by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 21, 2023 | Featured, Law, Personal, Politics

Abraham Lincoln famously said, “You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time.”

Lincoln’s quote applies to the voting public as well as trials before a judge or jury.

Former President Trump appears to be trying to win his legal cases with political arguments. He cares little about judges, but is determined to win an election, in order to pardon himself or have another Republican pardon him if he doesn’t run. Trump is leading in the polls, so this should be easy for him to do.

I learned how to do this from a chicken.

Years ago, I represented one defendant of four that were accused of stealing trade secrets that were provided to the lead defendant who allegedly included them in a patent for software designed for huge construction projects.

The plaintiff was a self-taught computer programmer. He was represented by a prominent New York patent firm.

The lead defendant was represented by a large Chicago law firm, which had contracted for the entire floor of an NYC hotel for the two month trial. The four trade secret defendants were represented by separate individual lawyers. I was one of them. The case was tried before a jury in the federal court in Manhattan.

I liked my client. I believed in his innocence after watching how he lived. Over the two years of depositions and trial prep, I became convinced of his innocence.

He had gotten a scholarship to college as an athlete. He struck me as a fellow who played hard, but he played by the rules. He was remarkably oblivious to how personal impressions shape jury decisions, perhaps because he was so straightforward.

The large Chicago firm gave the opening statement for the defendants that ran for a day and a half. They kept open every possible defense available and there wasn’t a defense that they didn’t like. One juror went to sleep but the lawyers seemed too busy to notice.

The other four defendants, the trade secrets defendants, each argued in their openings for at least two to three hours each, except for me.

As I watched those opening statements, I abruptly changed my strategy given the jury’s reaction to the openings.

I told the jury my opening statement would be no more than 15 minutes and whenever this trial ended, my closing summary would be no longer than 15 minutes and they would find that my client was not guilty.

I told them a little about my client and his little company, and then I sat down easily within the 15 minutes I had slotted for myself.

Every day of the trial, all the lawyers for the defendants went to lunch in Chinatown, which was right behind the Federal Court in Manhattan. The restaurant we went to had two attractions: 1) the dancing chicken, and 2) the chicken that would play tic-tac-toe against you.

You put the coins into the slot, and out would come the chicken. It would stare at you until you made your first move, tapping on the tic-tac-toe board that was on the glass that separated you from the chicken. An “X” would appear. The chicken would then make its counter move, pecking its choice of position, where an “O” would appear.

Even though all of the defense lawyers went to eat at this Chinese restaurant, none of them played this game because, I’m convinced, they didn’t want to dim their genius by losing to a chicken. That is certainly why I didn’t play against the chicken.

This was a serious chicken. The chicken was really good. It was so good that years later when the chicken died it got an obit in the New York Times. It was all a con job, but everyone was captivated by it. The chicken was given a signal where to pack in order to get fed, and thus peck the correct box.

As the trial progressed, I grew more worried that this case was so complicated that nobody understood it. Worse, now there were at least three jurors who were dozing off.

I became convinced that the defendants would not be considered individually. I feared that they would be lumped together with the patent defendent, and the smaller trade secret defendants would be found guilty as well, including my client.

When it became my client’s turn to testify, he came to town and, before he took the stand, we went to the Chinese restaurant. However, on the way to the men’s room, when I wasn’t looking, my client challenged the chicken.

The lawyers stopped eating and watched my client as he lost to the chicken about an hour before he was going to testify. After he lost to the chicken, everyone was remarkably quiet and nobody seemed to be eager to talk to me.

In a funny way, the loss to the chicken confirmed for me my client’s integrity and it fit quite nicely into my new strategy.

When I put him on the stand, I abandoned my prepared outline and changed gears. I kept it short, simple and direct. I flat out asked him whether he had stolen anything that became part of this purloined patent. He was surprised that I had changed our planned testimony. He replied instinctively without reservation and answered no.

I then announced that was the only question I was going to ask and then I sat down. The plaintiff never cross-examined him because he was small potatoes, and there wasn’t much testimony to cross examine.

