the time, appearances are more powerful and persuasive than the facts. We will see if Trump “fools the people” in the end.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 2, 2023 | Featured, Humor, Law, Personal

I want to tell you about a special award I created and bestowed upon myself.

The Stuffed Shirt Award.

Usually, awards are to celebrate accomplishment — with plaques or statuettes and a large party where such honors are bestowed, like The Oscars and Tonys, or Lifetime Achievement Awards.

However, there are also awards that single out questionable distinction.

For example, the Darwin Awards are annually given for “improving the gene pool.” This is deceptive because it only honors an act so stupid it often ends with the demise of the honoree and is thus given posthumously.

One of the early Darwin Awards went to a gentleman who put a jet rocket engine in the trunk of a Dodge Dart, and died after hitting a vertical cliff wall about 400 feet above the highway.

Somewhere between these two extremes lives the Stuffed Shirt Award.

The Stuffed Shirt Award is typically reserved for professionals, specifically professionals who think too highly of themselves.

The award requires a public demonstration of perceived self-worth, which must be 1) noticed by at least one other person and 2) leads to a moment of genuine disbelief demonstrated by a visible shake of the head by the observer.

An example would be the senior partner at a large law firm I was up against in NYC who FedExed his dry cleaning home to Chicago because he didn’t like the way the dry cleaners in New York City did his shirts.

Hence, the name of the award but the award is not about shirts alone. Here’s how I qualified:

I was fortunate when I first started my law firm back in 1990 to be representing a very large electrical contractor who routinely did huge jobs, such as the electrical work on Coke ovens at Bethlehem Steel, and also the Ted Williams Tunnel, which was towed in 12 sections by tug boats up to Boston from Maryland.

The case covered the construction of a subway system in southern Maryland leading from to Washington DC. There were loads of defendants.

It was an arbitration. The judge and everyone involved had agreed it should be held at the empty yet-to-be-opened subway station where the work had been done. I loved the idea because the subway station “courtroom” was my Exhibit A.

The Maryland State government had many branches and each had different lawyers representing them who were “in-house counsel.” I, however, was an independent lawyer with a big client and I was my own firm and I was damn proud of it.

I had all the makings of a stuffed shirt. All I needed was an event that would lead to a “genuine moment of sincere disbelief and the shake of the head” to be a competitor.

My client and I were seated in the middle of several tables pushed end-to-end, with all the opposing lawyers spread out on the other side.

As the arbitration began, each lawyer introduced their agency. They started at one end of the table, announced the agency, and then announced they were “in-house counsel“ for the agency.

The introductions went from left to right and finally ended after perhaps 15 minutes. None of them were independent counsel. They had all introduced themselves as “in-house counsel.”

Then it was my turn, and I decided that I needed to distinguish myself as an intimidating big shot lawyer.

I paused. I straightened the evidence books and the trial notebooks on the table, leaned forward in my chair, and announced:

“I’m Bob Bowie. Outhouse Counsel.”

My effort at intimidation had fallen short. The laughter rose and renewed several times, echoing in the large empty building. Thereafter, throughout the case, my fellow lawyers would periodically slap me on the back and say how funny I was.

I won the case but had dodged a bullet. There was no plaque or statuette. There wasn’t a celebration. They didn’t even know I had qualified for a Stuffed Shirt Award. To my amazement, this was the start of several long friendships.

Whenever I see them, they are quick to remind me that I am still their favorite “outhouse counsel.”

Self-importance can be like a hot air balloon.

It’s beautiful to see the world from an exulted height but returning back to earth may be its unexpected gift.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Sep 27, 2022 | Featured, Law, Personal

Back before I started my business law firm in 1990, I was hired by a respected personal injury law firm to try their bad cases as well as the “impossible cases.”

So, what is an “impossible case”?

Here’s an example: I tried a case where two motorcyclists in Western Maryland collided head on coming around a turn and, along with lots of broken bones, both drivers got amnesia so neither could testify who crossed the center line and, of course, there were no witnesses.

Midway through the trial, which came down to the inferences of skid marks and comparisons of the two front wheels, the case was settled when the insurance companies came to their senses and decided to pay the litigants instead of the lawyers.

No one will ever know who crossed the center line and so no one will ever know what the truth really was.

It was one of those “impossible cases.”

Over forty years ago, there was one impossible case I tried that still troubles me.

It was just a simple red light/green light case. The high school girl who I represented was listening to the radio while driving late one December afternoon down Eastern Avenue where it crosses Gusryan Street in eastern Baltimore.

As the girl approached the traffic light at the intersection, she claimed her light was green, so she drove through the intersection and hit a car. The driver of that car and his three passengers claimed his light had changed to green as he approached the intersection, so he kept up his speed climbing the little hill and got hit under the stop light at Eastern Avenue.

Both drivers and the passengers in the man’s car all claimed the other car had gone through the red light and caused the accident. It was a fine example of a classic “he said/she said” impossible case.

I wanted to win the case and there wasn’t much to work with, so I decided to use cross examination to question the credibility of the driver and his passengers’ testimony and use it against them.

I asked the judge to sequester each of the witnesses in the car so that they could not talk to each other before or after each went on the witness stand to answer my cross examination.

I asked everybody in the man’s car the same two questions: “Did you yourself see the light change to green before your car went through the intersection?”

And then I asked the passengers, “Isn’t it true that the driver is your boss?”

Both the driver and all the passengers answered yes to both questions.

I set the trap and it snapped shut.

At the close of the case, I asked the jury what is the likelihood that all four people in that car were watching exactly at the moment that the light changed from red to green? And then, “Wasn’t it true that the reason that all the passengers in the car were allwatching when the light turned green was because the driver was their boss?”

