by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Mar 19, 2024 | Featured, Personal

Perhaps it was always just a place in time but, for me, it was the reality of my youth. Its boundaries were Harvard Square to the east, my home on Coolidge Hill with Mount Auburn Cemetery and Cambridge Cemetery to the north, two schools — Shady Hill and Browne & Nichols — to the west, and the Charles River to my south, but all of this was lived in the shadow of Harvard University during the Kennedy years and later the Vietnam War.

I was all in. I was a townie from birth. The athletes on the football and hockey teams were my rock stars, and the professors would take time off from the university to advise United States presidents who were graduates.

If you were fortunate to be admitted, I believed you were blessed for life and, starting with your freshman year, you would be offered an education unequaled anywhere else in the world.

It took me several expulsions, numerous worthless summer schools with worthless speed reading classes if you were a dyslexic, a condition that, for me, went diagnosed for years. All in all, it six years but I finally got through high school.

Anyway, I was determined to get into Harvard.

The Cambridge School of Weston, a progressive school in the suburbs of Boston, took me in but required that I repeat 11th grade and start working with Mr. Johnson, a trained reading teacher, who convinced me to finally take an IQ test and start fresh with the alphabet. When I asked, he smiled and he told me, “Yes, you can go to college.”

I immediately packed up my report cards and went to The Harvard admissions office, where I announced that my problems would soon be solved and I would be going to Harvard. I met with one of the admissions officers, Deke Smith, who went over my report cards, then looked up at me inquisitively and said, “You have never gotten anything better than a C+.” I was ready for him, and responded, “Well, they take 20 points off for spelling.”

He gently said that I would have to be president of my school, president of the literary magazine, as well as president of the New England Student Government Association, which encompasses all New England prep schools and their student governments. In hindsight, I’m pretty sure I was being offered the door, but I didn’t know that.

My senior year I went back to Mr. Smith and informed him that I had accomplished those three goals, and he looked at me sort of long and hard and apologized. “I did not mean to lead you on, but all we do here is read books and write papers. I don’t think you could survive.”

I applied anyway and was rejected.

I went off to a wonderful school in Ohio, left the campus dorms, rented an apartment in the town and went underground. In September of 1970, I was in a high-speed motorcycle crash, which killed the driver, my friend. I spent the next several months hanging from the ceiling in a pelvic sling in several hospitals until I ended up back in Boston and Cambridge, where I started to move again in wheelchairs and on crutches.

I had a moment of genius.

I went back to Mr. Smith at the admissions office and told him that I would not be able to go back to school that spring and hoped he would let me be a “special student” at Harvard so I could take one class and get credit for it when I returned to Ohio the next year.

He was shocked to see me again but remembered me. He recollected that I had surprised him the last time we met when I had accomplished all of his goals, including being president of the New England Student Government Association when, the year before, the Cambridge School of Weston was not even been a member. He reiterated also that I might survive with one class because, as he had said, “All we do here is read books and write papers.”

I got my student ID and realized I was inside the walls and I was living my plan.

I signed up for five classes, not just one, and told my mother that I would do all the research because I had nothing better to do than go to the library on crutches, but I asked her would she type my papers to avoid the spelling issues. She laughed and agreed and I went to work.

I did nothing but work and sleep and go to class and work for that entire spring semester. My one fear was the Blue Book hourly exams where I would have to write out my answers and reveal my spelling issues. I expected I would lose 20 points for spelling. When I got the Blue Book back, there were red marks all the way through it. But about two-thirds of the way in they stopped and at the very end, in red pen, was “You know your stuff but your spelling is atrocious. A-.”

I didn’t stop celebrating for a week.

After I got my report card, I went back to Mr. Smith and showed him I had gotten all A’s and B’s except for one C+, which then put me at least in the middle of the class.

He looked like a guy who just had his pants pulled down. I told him that I would be applying as a transfer student for admission the next year, then smiled at him and left.

He was defenseless.

Several months later, I got the fat envelope. I proudly walked into my parents’ bedroom as my father was reading in the late afternoon on the bed, and I told him I just got into Harvard. He smiled and offered congratulations then went back to reading. It was not his ambition, it was mine. I went to the kitchen to tell my mother and we, in fact, celebrated.

In 1973, I graduated with honors. Fifty years later at our 50th reunion, I met classmates who I had never met before and, only then, felt that I finally fit in, even though I did not qualify for admission. I thought I had justified my acceptance and graduation because I had loved that education so much!