Thereafter, I also changed gears and cross-examined the plantiff’s patent expert witnesses about the trade secrets case, which they knew nothing about. They cared only about the patent, not about the claim of trade secrets theft.

I asked each expert witness the same question: “After the years that you have put into preparation for your testimony, did you find any evidence that convinced you of my client’s guilt?” In each case, they shook their heads and answered no.

The other lawyers thought I was crazy and looked down at their papers in an effort to avoid laughter.

I added insult to injury by dramatically turning to the court reporter and saying that I wanted a copy of the answer to my question and, in each case, the court reporter nodded and I would get a couple of pages of transcript the next day.

After almost two months of trial, we went to closing, and again all the defendants gave days of closing arguments. When it came to me, I put my watch on the lectern and I looked at the jury and said, “Remember my promise of almost two months ago? I am going to give you a closing that will not exceed 15 minutes.” Then I quoted from the transcript pages that I had requested from the court reporter, the answer from each expert witness that stated they had found no evidence relating to my client.

Back then, during breaks, everybody could smoke cigarettes in the hallway. I got to know the plaintiff because he smoked a pipe and I smoked cigarettes, so we shared matches and talked.

He saw what I was doing and actually appreciated it. He would always start off after we inhaled and then, with a smile, would laugh and say, “smoke and mirrors.”

All the other lawyers waited three days for the verdict. I had to catch the train back home because I had a small trial starting the next day. After three days, the jury came down hard against all of them, but acquitted my client.

A day later I got a faxed letter from the plaintiff. He had won big, but he still sent me a letter with a smiley face and “smoke and mirrors — congratulations.”

So much of the time, appearances are more powerful and persuasive than the facts. We will see if Trump “fools the people” in the end.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 10, 2023 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Travel

You think you’ve been embarrassed? Well, I’ve got you beat.

First, it all happened to me on the other side of the planet so I couldn’t go home, turn off the lights and put my head under the pillow.

It happened in Xi’an, China, in an airport the morning I was scheduled to fly to Chongqing to see a panda sanctuary, then board a boat to go down the Yangtze river through the Three Gorges, and then down to Shanghai.

Second, I was traveling with a small group and the Xi’an Airport was huge, so I had nowhere to hide as my embarrassment went on and on and on…

It all started innocently at dinner the night before we were scheduled to fly out of the Xi’an airport the next morning. Our guide addressed the group and informed us that because our plane left so early the next day we all must have our bags packed and outside of our door at 4:30 so they could be picked up and taken to the airport before we went to breakfast.

Everything had to be packed except the clothes we would be wearing the next day and whatever toiletries we required for that morning.

We were told that those toiletries, once used, had to be carried on our person until we landed at Chongqing airport several hours later at which time we could return them to our suitcases.

After dinner that night, we all went up to our rooms, picked out the essential toiletries, which in my case was toothpaste, toothbrush, shampoo, razor, soap, and hairbrush. I also chose my clothes for the next day, which in my case, were one of my endless pairs of khaki pants, a blue long sleeve business shirt, underwear, sox and shoes.

All the rest was packed in the suitcase, which I put outside the door right before I set the alarm and went to bed.

The next morning when my alarm went off, before I showered and shaved, I peeked out the door. My suitcase was gone and on its way to the airport. I looked at the clock and measured the short time I had to get to breakfast.

After my shower, I bundled up my toiletries, put on my blue business shirt and started to pull up my khaki pants, but couldn’t understand why I couldn’t get them on until I realized that the only pair of pants I had to wear were actually those I had mistakenly packed, which unfortunately belonged to my teenage son.

My son has a 32-inch waist. I do not.

I was running out of time. I had to get to breakfast.

I grabbed both sides of the pants so that my fingers gripped the pockets and I hoisted as hard as I could. No progress.

Next, I lay on my back on the bed with my feet extended in the air and bounced on the bed to get maximum leverage, kicked my feet into the air and yanked with all my strength. No progress.

The top of the pants made it to maybe slightly above my crotch. I’m pretty certain I did not get the pants high enough to halfway cover my back end. Nothing.

