by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 18, 2019 | Featured, Personal

I’m extremely fortunate to have had a class with Elizabeth Bishop, who was one of our great, late 20th Century poets. She taught us that any two poems, no matter where they are from, when placed side-by-side will cause an unintended contrast that will illuminate both. Once grasped, this is an eye-opening idea with endless potentiality for creative thought.

I grew up between two schools, two cemeteries, and Harvard Square. The Cambridge cemetery was relatively flat, had few trees, was wide open, and pretty much existed to hold the military dead of foreign wars and the citizens of that city. In contrast, behind the impenetrable black iron fence and gate of Mount Auburn Cemetery, spread a small and elite universe of acres of hills and valleys with shaded walkways and still ponds, as an arboretum of carefully preserved trees and as an aviary for local and migrating birds. These two cemeteries existed side by side divided only by a single two lane road.

As children we would freely ride our bikes among the military dead in the Cambridge cemetery but we were strictly prohibited from even entering Mount Auburn. It wasn’t a place designed for us. However, when the gates were open adults were permitted to walk among the graves and in its verdant splendor. Mount Auburn rested like a shared understanding of what a patrician heaven might be while the Cambridge Cemetery was a plebeian limbo.

When I visited after last Memorial day the Cambridge cemetery had rows and rows of flags. One at each grave. No one was there except a lone bagpiper striding along one of the empty roads. Unexpectedly, I could find only one flag in all of Mount Auburn and it was guarded by a wild turkey that had become domesticated by the place. There was a quiet urgency as groups of horticulturalists or birdwatchers clustered as they whispered observations to each other.

Miss Bishop, as she called herself, was right. The accident of the unintended contrasts caused by my time and location that day opened up worlds for me about the two cemeteries, about the living generation and the predeceased, as I walked between the four.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | May 7, 2019 | Featured, Law, Personal

Several years ago Professor Mike Millemann, on the left, contacted me to see if I wanted to help him fulfill a grant made to the University of Maryland Cary School of Law to teach law differently by using the theater.

We signed up Elliot Rauh, of Single Carrot Theatre and decided the class should write plays about prisoners who had been released from prison after they had been determined to be absolutely innocent after years of incarceration. One of those plays was about Michael Austin, at the center, who was imprisoned in Maryland for over 27 years for a murder he did not commit. He was freed through the brilliant legal work of Larry Nathans, Esq., of Nathans & Biddle.

Last week we got together again at Lexington Market in downtown Baltimore as a reunion of old friends to help Michael because Michael had just found out that due to a typo in his arrest record he was never exonerated and that has kept him from getting work. This will be resolved but the reunion between friends nonetheless was wonderful.

In Michael’s case, and in most of the cases that we turned into plays, the process was remarkably similar. On the first day of class we brought Michael in to meet the class and answer questions. He was calm, collected, and despite the injustice of his incarceration not angry but very wise. In prison he had perfected himself and along the way he had become quite a remarkable musician.

Throughout the following weeks of the semester, the first third of the class was used to do deep research on what went wrong and what led to his conviction. The class went through trial transcripts, records of an incompetent defense lawyer, and files of prosecutors that withheld evidence and a transcript recording of the judge that sentenced an innocent man to life in prison.

The second third of the class the students wrote the backstory, and in the third and final part of the class, Elliot Rauh taught acting and turned inexperienced law students into the actors of their own play which was performed before the law school.

Michael stayed with the class from the beginning. One of the students said that he should provide music for the play and he agreed. Another one of the students suggested that at the end of the play, Michael should leave his instruments behind and identify himself as the Michael Austin about whom the play was written. The audience gasped and some wept.

At first I thought this class might have limited value so we asked that the students provide a one minute clip to the people who had provided us the grant to state whether they thought the grant money had been used appropriately. I became convinced when one student faced the camera and said “I wrote the part of a defense lawyer who was unprepared, acted the part of the prosecutor who withheld the time card that would have exonerated him, and read the exact words 30 years ago when an innocent man was pronounced guilty by a state court judge in the circuit court of Baltimore city and sentenced to life and I have never been in a courtroom.”

At that point we were convinced that the class worked. People were learning from mistakes made before they were fatal. We taught the class for seven years and it was ranked as one of the most appreciated classes at the law school during that time.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 28, 2018 | FringeNYC, ONAJE, Personal

In the West Village of New York City, on October 13th at 7:00 in the evening, ONAJE opened as my first professionally produced play. I sat in the back, in a balcony with lights and sound equipment around me and watched the audience file in and take their seats. I gave the appearance of being calm but I was terrified.

I have been to opening nights for nine of my prior plays in the little theaters of Baltimore and I have learned there is an immediate courtship: the call offered by the actors at the beginning of the play and the audience’s response. You can feel it. It is confirmed with the first laugh but the commitment can also be felt in the early silence.

