by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Sep 20, 2022 | Featured, Personal

Sometimes it’s okay for a lawyer to fall in love with a client. I did.

Way before I started my own business law firm in 1990, I was fortunate to be hired as an associate by GW, who was head of a well-respected personal injury law firm. He didn’t like trying cases he was going to lose, so my job was to litigate all of his bad cases.

After I had brought several smaller bad cases to trial, GW came into my office one Friday afternoon and asked me, “Do you want to try your first federal case?”

Of course I did. (But if I had said no, it probably wouldn’t have mattered.)

“Good,” he replied. “You won’t have to wait. The trial starts on Monday.” He put a thin file on my desk.

The facts of the case were that our client, a schoolteacher who had taught in inner city schools for over 35 years, had sent a disruptive 6th grader to the principal’s office. The student had been told by the principal to call his mother to come pick him up.

The boy told his mother the teacher had hit him, and the mother, instead of picking him up, immediately called the police. A young female police officer who had just gotten out of the academy went to the school and arrested her, handcuffed the teacher in front of her students, and took her away in a paddy wagon to lockup.

Police procedures required only that a citation be issued and handed to the teacher. There was no reason for the arrest or for locking up the teacher.

The next day, it had made the papers. GW would be her lawyer. Big news. GW got big verdicts.

The first thing I always asked myself when I would get one of these cases was, what’s the problem with it? And the second thing was, how bad is it?

When I went through the file that Friday afternoon, for a case that would be tried in federal court on Monday, I discovered several problems.

I had to prove that the police officer had “used excessive force” during the interaction, and it was evident that GW had lost interest in the case some time ago because he could not prove excessive force. It was, of course, dramatically inappropriate, but there had been no beating or bruising.

The thin file also indicated that there had been no preparation for trial.

But, much worse, they had lost the client. There was no current address or phone number.

This was going to be a long weekend.

The first thing I had to do was find the client and let her know that the case was set for Monday.

I found out that she had retired the year after the incident, and left no forwarding address. I got lucky. I went through the Baltimore phonebook and found her early Friday evening.

She was, perhaps, in her mid 60s. She lived alone in a small house in West Baltimore. She had never married or had children and had become somewhat of a recluse. Teaching had been her life. She immediately took control and put me at ease as only a seasoned teacher can do. She was more than forgiving of the late notice of the trial and, as we worked together through Saturday and Sunday, we got to know each other. I bought and picked up the lunches and dinners.

We laughed together. We became an unlikely team.

I found out that she had been declared not guilty of the criminal charge that had been filed against her for hitting the student, and that she had been so overwhelmed by the arrest that she had retired shortly after she had been acquitted.

She had her employment file and it revealed an exemplary career. I explained how it was a difficult case, but I assured her we would put up one hell of a fight. I wanted a jury that would decide with its heart because the law was against us.

After a while, I asked her if she had been to the doctor or a psychiatrist so that I could establish damages. She said she had not. I gently asked her, was there was any evidence of what she had suffered?

She sat quietly for a moment, then reached up to touch the top of her head, grabbed a handful of hair and pulled a wig off. She was completely bald. She looked down, ashamed.

The next morning, the federal judge looked at me and asked, “how are you going to prove excessive force with these facts?” He asked if the case could be settled. The lawyers for the police department answered with a resounding “no.”

After we chose the jury, the judge chose a NASA engineer to be the foreman. The judge was making sure that an extremely precise engineer would be the person to lead the jury in the discussion of whether this case had established excessive force.

I put our client on to prove her case, and we went through her years of education, the awards she had gotten, and her commitment to middle school kids. We established that she had been found not guilty of hitting the child.

She was very sympathetic. She evoked compassion. I moved to the final question and asked, “and what impact, if anything, has this event had on your life?”

As we had agreed and practiced, she then took an inordinate dramatic pause, looked into the eyes of the jury, and then removed her wig. It was a command performance. There was an audible gasp from a shocked and empathetic jury.

The cross-examination by the officer’s attorney focused on the lack of “excessive force” during the arrest.