That school gave me a chance that others wouldn’t. That school looked deeper into me than all the other schools, other than the Cambridge School of Weston, ever had. I felt for the first time I was one of them and worthy to be one of their classmates.

I live in Maryland now, as I have for years, but I really am very much still that Cambridge townie. Only weeks ago, when we were at Oriole spring training together, my son looked at me very seriously and asked, “Are you actually a closet Red Sox fan?“

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Feb 27, 2024 | Featured, People, Personal, Travel

After Ted Williams, Mohammed Ali and Bobby Orr, since I was a boy, I have been looking for heroes. There have been painfully few. The next generations have not, for me, been fertile ground.

I have just returned from a nine-day trip with a group of 15 friends through Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, and Tennessee. When I came home, I was shocked to learn of Alexie Navalny’s murder in a Russian prison.

I remembered that after Putin tried to kill him once before, he returned to Russia, only to be imprisoned yet again and ultimately murdered. He risked everything for the love of his country, its people and an integrity that is larger than his life. That is this old man’s kind of hero.

It wasn’t my objective but on the trip, I accidentally found the heroes like Navalny that I have been looking for.

For years, I have wanted to follow the “nonviolent” civil rights movement from the death of Emmett Till in 1955 up to when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed in Memphis on Aril 4th, 1968.

Yes, I had seen all the pictures, read the books and knew the dates and places as we all have. This movement started when I was in lower school and compounded until it arguably ended with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. when I graduated from high school in 1968.

It was all familiar to me.

But all the histories and research I had done became like reading the script of a play until I walked onto the stage where it had happened. Then I had no escape. It is different when you are surrounded by it. It is different when you become immersed in it.

The Delta blues surrounded us as we passed the crossroads where Robert Johnson is said to have sold his soul to the devil, then parked down the road near Baptist town to walk near where he had been laid to rest.

Much of the Mississippi Delta, our guide at the front of the bus informed us, is owned by eight families.

For hour after hour, the low flat land passes by, with row after row of cotton plants as far as the eye can see on both sides of the road.

Finally, we left the two-lane road from Jackson, Mississippi and traveled down a dirt road to a big house with five or six little cottages next door to it. These are the houses for the families of the tenant farmers who live there surrounded by their work, earning an annual income of around $8,000 a year — that is, before they paid their rent.

On the bus days later, I tried to better understand the famous 1957 picture of young Elizabeth Eckford as she tried to integrate Little Rock Central High School while screaming white people threatening her 67 years ago. Days later, I met her — now in her 80s — as she sat quietly in front of us and answered questions across from where it had all happened.

She said her parents were determined not to back down and they would not talk about it. She said it had taken her almost 40 years to come to grips with what had happened to her in that one day, and for the remainder of the school year, day after day, as she withstood catcalls and being shoved into lockers as she walked the halls.

That little girl in the picture with the sunglasses on, holding her books alone and determined, gives no evidence of the damage that was done to her, which had stayed with her for so long.

It was much the same with the picture I had seen of the cluster of black men in Memphis as they were all turning and pointing in unison as Martin Luther King, Jr. lay at their feet on the balcony of room 306 of the Lorraine Hotel. The hotel has been turned into a much bigger museum, with a plate glass wall preserving the hotel room that these men had left to talk to friends three stories below. It is now forever frozen with the shades all drawn.

I was not ready for 14-year-old Emmett Till’s final journey down from Chicago to visit family in Mississippi to the candy store where he whistled at a white girl. His two assassins had tracked him down three days later and extracted him at gunpoint from his relative’s house to be beaten beyond recognition and dumped in the river. Days later, he was fished out to be buried back home in Chicago in an open casket.

It all rushed at me hours later, when I found myself in the courtroom where the two men were exonerated in 67 minutes by an all-white jury who said they had a ten-minute Coke break to extend the deliberations. I was sitting in the seat of juror number six, right across from the witness stand where Emmett’s mother had testified in tears.

After I opened the news when I got home, Navalny’s murder drove me back to that trip.

I found heroes in many of the locations we visited. In the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, those heroes were in the records of the hundreds of lynchings, including many who could not be identified.

There are names we all remember, of course. They were committed to their country and to peaceful change despite the daily risk they might be killed. Martin Luther King, Jr., in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, said he could see the promised land, but perhaps he would not be there with them when they entered it. Soon thereafter, he was killed.