Next, I tried straddling a chair and forcefully rode my pants like a cowboy rides a horse in order to force the crotch into submission. I then tried jumping up and down to get maximum thrust, lift and torque. Nothing. This was not good!

I had to get to breakfast but I couldn’t leave the room. This was not good at all!

I reassessed my situation.

I still had to put on my shoes and socks. I would have to roll up the bottom of the pants so that I wouldn’t trip over them.

I was able to walk, but only if I could hold the top of my pants up as high as possible, and walk with my knees banging together every time I took a step.

I searched the room for any possible help. I was fortunate to find yesterday’s Chinese newspaper — bright with color — to cover my crotch.

It was a very long and slow elevator ride for every inch of the decent down maybe three floors. I noticed that the Chinese people in Xi’an, at least in this elevator on this particular morning, tended to be very quiet as they tried to find someplace else to look other than at my crotch.

My group at breakfast was less forgiving. They had to stop eating because they couldn’t stop laughing.

Our guide tried to be helpful and encouraged me to wander the airport to find a clothing store, apparently in the hope that I could learn Mandarin instantly and acquire a pair of pants that was twice the size that any self-respecting member of the culture would never wear.

The guide was just trying to be helpful I know, but didn’t seem to understand that I was really, at this point, no longer interested in clothing. I was no longer hoping to fit into the culture.

I was hoping to vanish from the face of the earth.

Everyone in the airport seemed to be walking by and rubbernecking in order to catch sight of whatever everyone else was laughing at.

I was completely hunched over, gripping my newspaper and pants, with my pant legs rolled up above my ankles and, just to add to my unlikely assimilation into the culture, I was wearing my disposable razor, shaving cream, toothbrush, toothpaste and hairbrush bundled up into a boutonniere blooming from my shirt pocket to add to my look.

The Chinese newspaper was fast becoming my most valuable asset since, as it turned out, my seat on the plane was between two meticulously dressed, very frightened Chinese businessmen who apparently feared any eye contact with me, their fellow traveler, for fear that it might prompt me to flash them.

In times like this I try to focus on making my situation into a positive learning experience.

After thinking about my situation for a little while, I concluded there wasn’t a lot to learn so, in the alternative, I thought it might be helpful to try to imagine what could be worse than what was happening to me at this exact moment.

I no longer wonder what it must feel like to wear a miniskirt if you are knock kneed, but that wasn’t bad enough, so I tried to imagine what it was like to wear a miniskirt, knock kneed with high heels.

I made sure that I would be the last person to leave the plane when we landed. in order to give the baggage handlers extra time so when I went to pick up my bag it would be there.

I hid in the airport men’s room for a while. I was afraid I had permanently injured my lower intestines. I was sure I had bruising. I couldn’t really lift or lower my pants now.

Eventually, I built up all my courage and raced through the teeming airport hunched over, with one hand holding the top of my pants and the other gripping my newspaper.

I swooped down on my bag and hauled it into the men’s room, found a stall, opened the suitcase, liberated myself of my son’s pants, and instantly threw them away for no good reason other than I needed to purge them.

A few months ago, I went on a trip with some of that same group that had gone on the China trip. When my story came up, I refused to relive the experience, so they went right ahead and told it anyway. They kept on embellishing the story at my expense.

The trip to China was 10 years ago, and the listeners could not stop laughing. Apparently, it gets better and better.

One person, who I am not sure was even on the China trip, claimed to have seen it all from the back and referred to it as “the morning the moon rose over the Yangtze!”

I must now live in infamy forever.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 3, 2023 | Featured, Personal

Recently, as I waited to exit a Southwest flight in Baltimore, a fellow traveler — who also turned out to be a fellow retired lawyer — laughed and asked me whether retirement had changed my life much, or perhaps had even changed my view of humanity.

The two of us had met and decided to sit together in the Boston airport while waiting to board from positions A-1 and A-2 for business class seating.

Now we both were waiting patiently to exit from the middle of the plane because the 22 wheelchair-assistance passengers who had pre-boarded would be exiting from their aisle seats, which they had taken when they entered the plane.