As the play unfolds, from the back of the theater, you can watch for physical movement, restless disengagement as evidence of the loss of commitment to a play. It can become contagious in the dead silence and then nothing can resurrect the play. Once you lose them, there is no getting them back.

My friends, the composer Christian De Gré and our producer Susan Conover Marinello, and I had been fortunate to have Tom Viertel as our dinner guest three weeks before we opened. Based on years of experience as a renowned Broadway producer, the founder of the Commercial Theater Institute, and director of the O’Neill, he told us a “no-intermission play cannot run more than 93 minutes” without the high risk it will lose its audience. There was no doubt in his voice. We took his advice. We knew he was right. I went to work cutting lines and shaping the script with four script reductions.

Opening night at FringeNYC was to be judged by a sold-out crowd as they rendered their verdict first in the dance of commitment as the play got underway and then after 90 minutes by the way they moved in their seats.

For me, knowing every line and the slightest modulations in an actor’s voice, the experience was, of course, different than an audience seeing it for the first time. The audience will be engaged until they’re not. The only measurement that is credible is how the theater feels and how the shadows in the seats sit engaged or start to move. That is the only language.

I could feel this audience’s early engagement and commitment to the play and surprisingly when I did, I started to daydream about the genesis of this project:

I am the oldest son. The oldest son of the oldest son of the oldest son, all of whom have been well-respected and distinguished lawyers, professors, and public servants. Although my father supported my love of storytelling, bringing me hand puppets from his travels and building me a little puppet theater so I could perform for my seventh- and eighth-grade classmates, there was no doubt my next step was to carry on the family profession of law.

While I dreamed of writing plays, I grew to love being a business trial lawyer. Before my father died several years ago, while I took care of him during his final years, he quite casually one afternoon looked at me and said, “I am very proud of what you have accomplished. I could never have started a law firm and succeeded in the way you have.”

Almost accidentally, he had released me to change my avocation to my profession. I soon retired and made a full commitment to become a professional playwright.

Opening night at FringeNYC was for me, unconsciously, like a flock of carrier pigeons released well over fifty years ago coming in to roost.

The last seven pages of the play runs 12 minutes to conclusion. I leaned over the rail and listened for the quality of the silence and looked down on an audience that did not move. They were engaged after 96 minutes, three minutes longer than Tom’s ultimatum. We had pushed the envelope but still survived.

The lights came down and there was a moment of silence, and as the actors came to their curtain call they were met by increasing and sustained applause. As the theater emptied out I saw many of my friends, some of whom had traveled from as far as California and Canada, as they walked to the stairs to exit past my door from the balcony.

I was not conscious at the time, even after I was welcomed by the audience and my friends, that like the characters I had written in ONAJE, after a long journey, I had finally come home.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 14, 2018 | Personal

For years and years, I practiced law and total strangers would stop me and say “Yer a lawyer, aren’t you?”

I mean, really!

It started about a year after law school when I was learning to be a litigator. I loved being a lawyer but now I’m retired and in recovery. Strangely, no one asks that question anymore.

What changed? What were they picking up on in the first place?

We all know the world through our five senses, so which of the senses lead me to be identified as a lawyer? I’m portly enough to be the mayor of a small town. I’ve got a voice perfect for broadcasting large sports events. I’m not one of those instant huggers. I bite my own nails and when these people identified me as a lawyer they were not all downwind of me.

When I walk down the street now, I’m waiting for people to recognize me in a new light. “Yer a playwright, aren’t you?” Come see ONAJE this October at FringeNYC and help make that dream come true!

Join me on this adventure at https://theplayonaje.com.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 15, 2017 | Featured, ONAJE, Personal

I write plays but I can’t act. My acting career ended shortly after an all-boys fourth grade Christmas pageant. I was a shepherd. I had one line that I had to speak to introduce Mary onto the stage. The music teacher had placed a wig on the class bully and handed him a plastic Jesus in swaddling clothes. In real life, the class bully had biceps in fourth grade and Elvis hair. I misspoke my one line. I said, “Come mither hairy!” I returned from recess bloody and a playwright.

Last weekend at an invitation-only reading for artistic directors and producers, my play “Onaje” was read at 300 West 43rd street in New York City. It was read by actors who make a living being actors. I was stunned by the uniqueness of their genius.

I am a recovering lawyer. While I practiced law, I had nine plays produced in little theaters in Baltimore. Although I was proud of them, I made no effort to have them performed professionally. When my play was given a staged reading in New York for the first time I worked with professional actors and was blown away.