Medgar Evers, who was shot from across the street at midnight, had trained his children to run to the bathtub and hide whenever they heard gunshots, because it was the only place they might be safe from a high-powered rifle.

Medgar Evers was killed by a high-powered rifle bullet that went through him, through the front window of his living room, through the wall of his kitchen, and then lodged in the refrigerator.

These people died to advance the cause of freedom. Let’s remember them as we move toward an election that could determine how free we really are.

The night I returned, after I unpacked and turned out the light and set the alarm for an early breakfast, I thought about the people who I had met and the surroundings that had given old history a new life. I went to sleep thinking of those people as little candles where I could warm my hands, little flickering lights burning in the dark.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Feb 13, 2024 | Featured, News, Personal, Shorter Stories Book

Thanks to all who have been following my posts over the years, and for all your comments, support and encouragement.

Very soon I will be putting out a new book that collects some of my favorites of these stories, focusing on people and relationships (and trying to avoid politics).

It’s called “The Older You Get, the Shorter Your Stories Should Be.”

I’d like to ask a favor.

I’m hoping to use some quotes from my readers to help market the book, but I want to make sure I have permission, so I’ve set up a form here:

https://robertbowiejr.com/book-preview

If you have any thoughts or recollections to share, just a sentence or two, please weigh in — and be sure to let me know if I can reprint them.

To jostle your memory, that same form will take you to a sneak preview of the book’s first few stories. I hope you’ll enjoy them.

I’ll also keep you posted on the upcoming book launch.

(If you know anyone else who might be interested, please pass along that URL.)

Thanks again. I hope you will contribute!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 21, 2023 | Featured, Law, Personal, Politics

Abraham Lincoln famously said, “You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time.”

Lincoln’s quote applies to the voting public as well as trials before a judge or jury.

Former President Trump appears to be trying to win his legal cases with political arguments. He cares little about judges, but is determined to win an election, in order to pardon himself or have another Republican pardon him if he doesn’t run. Trump is leading in the polls, so this should be easy for him to do.

I learned how to do this from a chicken.

Years ago, I represented one defendant of four that were accused of stealing trade secrets that were provided to the lead defendant who allegedly included them in a patent for software designed for huge construction projects.

The plaintiff was a self-taught computer programmer. He was represented by a prominent New York patent firm.

The lead defendant was represented by a large Chicago law firm, which had contracted for the entire floor of an NYC hotel for the two month trial. The four trade secret defendants were represented by separate individual lawyers. I was one of them. The case was tried before a jury in the federal court in Manhattan.

I liked my client. I believed in his innocence after watching how he lived. Over the two years of depositions and trial prep, I became convinced of his innocence.

He had gotten a scholarship to college as an athlete. He struck me as a fellow who played hard, but he played by the rules. He was remarkably oblivious to how personal impressions shape jury decisions, perhaps because he was so straightforward.

The large Chicago firm gave the opening statement for the defendants that ran for a day and a half. They kept open every possible defense available and there wasn’t a defense that they didn’t like. One juror went to sleep but the lawyers seemed too busy to notice.

The other four defendants, the trade secrets defendants, each argued in their openings for at least two to three hours each, except for me.

As I watched those opening statements, I abruptly changed my strategy given the jury’s reaction to the openings.

I told the jury my opening statement would be no more than 15 minutes and whenever this trial ended, my closing summary would be no longer than 15 minutes and they would find that my client was not guilty.

I told them a little about my client and his little company, and then I sat down easily within the 15 minutes I had slotted for myself.