I decided to answer the two questions separately. First, I told a brief story to illustrate what my life was like as a practicing lawyer:

One afternoon around 4:00 o’clock while I was actively practicing law years ago, I developed chest pains. I was on the phone with a witness for an upcoming trial, so I decided that I would finish the call before I dealth with the pain in my chest.

After the call, I decided to try hanging off a door to ease the pain.

I found a door that was part open, put my hands on the top, and hung from the door to see if the pain would go away. Ater a while it did so I went back to work.

Later that night at dinner with my wife and children, the pain returned. I didn’t want to trouble anybody, so I left the dinner table, found a door and hung off of it for a bit until the pain subsided again. Then I flushed the toilet for cover and went back to dinner.

But later, around 1:00 o’clock in the morning, the pain returned. I got out of bed to find an open door somewhere in the house. My wife woke up, rolled over, and saw me hanging from the bedroom door. She told me to go immediately to the hospital.

However, when I went into the closet to get dressed, the only clean shirt that was readily available was a white shirt just back from the dry cleaner. I put it on and looked for a pair of pants. I found only a suit, which I immediately put on and then I was stuck with a problem. I couldn’t possibly go in a white shirt without a tie, so I just reached into the rack of ties and put on the first one I grabbed. I didn’t turn on the light because I didn’t want to wake up the house, so I didn’t even know what color it was.

Finally, I got lucky. I had no problem tying the tie in the dark.

It was about 2:00 o’clock in the morning and the roads were empty as I sped down the highway toward the nearest hospital. The pain was getting pretty bad and for the first time it occurred to me I might die.

In that moment in the dark, my mortality became very real to me. I concluded I might never leave the hospital.

It was a remarkable revelation for me, so I reached into the glove compartment and pulled out what I considered would probably be my last cigarette.

At the emergency room parking lot, I started to get out of the car, but realized that my briefcase was in the passenger seat next to me. I was concerned that there were confidential papers belonging to my client pertaining to the trial that were in that briefcase so I brought the briefcase with me into the emergency room and politely let the nurse know that I was having chest pains.

Before I knew what was happening, I was being pushed back into the seat of a wheelchair with my briefcase squarely riding on my lap and then wheeled at a high rate of speed toward cardiac care by a nurse in the night time hospital. She patted me on the shoulder and asked in an exasperated voice “So you think you might have a heart attack at 2:30 am and be back at the desk by 7:00?”

Well, the nurse overreacted. It wasn’t a heart attack. It was just gallstones that nearly killed me, but I had been right, hadn’t I?

As my story ended, we began to move down the aisle and exited the plane. Gathered by the gate were almost 20 wheelchairs. None of them had been used to take any of the passengers into the airport.

My traveling companion and I both laughed good-naturedly. “So, what about my second question,” he prompted. “Has your view of humanity changed?”

“It’s all how you look at things,” I replied with a wry smile. “Isn’t it wonderful that Southwest doesn’t charge extra for miracles?”

We laughed, then hurried to our next transportation.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 22, 2023 | Featured, People, Personal

Many of us in our joyous misspent youth, particularly in our teenage years, enjoyed the undisciplined fun of our juvenile hubris.

Hubris is an ancient Greek word that describes excessive exuberance, confidence, or pride, which can often bring about one’s downfall.

The art of teaching teenagers during the hubris years requires a middle path, somewhere between crushing the hubris and leaving it untethered. This middle path requires the difficult task of helping a student to channel hubris to promote individuality and personal growth, because this youthful burst of enthusiasm often can be the first sign of what a young person’s real interests really are.

Think of the people you know who discover that they hate their careers in midlife and go in an entirely different direction or, worse, don’t.

My experience is that many of these people were not educated to question and challenge their conclusions. Rather, they were educated to take good notes and vomit it all back on the final exam to be rewarded with a great grade, and then passively step into careers in which they were never really interested.

Whitney Haley, our drama teacher at the Cambridge School of Weston, was a master of the middle path. He marshaled his resources and directed us with surgical, gentle humor.