It was a magic trick.

It is the trick I play on myself neatly everyday but rarely do I get caught. It pits my belief that it is not okay to imply the truth and twist a situation just a little bit against my need to win.

I won the case, but the logic doesn’t hold.

After the jury came back, the boss came over to me. He had just lost the case but there was no anger. He held out his hand and congratulated me. “You did a wonderful job for your client but I do know in a way that you can’t. I know the light was green. I saw it.”

I saw it in his eyes.

It was no longer one of those impossible cases. I had made a mistake.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Feb 18, 2020 | Featured, Law, News, ONAJE, ONAJE Update, Operetta, Plays, Poetry

Okay, I may have a problem. I am a recovering lawyer and now aspiring playwright and poet. Is it possible that I miss time sheets? “Every six minutes” for a lifetime?

People used to say: “You are what you eat,” but what if you are what you “do” or have done?

Maybe I’m getting worse. At the law firm, I made a rule that if anybody could finish a story that I was telling I would stop telling it.

Now I don’t care. If I can get a second laugh or even a third from the same story I will repeat it, again and again. (And I’m going deaf so I’m the only one who doesn’t have to hear it.) It could be senility. It could be I’ve lost any sense of embarrassment, but it definitely demonstrates no merciful memory loss, at all.

The other thing is, even in retirement I must “work.” I have grown even more intolerant of delay because everything I’ve written should be on stage by now! Damn it!

What has happened to me?

In the past year, I have written or rewritten three plays. One (Onaje) has been produced in New York, two will be produced in New York (Vox Populi, for which I wrote the libretto, and The Grace of God & The Man Machine). Another, The Naked House Painting Society, is looking for a home.

Yes, I used to be impatient as a lawyer but now my stuff is not produced fast enough? Do I still need litigation? The need to measure work on massive conflicts in tight building blocks of measured time along with a new project have made me afraid.

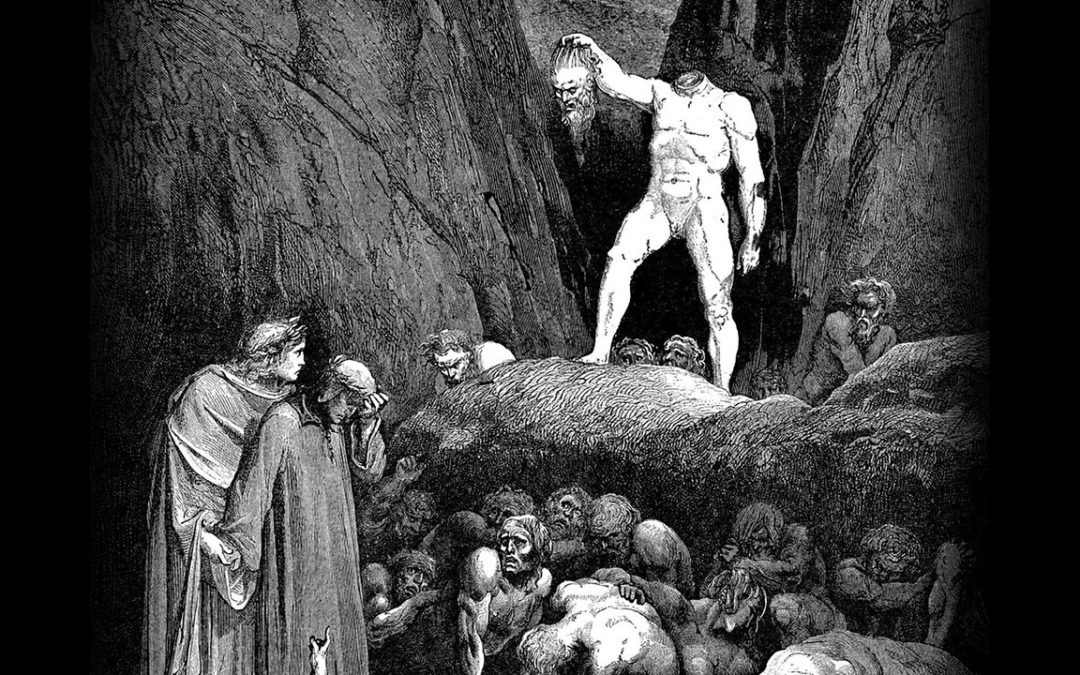

I have started working on a poem based on Dante’s Inferno. Dante’s Inferno has 34 cantos and 23 six-line stanzas in each canto. That in itself was my wake-up call. How sick is this?

The law can definitely create “delusions of grandeur.” Might it also imprint the structured, ordered, anal impact of time sheets?

Is it now that I require 34 cantos and 23 six-line stanzas in each canto? Seriously? But I haven’t given into it yet, I think.

Still, as I started the Prologue and began to “write about what I know,“ I found a schizophrenic litigator’s theme begging for harmony. This is how it starts:

Prologue

With first light, or birth, or perhaps before/

And maybe after, comes the dialogue:/

The debate in the mind. Waves on the shore/

Each overriding the last. No monologue./

Two nagging voices in constant conflict./

One “as doubt“ the other “as hope,“ both spent/

Bickering on some path I did not pick/

Living the daily schedule of events/

As I wake and wonder where each day went:/

The debate in the mind. Waves on the shore/

Each overriding the last. What event,/

What plea, what prayer from my central core,/

What keeper of my life long travel log/

Can cure me of this endless dialogue?/

I start with a sonnet? How sick is this?

T.S. Eliot said:

“evenings, mornings, afternoons,/

I have measured out my like with coffee spoons;”/

And the poor man was just a banker.

Still, it will be funny and too long for me to repeat, so that may be progress.