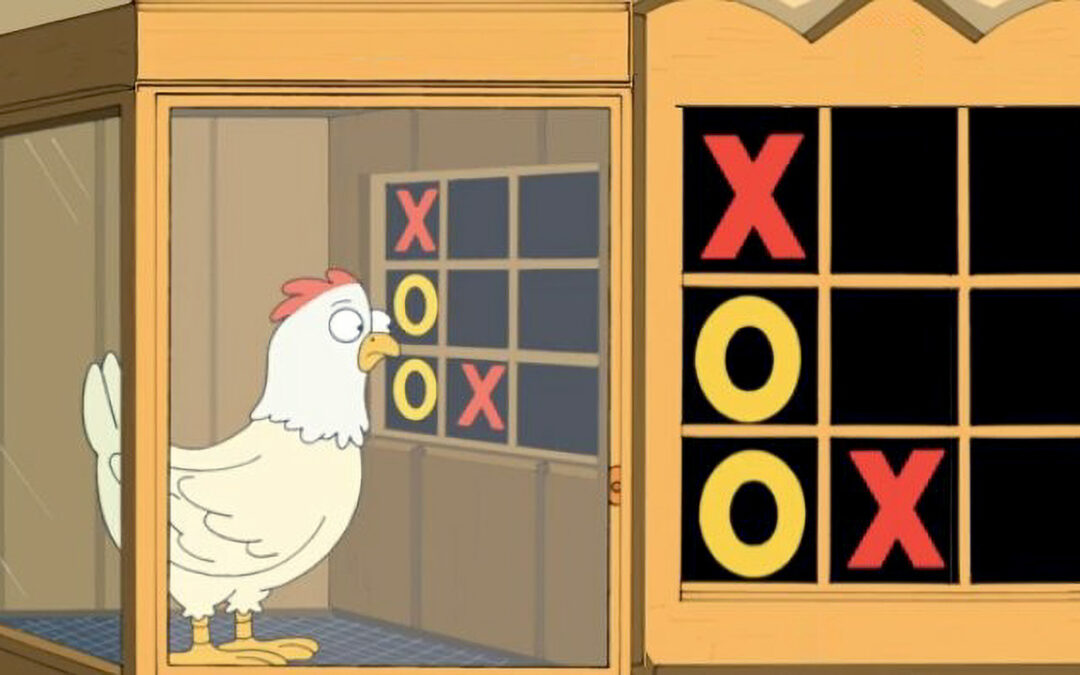

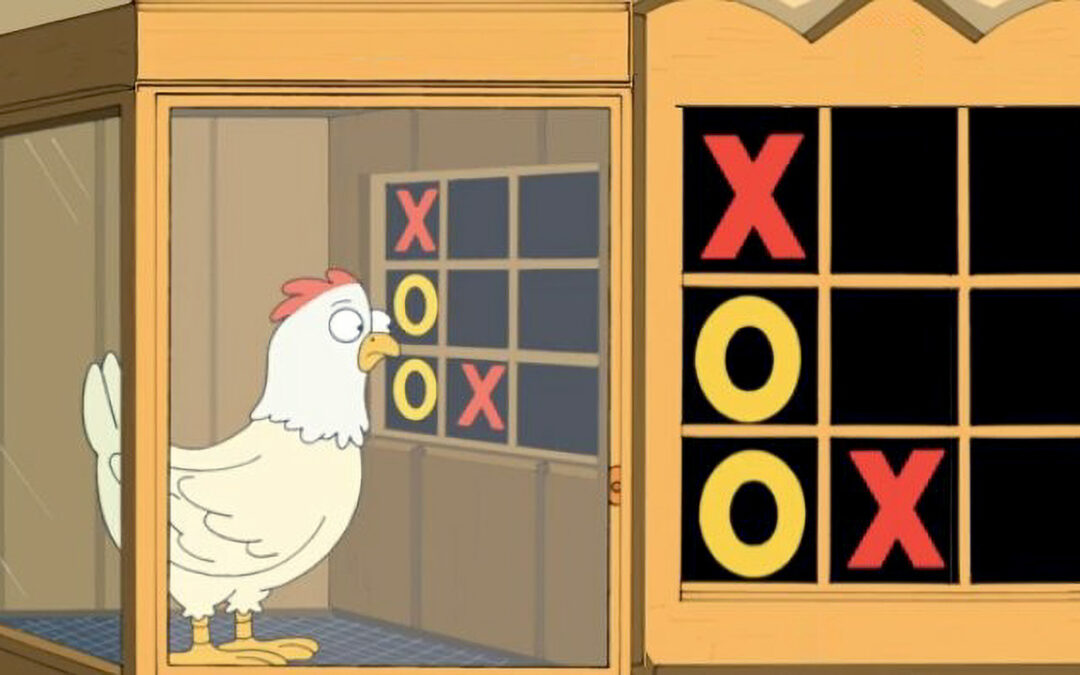

Every day of the trial, all the lawyers for the defendants went to lunch in Chinatown, which was right behind the Federal Court in Manhattan. The restaurant we went to had two attractions: 1) the dancing chicken, and 2) the chicken that would play tic-tac-toe against you.