Whitney was an aging, portly diabetic, who had long ago retired from a career in the silent movies. He did everything with an intentional dramatic flair. He pronounced his name with one hand dancing in the air as Whit-Née (brief dramatic pause) Hay-Lée (and then wait for our response). He herded us with humor rather than a cattle prod. Everybody loved Whitney Haley!

In our high school play, I was cast in the role of John Hale, the strict Puritan minister, in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. Before opening night, we all applied our own make up, which was approved by Whitney before we went on stage.

I came to the conclusion, as I was putting on makeup for the first time ever, that John Hale was actually “tall, dark, and handsome.” I decided he had to be Movie Star Handsome.

Whitney walked by and noticed that I was becoming darker and darker. With his customary dramatic flare and his best stage whisper, he intoned: “Perhaps my memory has failed me. Isn’t this a play about a witch-hunt, which did not happen to take place on the beach.”

The dressing room broke into laughter but it was not at me, it was how Whitney delivered his edict. I had not been shamed. I had just been encouraged to take a second look in the mirror, and become educated as to my “hubris.”

Unquestionably, Whitney Haley‘s favorite student was Greg Fleeman, who could not stop himself from making people laugh. He literally could not help himself. He was constantly funny.

When Greg would bring his chaos to Whitney’s classroom and inadvertently shut down the class, Whitney, with his perfect timing, would stop the class, go into his pocket, and offer him a handful of change: “Greg-or-ee. Would you mind if I interrupted you briefly and trouble you to step out of the room, travel down the hall to the candy machine, and acquire a Milky Way candy bar for me, which I will gladly give you as a reward at the end of this class if you will allow me to continue to pursue my chosen profession?“

Whitney, with his perfect timing, would regain order to his classroom with humor and without injury or shame.

One Christmas vacation, Greg invited me back to visit his family in Miami. His father had been a developer of real estate on Miami Beach, which had made him very wealthy, but Greg, who I believe was his youngest son, had absolutely no interest in taking over his father’s business. Greg’s family had surrendered their son to the Cambridge School Of Weston to let him be who he was, despite their ambitions for him.

The first night I was invited to a somewhat formal evening meal. Mr. Fleeman sat at the head of the table. Greg never stopped talking, and his father never stopped laughing uncontrollably.