The performance was scheduled for Sunday at 3 o’clock in a 30-seat performance space. The actors were sent the script about a week before the Saturday morning rehearsal in an apartment in New York. The rehearsal was, in essence, a read-through where Eric Reid, an accomplished actor and director from San Francisco, gave directorial instructions and the actors discussed their characters. The actors were all obviously capable but I was not ready for what I would see the following day.

There was another read-through which was to a large extent the blocking of the reading. All the actors sat in chairs in the black box theater against the wall until they were on stage, which meant they stood and went to the music stands in front of them and delivered their lines. There was a one hour break between that rehearsal and the performance. At the blocking rehearsal, the actors were still playing with their characters well I had a terrible thought that they had not had time to become fully familiar with the script and their characters.

I went off to a late lunch with Eric and returned to see the actors in their own village doing breathing exercises, sitting quietly or doing yoga. I had no understanding of how good they would be on stage.

The small theater filled the actors took their places and the reading began. I saw a transformation that changed my understanding of the art of theater. Somehow, they knew the people they will play in an intimate and unique way. Somehow, they knew each other and the interaction created a greater whole. The play was very well received and the script has been requested after I have had a chance to do some work on the text.

Afterward, the lights went on and the actors were people again and they merged with the audience. I stood in the back of the theater immersed in surprise by the evolution of the process and the sheer genius of those actors. Actors are unique beasts.

A central aspect of my play concerns the capacity of people to empathize with strangers. I realized as I stood there I had witnessed it by the transformation of actors so easily turning the written word into human beings.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 20, 2017 | Featured, HAA, Personal