You put the coins into the slot, and out would come the chicken. It would stare at you until you made your first move, tapping on the tic-tac-toe board that was on the glass that separated you from the chicken. An “X” would appear. The chicken would then make its counter move, pecking its choice of position, where an “O” would appear.

Even though all of the defense lawyers went to eat at this Chinese restaurant, none of them played this game because, I’m convinced, they didn’t want to dim their genius by losing to a chicken. That is certainly why I didn’t play against the chicken.

This was a serious chicken. The chicken was really good. It was so good that years later when the chicken died it got an obit in the New York Times. It was all a con job, but everyone was captivated by it. The chicken was given a signal where to pack in order to get fed, and thus peck the correct box.

As the trial progressed, I grew more worried that this case was so complicated that nobody understood it. Worse, now there were at least three jurors who were dozing off.

I became convinced that the defendants would not be considered individually. I feared that they would be lumped together with the patent defendent, and the smaller trade secret defendants would be found guilty as well, including my client.

When it became my client’s turn to testify, he came to town and, before he took the stand, we went to the Chinese restaurant. However, on the way to the men’s room, when I wasn’t looking, my client challenged the chicken.

The lawyers stopped eating and watched my client as he lost to the chicken about an hour before he was going to testify. After he lost to the chicken, everyone was remarkably quiet and nobody seemed to be eager to talk to me.

In a funny way, the loss to the chicken confirmed for me my client’s integrity and it fit quite nicely into my new strategy.

When I put him on the stand, I abandoned my prepared outline and changed gears. I kept it short, simple and direct. I flat out asked him whether he had stolen anything that became part of this purloined patent. He was surprised that I had changed our planned testimony. He replied instinctively without reservation and answered no.

I then announced that was the only question I was going to ask and then I sat down. The plaintiff never cross-examined him because he was small potatoes, and there wasn’t much testimony to cross examine.

Thereafter, I also changed gears and cross-examined the plantiff’s patent expert witnesses about the trade secrets case, which they knew nothing about. They cared only about the patent, not about the claim of trade secrets theft.

I asked each expert witness the same question: “After the years that you have put into preparation for your testimony, did you find any evidence that convinced you of my client’s guilt?” In each case, they shook their heads and answered no.

The other lawyers thought I was crazy and looked down at their papers in an effort to avoid laughter.

I added insult to injury by dramatically turning to the court reporter and saying that I wanted a copy of the answer to my question and, in each case, the court reporter nodded and I would get a couple of pages of transcript the next day.

After almost two months of trial, we went to closing, and again all the defendants gave days of closing arguments. When it came to me, I put my watch on the lectern and I looked at the jury and said, “Remember my promise of almost two months ago? I am going to give you a closing that will not exceed 15 minutes.” Then I quoted from the transcript pages that I had requested from the court reporter, the answer from each expert witness that stated they had found no evidence relating to my client.

Back then, during breaks, everybody could smoke cigarettes in the hallway. I got to know the plaintiff because he smoked a pipe and I smoked cigarettes, so we shared matches and talked.

He saw what I was doing and actually appreciated it. He would always start off after we inhaled and then, with a smile, would laugh and say, “smoke and mirrors.”

All the other lawyers waited three days for the verdict. I had to catch the train back home because I had a small trial starting the next day. After three days, the jury came down hard against all of them, but acquitted my client.

A day later I got a faxed letter from the plaintiff. He had won big, but he still sent me a letter with a smiley face and “smoke and mirrors — congratulations.”

So much of the time, appearances are more powerful and persuasive than the facts. We will see if Trump “fools the people” in the end.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 10, 2023 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Travel

You think you’ve been embarrassed? Well, I’ve got you beat.

First, it all happened to me on the other side of the planet so I couldn’t go home, turn off the lights and put my head under the pillow.

It happened in Xi’an, China, in an airport the morning I was scheduled to fly to Chongqing to see a panda sanctuary, then board a boat to go down the Yangtze river through the Three Gorges, and then down to Shanghai.

Second, I was traveling with a small group and the Xi’an Airport was huge, so I had nowhere to hide as my embarrassment went on and on and on…

It all started innocently at dinner the night before we were scheduled to fly out of the Xi’an airport the next morning. Our guide addressed the group and informed us that because our plane left so early the next day we all must have our bags packed and outside of our door at 4:30 so they could be picked up and taken to the airport before we went to breakfast.