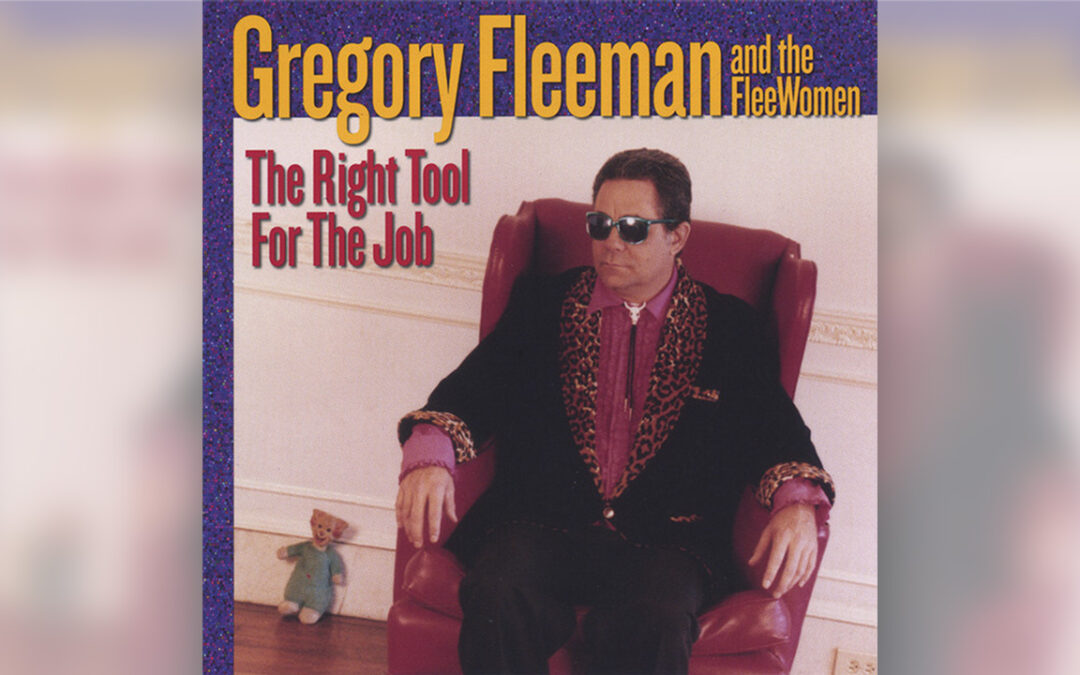

Greg went on to become a very original and eccentric rock musician. He also became the apple of his father‘s eye, the family business be damned. Greg was much too eccentric to be appreciated by the audience of his day, but he was invited regularly backstage by those more famous than he.

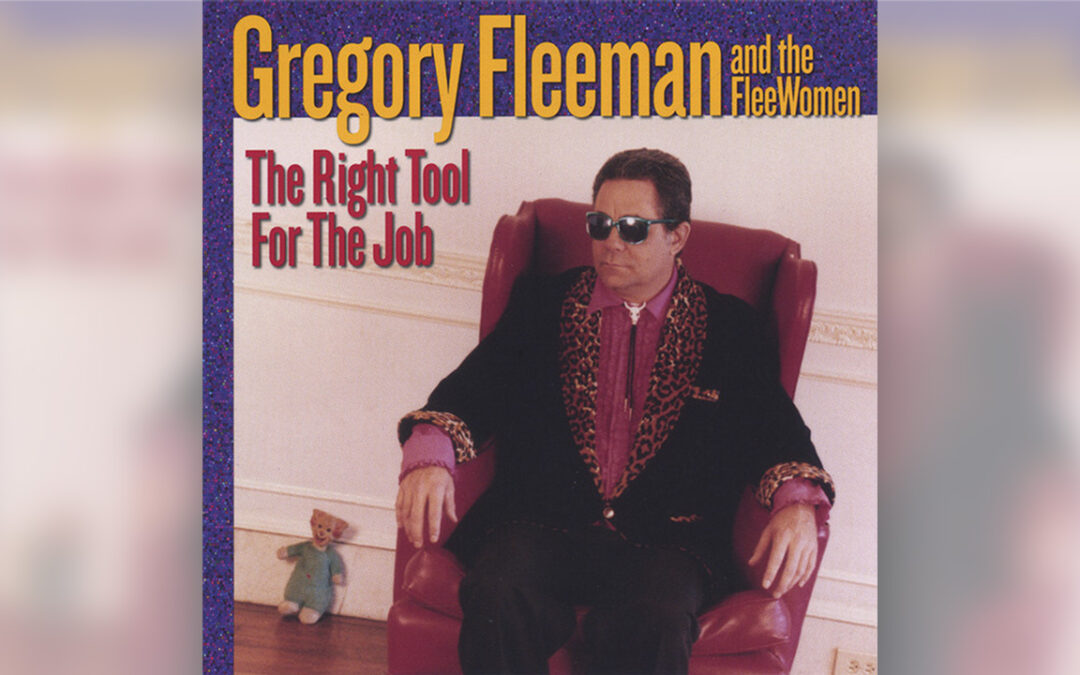

I saw him perform with his band, Greg Fleeman & the FleeWomen, at a small venue in Greenwich Village. He had a small but very loyal following. He was like a standup comedian with an amazing voice. He was always Mr. hubris. but with Whitney whispering in his ear.

Greg Fleeman was far too original to even be considered by schools that granted good grades to those who were able to take notes and recite back what the teachers had said rather than question everything, which is what CSW had taught us to do.

Many of the people who I went to school with describe their experience at the Cambridge School Of Weston as “life-saving.” So it was, not only for Greg Fleeman, but also Whitney Haley and me.

Whitney is long since gone and Greg Fleeman died last year, but he left a CD, “The Right Tool for the Job,” which I go back to again and again, just because it holds all of his irreverence, both in his lyrics and his orchestration. My favorite tracks are “My Ex Wife” and “Skin Tango.”