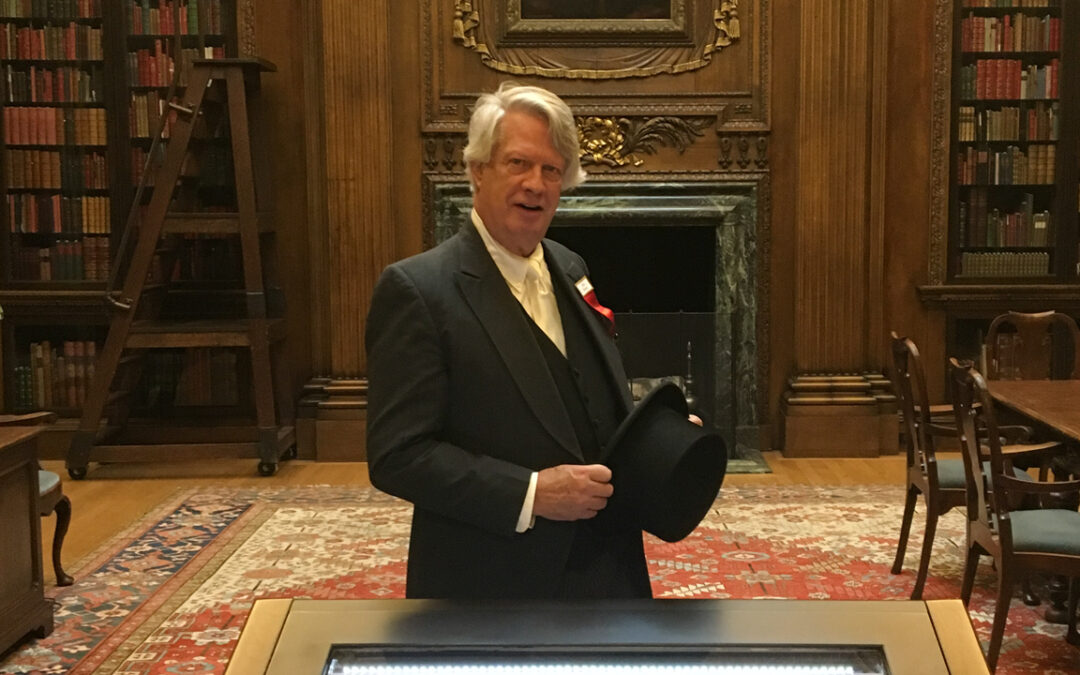

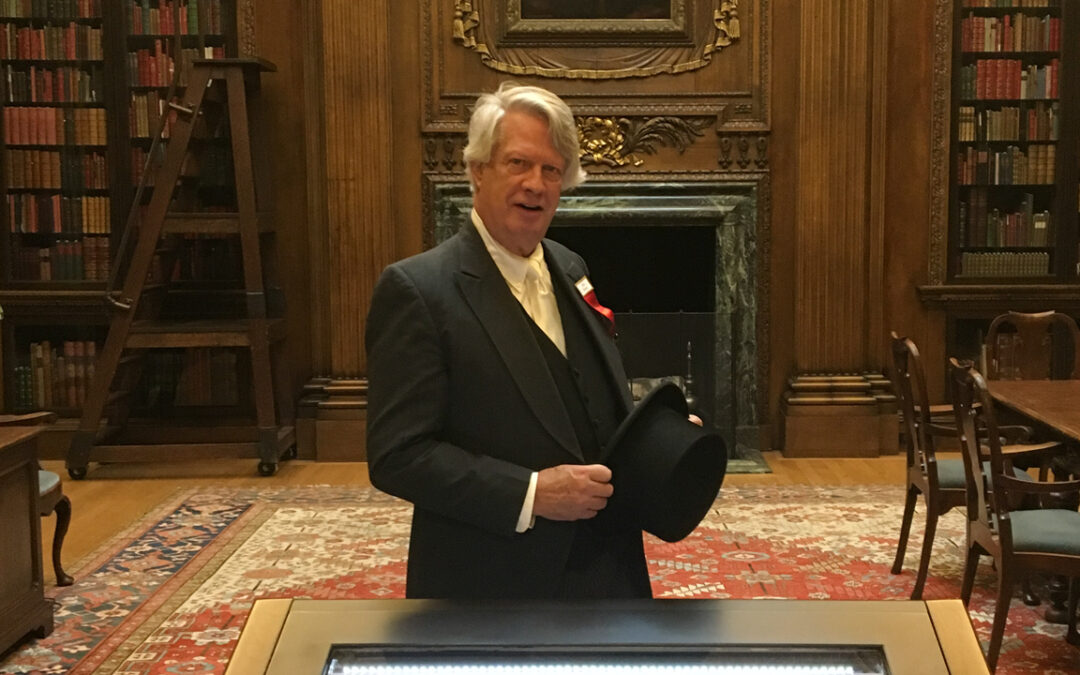

The “Costume” in my case was white tie and tails with a perfect black top hat. The “Set” was the Harvard graduation of last week. The “Plot”: Because of the custom of complete secrecy, I had been told only a few days before that I had been selected to escort James Earl Jones for the afternoon proceedings and to an honorees lunch at Widener Library after the morning ceremonies where he, along with several others, would be given an honorary degree.

Only last month I had seen his performance as the poet in Tennessee William’s Night of the Iguana at the American Repertory Theater and had read about his career, which started with his first appearance on Broadway in 1957 and spans 60 years on stage and screen.

After the honorary degree had been bestowed on him in the morning and those proceedings had ended, Mr. Jones would descend the stage, which is at the foot of Memorial Church, and march with his fellow honorees below the colorful flags of the graduate schools and the undergraduate houses, between the assembled throng of the thousands of applauding viewers to ascend the steps of Widener library and be directed to the periodical room where I would meet him, take his ceremonial cap and gown, unburden him of his framed honorary degree, and provide him with the refreshment of his choice. Then I would facilitate conversation among the other honorees before we took the elevator up to the lunch and thereafter back to the stage for the afternoon speech by Mark Zuckerberg and the closing proceedings.

I arrived early to Widener and made certain I knew exactly what my duties were and traced my steps from the periodicals room where I would meet Mr. Jones, through the elevator exit and entrance to the luncheon and ultimately the path we would take to get back to the stage and become seated for the afternoon proceedings.

But this was a very special moment for me, so I decided that I could entertain Mr. Jones by offering him a slight diversion from our proscribed path, to see the Gutenberg Bible in a private room which contains a portrait of Harrie Widener, for whom the library was named after he died on the Titanic a century ago. I confirmed that I could get into the room and because I was early I asked a solo passerby to randomly photograph me since the proceedings had not started and we were still allowed photographs before the event began. It would be my stage where I could watch James Earl Jones react to the surroundings I have offered him.

But my play went off script and the plot collapsed and, in fact, disappeared. The weather had been awful all morning with a steady drizzle and unexpected gusts of wind that sent the water across the crowds and the stage. Those being honored on the stage, although they were protected by a grand tent still suffering the blasts of wind and rain and the general chill of the morning.

As the proceedings broke up and the ceremonial march to the steps of Widener began, I assumed my position outside of the periodicals room to meet James Earl Jones, but as the others entered through the grand doors and were steered to their escorts there was no sign of him. After all the other honorees had entered and had turned over their robes and diplomas to their escorts, I went to one of the police officers guarding the ceremonies and started a flurry of walkie-talkie conversations in search of Mr. James Earl Jones. As the others took the elevator up to lunch, someone reported back that Mr. Jones had been worn out by the weather and the cold during the morning proceedings and had asked to go directly from the stage to his hotel room.

I never met him and I have only that photograph of the Gutenberg Bible in the foreground and the portrait of Harrie Widener in the background with a slightly rotund overdressed older man between them, and the realization that dreams can be memorialized in still photographs but plot cannot be deprived of action.