Everything had to be packed except the clothes we would be wearing the next day and whatever toiletries we required for that morning.

We were told that those toiletries, once used, had to be carried on our person until we landed at Chongqing airport several hours later at which time we could return them to our suitcases.

After dinner that night, we all went up to our rooms, picked out the essential toiletries, which in my case was toothpaste, toothbrush, shampoo, razor, soap, and hairbrush. I also chose my clothes for the next day, which in my case, were one of my endless pairs of khaki pants, a blue long sleeve business shirt, underwear, sox and shoes.

All the rest was packed in the suitcase, which I put outside the door right before I set the alarm and went to bed.

The next morning when my alarm went off, before I showered and shaved, I peeked out the door. My suitcase was gone and on its way to the airport. I looked at the clock and measured the short time I had to get to breakfast.

After my shower, I bundled up my toiletries, put on my blue business shirt and started to pull up my khaki pants, but couldn’t understand why I couldn’t get them on until I realized that the only pair of pants I had to wear were actually those I had mistakenly packed, which unfortunately belonged to my teenage son.

My son has a 32-inch waist. I do not.

I was running out of time. I had to get to breakfast.

I grabbed both sides of the pants so that my fingers gripped the pockets and I hoisted as hard as I could. No progress.

Next, I lay on my back on the bed with my feet extended in the air and bounced on the bed to get maximum leverage, kicked my feet into the air and yanked with all my strength. No progress.

The top of the pants made it to maybe slightly above my crotch. I’m pretty certain I did not get the pants high enough to halfway cover my back end. Nothing.

Next, I tried straddling a chair and forcefully rode my pants like a cowboy rides a horse in order to force the crotch into submission. I then tried jumping up and down to get maximum thrust, lift and torque. Nothing. This was not good!

I had to get to breakfast but I couldn’t leave the room. This was not good at all!

I reassessed my situation.

I still had to put on my shoes and socks. I would have to roll up the bottom of the pants so that I wouldn’t trip over them.

I was able to walk, but only if I could hold the top of my pants up as high as possible, and walk with my knees banging together every time I took a step.

I searched the room for any possible help. I was fortunate to find yesterday’s Chinese newspaper — bright with color — to cover my crotch.

It was a very long and slow elevator ride for every inch of the decent down maybe three floors. I noticed that the Chinese people in Xi’an, at least in this elevator on this particular morning, tended to be very quiet as they tried to find someplace else to look other than at my crotch.

My group at breakfast was less forgiving. They had to stop eating because they couldn’t stop laughing.

Our guide tried to be helpful and encouraged me to wander the airport to find a clothing store, apparently in the hope that I could learn Mandarin instantly and acquire a pair of pants that was twice the size that any self-respecting member of the culture would never wear.

The guide was just trying to be helpful I know, but didn’t seem to understand that I was really, at this point, no longer interested in clothing. I was no longer hoping to fit into the culture.

I was hoping to vanish from the face of the earth.

Everyone in the airport seemed to be walking by and rubbernecking in order to catch sight of whatever everyone else was laughing at.

I was completely hunched over, gripping my newspaper and pants, with my pant legs rolled up above my ankles and, just to add to my unlikely assimilation into the culture, I was wearing my disposable razor, shaving cream, toothbrush, toothpaste and hairbrush bundled up into a boutonniere blooming from my shirt pocket to add to my look.

The Chinese newspaper was fast becoming my most valuable asset since, as it turned out, my seat on the plane was between two meticulously dressed, very frightened Chinese businessmen who apparently feared any eye contact with me, their fellow traveler, for fear that it might prompt me to flash them.

In times like this I try to focus on making my situation into a positive learning experience.

After thinking about my situation for a little while, I concluded there wasn’t a lot to learn so, in the alternative, I thought it might be helpful to try to imagine what could be worse than what was happening to me at this exact moment.

I no longer wonder what it must feel like to wear a miniskirt if you are knock kneed, but that wasn’t bad enough, so I tried to imagine what it was like to wear a miniskirt, knock kneed with high heels.

I made sure that I would be the last person to leave the plane when we landed. in order to give the baggage handlers extra time so when I went to pick up my bag it would be there.

I hid in the airport men’s room for a while. I was afraid I had permanently injured my lower intestines. I was sure I had bruising. I couldn’t really lift or lower my pants now.