You can listen to it on YouTube: https://youtu.be/wjqnSOl41Ac.

He was original, and became himself because everybody else was taken.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 15, 2023 | Featured, People, Personal

Back when I was growing up, I was taught two different definitions of success: the so-called “self-made man,” and the person who creates community. For me, two very different people have proved this point.

One was a client of mine in the early years of the law firm I’d created as a sole practitioner in 1990. He was a businessman from rural, hardscrabble Pennsylvania, who had moved to Maryland when he was young and made a lot of money, developing lots for home construction in the Baltimore suburbs. With his success, he built a grand house, lavished gifts upon his wife and three boys and, for himself, he bought a limousine and hired a driver.

The businessman defined himself as a “self-made man.”

The other was my soccer coach at the Cambridge School of Weston, who built a high school sports team at a progressive school in the late 1960s. He was soft-spoken, had an easy smile and natural authority.

Both were entrepreneurial but their styles couldn’t have been more different.

Cambridge School of Weston was a little progressive school outside of Boston. For every other school, the preferred fall sport was football. CSW offered either soccer or rugby, I think because the equipment was cheaper and both of these sports served the character of the school better than football.

Another difference was our mascot. The schools we played against had lions and tigers, bulldogs and bears. We had a gryphon, and our school newspaper was called The Gryphon’s Eye. For half my first year, I didn’t know what a gryphon was. When I looked it up, I found out it was a ”fabulous beast with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion.”

All the other schools had fierce animals, and we had a myth as a mascot, which seemed fitting.

This little progressive school changed my life. It bucked the system and the traditional trends of the times. It taught a Socratic education. It encouraged us to question everything.

Anyway, our soccer coach was typical for this school because he taught us to challenge traditional authority and conventual behavior.

At this time, the strategy of high school soccer was to kick the ball as far as you possibly could down to the other end of the field and then try to score before the other team’s defense would kick the ball back up the field and then try to score using the exact same logic and conventions.

This strategy for the long kick game was dependent on speed and power. It required constant, repeated substitutions of the entire offensive, midfield, and defensive players whenever there was a whistle or break in the action, before the players became exhausted.

Finley was outside of the box from the start. He had to be. We only had about 15 players to fill 11 positions and, to make matters worse, we were ragtag free spirits who sang and played guitar during free periods and attended school in sandals.

Discipline, like running laps, took some reprogramming.

Finley built his future team by turning disadvantage into advantage. He told us that we would not substitute any of our 11 players unless there was an injury serious enough to cause removal. He knew our fear of exercise was real.

He informed us that we would have to get in shape, but he would not run us the way the other teams were trained. He had a plan. He informed us that anyone who kicked a ball that went over the height of the knee of the teammate we were passing to would have to instantly do a lap.

Findley built an offense out triangles. All we had to do is maintain control of the ball by passing, no higher than the knee of the recipient, and that person did the same thing to another teammate to complete the triangle. Once that was established, we were in control of the ball until we could take a shot on the opposing goaltender. If we could perfect this style, we could run the other team ragged, no matter how many substitutions they made.

Basically, it was pinball, but we bonded around it, pretty much mastered it, and my recollection is that we lost only one game against huge high schools, who replaced lines and kicked the ball down the field until we got the ball and again controlled it and scored.

We never were as big or athletic as the other teams. We were in shape, but we never ran like the other teams did. We didn’t have to. Because I was the laziest person on the team, I was the goalie. I think I only was scored on once the entire season not because I was any good but because I never saw the ball.

Findley was admired as a genius but not because he was a self-made man.

The client I represented who saw himself as a self-made man believed the soul of American capitalism was dog-eat-dog. He would, where possible, never pay his bills and, before I represented him, his prior lawyer had set up corporations within corporations that had no assets so that when a lawsuit was filed against him, there would be no money to pay the opponents if they won.

Eventually, no one would do business with him.

He lavished gifts on all of his children because it was important that they loved him, but he refused them a college education because he had none and he did not want them to be superior to him. Two of his three boys became dependent on drugs and were homeless for a period of time.