Eventually, I built up all my courage and raced through the teeming airport hunched over, with one hand holding the top of my pants and the other gripping my newspaper.

I swooped down on my bag and hauled it into the men’s room, found a stall, opened the suitcase, liberated myself of my son’s pants, and instantly threw them away for no good reason other than I needed to purge them.

A few months ago, I went on a trip with some of that same group that had gone on the China trip. When my story came up, I refused to relive the experience, so they went right ahead and told it anyway. They kept on embellishing the story at my expense.

The trip to China was 10 years ago, and the listeners could not stop laughing. Apparently, it gets better and better.

One person, who I am not sure was even on the China trip, claimed to have seen it all from the back and referred to it as “the morning the moon rose over the Yangtze!”

I must now live in infamy forever.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 3, 2023 | Featured, Personal

Recently, as I waited to exit a Southwest flight in Baltimore, a fellow traveler — who also turned out to be a fellow retired lawyer — laughed and asked me whether retirement had changed my life much, or perhaps had even changed my view of humanity.

The two of us had met and decided to sit together in the Boston airport while waiting to board from positions A-1 and A-2 for business class seating.

Now we both were waiting patiently to exit from the middle of the plane because the 22 wheelchair-assistance passengers who had pre-boarded would be exiting from their aisle seats, which they had taken when they entered the plane.

I decided to answer the two questions separately. First, I told a brief story to illustrate what my life was like as a practicing lawyer:

One afternoon around 4:00 o’clock while I was actively practicing law years ago, I developed chest pains. I was on the phone with a witness for an upcoming trial, so I decided that I would finish the call before I dealth with the pain in my chest.

After the call, I decided to try hanging off a door to ease the pain.

I found a door that was part open, put my hands on the top, and hung from the door to see if the pain would go away. Ater a while it did so I went back to work.

Later that night at dinner with my wife and children, the pain returned. I didn’t want to trouble anybody, so I left the dinner table, found a door and hung off of it for a bit until the pain subsided again. Then I flushed the toilet for cover and went back to dinner.

But later, around 1:00 o’clock in the morning, the pain returned. I got out of bed to find an open door somewhere in the house. My wife woke up, rolled over, and saw me hanging from the bedroom door. She told me to go immediately to the hospital.

However, when I went into the closet to get dressed, the only clean shirt that was readily available was a white shirt just back from the dry cleaner. I put it on and looked for a pair of pants. I found only a suit, which I immediately put on and then I was stuck with a problem. I couldn’t possibly go in a white shirt without a tie, so I just reached into the rack of ties and put on the first one I grabbed. I didn’t turn on the light because I didn’t want to wake up the house, so I didn’t even know what color it was.

Finally, I got lucky. I had no problem tying the tie in the dark.

It was about 2:00 o’clock in the morning and the roads were empty as I sped down the highway toward the nearest hospital. The pain was getting pretty bad and for the first time it occurred to me I might die.

In that moment in the dark, my mortality became very real to me. I concluded I might never leave the hospital.

It was a remarkable revelation for me, so I reached into the glove compartment and pulled out what I considered would probably be my last cigarette.

At the emergency room parking lot, I started to get out of the car, but realized that my briefcase was in the passenger seat next to me. I was concerned that there were confidential papers belonging to my client pertaining to the trial that were in that briefcase so I brought the briefcase with me into the emergency room and politely let the nurse know that I was having chest pains.

Before I knew what was happening, I was being pushed back into the seat of a wheelchair with my briefcase squarely riding on my lap and then wheeled at a high rate of speed toward cardiac care by a nurse in the night time hospital. She patted me on the shoulder and asked in an exasperated voice “So you think you might have a heart attack at 2:30 am and be back at the desk by 7:00?”

Well, the nurse overreacted. It wasn’t a heart attack. It was just gallstones that nearly killed me, but I had been right, hadn’t I?

As my story ended, we began to move down the aisle and exited the plane. Gathered by the gate were almost 20 wheelchairs. None of them had been used to take any of the passengers into the airport.

My traveling companion and I both laughed good-naturedly. “So, what about my second question,” he prompted. “Has your view of humanity changed?”

“It’s all how you look at things,” I replied with a wry smile. “Isn’t it wonderful that Southwest doesn’t charge extra for miracles?”

We laughed, then hurried to our next transportation.