In contrast, Finley built a team that was a small but cohesive. He forced us to get out of ourselves and into supporting each other and our goal, which was to patiently beat better teams.

I’ve always believed that you are what you do, not what you say. Findley was way ahead of his time in the world of American soccer. The passing game that he taught us had been used before in Europe but he adopted it to fit his needs.

I learned from his wonderful madness.

My client’s wife called me moments after her husband died. He had been waiting for a heart transplant and was receiving daily transfusions to stay alive. When she called me, she was in tears. She said his last words were, “I can’t see! Why can’t I see? I’m not ready to die yet. I’m not ready to die.”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 2, 2023 | Featured, Humor, Law, Personal

I want to tell you about a special award I created and bestowed upon myself.

The Stuffed Shirt Award.

Usually, awards are to celebrate accomplishment — with plaques or statuettes and a large party where such honors are bestowed, like The Oscars and Tonys, or Lifetime Achievement Awards.

However, there are also awards that single out questionable distinction.

For example, the Darwin Awards are annually given for “improving the gene pool.” This is deceptive because it only honors an act so stupid it often ends with the demise of the honoree and is thus given posthumously.

One of the early Darwin Awards went to a gentleman who put a jet rocket engine in the trunk of a Dodge Dart, and died after hitting a vertical cliff wall about 400 feet above the highway.

Somewhere between these two extremes lives the Stuffed Shirt Award.

The Stuffed Shirt Award is typically reserved for professionals, specifically professionals who think too highly of themselves.

The award requires a public demonstration of perceived self-worth, which must be 1) noticed by at least one other person and 2) leads to a moment of genuine disbelief demonstrated by a visible shake of the head by the observer.

An example would be the senior partner at a large law firm I was up against in NYC who FedExed his dry cleaning home to Chicago because he didn’t like the way the dry cleaners in New York City did his shirts.

Hence, the name of the award but the award is not about shirts alone. Here’s how I qualified:

I was fortunate when I first started my law firm back in 1990 to be representing a very large electrical contractor who routinely did huge jobs, such as the electrical work on Coke ovens at Bethlehem Steel, and also the Ted Williams Tunnel, which was towed in 12 sections by tug boats up to Boston from Maryland.

The case covered the construction of a subway system in southern Maryland leading from to Washington DC. There were loads of defendants.

It was an arbitration. The judge and everyone involved had agreed it should be held at the empty yet-to-be-opened subway station where the work had been done. I loved the idea because the subway station “courtroom” was my Exhibit A.

The Maryland State government had many branches and each had different lawyers representing them who were “in-house counsel.” I, however, was an independent lawyer with a big client and I was my own firm and I was damn proud of it.

I had all the makings of a stuffed shirt. All I needed was an event that would lead to a “genuine moment of sincere disbelief and the shake of the head” to be a competitor.

My client and I were seated in the middle of several tables pushed end-to-end, with all the opposing lawyers spread out on the other side.

As the arbitration began, each lawyer introduced their agency. They started at one end of the table, announced the agency, and then announced they were “in-house counsel“ for the agency.

The introductions went from left to right and finally ended after perhaps 15 minutes. None of them were independent counsel. They had all introduced themselves as “in-house counsel.”

Then it was my turn, and I decided that I needed to distinguish myself as an intimidating big shot lawyer.

I paused. I straightened the evidence books and the trial notebooks on the table, leaned forward in my chair, and announced:

“I’m Bob Bowie. Outhouse Counsel.”

My effort at intimidation had fallen short. The laughter rose and renewed several times, echoing in the large empty building. Thereafter, throughout the case, my fellow lawyers would periodically slap me on the back and say how funny I was.

I won the case but had dodged a bullet. There was no plaque or statuette. There wasn’t a celebration. They didn’t even know I had qualified for a Stuffed Shirt Award. To my amazement, this was the start of several long friendships.

Whenever I see them, they are quick to remind me that I am still their favorite “outhouse counsel.”

Self-importance can be like a hot air balloon.

It’s beautiful to see the world from an exulted height but returning back to earth may be its unexpected gift.