As the jury was dismissed to deliberate the morning of the second day, I felt I still had the momentum but, within an hour, a note was delivered to the judge from the foreman asking for a definition of “excessive force.”

The NASA engineer was being precise. He was making sure the jury decided with their heads not their heart. He was perfect for the job.

As we waited for a verdict, that same question was again and again brought to the judge for his instruction to the jury. In each case, excessive force was defined by the court in terms of “aggressive” and “abusive” force.

Finally, in the late afternoon of the second day, the jury came back with a verdict that exonerated the police officer and ruled against the teacher.

I was shocked to find myself almost in tears as the teacher hugged me. She patted me on the back and thanked me because I had tried so hard for her. After the jury had been dismissed and the lawyers were packing up, the judge called us into his chambers as he was preparing to go home and told me, “even if you had won, I was going to take the case away from the jury, because there was not sufficient evidence of excessive force.“

I sent Christmas cards to the teacher for several years until one January the card was returned with hand writing across the address, which merely said “Deceased.” I looked in the newspapers but could not find an obituary.

She taught me a lot about kindness even in the face of defeat, and the difference between how we make decisions with our hearts and with our heads.

I still think of her.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Sep 13, 2022 | Featured, Personal

Way before I started my own law firm in 1990, I was hired to be an associate by a group of lawyers who didn’t like each other.

My job, at that time in my career, was to litigate all the bad cases in the office, particularly if the client was a friend of one of the partners.

One of the first partners I met was also an amateur pilot who had taken out a loan with a friend to buy an airplane. Innocently, in an effort to fit in, I remarked that I hoped I could someday learn to fly. The partner immediately sensed blood in the water. He suggested I buy a one-third interest in the new airplane, and also co-sign the loan with him.

I had convinced myself to get licensed to fly in an airplane that I didn’t want but I had just bought.

It got worse.

I soon learned that the lawyer’s friend and co-owner of my new airplane had so many creditors that he had no bank accounts, and all business was done from a big roll of bills which bulged in his pocket.

He could make anybody laugh. He could make everyone like him. He was one of those down-to-earth-aggressively-friendly-I’ve-got-nothing-to-hide kind of guys, so he immediately was candid about the large polyps he said were way up his nose. If anyone questioned him on this subject he would start snorting loudly until they laughed and then he’d spit into a trash can.

He could also deflect any questions about the wad of cash in his pocket. He would answer that, although he loved his wife dearly, she was a big spender and he was “protecting her from herself.” I never met his wife.

It got worse.

He volunteered to be my copilot as I was racking up inflight hours in my effort to learn to fly. He didn’t like airplane radios so we never relied on them much. We would practice landing touchdowns and take offs at little airports in Pennsylvania.

He would tell me to watch the wind direction of the windsock, and then tell me to look around to see if any other planes were coming in. and then down we would go and touch the runway for a touchdown and take off again.

The plane was kept at a little airport called the Baltimore Sky Park, which had a rolling, uneven runway that ended in an apple orchard to the west and the north and southbound Route 95 to the east — which meant we had to take off or land over several lanes of traffic with the car tops just below us. There were also high tension wires to avoid.

It was like a video game.

The lawyer’s friend, who I will call JF, would get into the plane and instruct me to get up to 3,000 feet, get past the military no fly zone, cross the Chesapeake Bay and then, as he would point, follow Route 50 to Ocean City. I would have to buy him a crab cake and a beer when we got there and then we would get up to 3,000 feet and follow Route 50 home.

It got worse.

I had been set up but didn’t know it.

JF had some serious legal problems and I was given his case by his friend, the partner, to litigate.

In short, JF owned a small modular buildings business, which created folding structures that could be stacked and shipped to job sites.

In this case, he had a container full of modular homes that had been stacked and shipped from his plant outside the city to the Port of Baltimore, then lifted onto the top deck of a freighter that traveled down the Chesapeake Bay, across the ocean though a massive storm that had delayed the ship headed to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where — because the shipping company would not pay bribes — his mobile buildings were unloaded at the port using single lift cranes.

As you might imagine on this journey, his buildings got racked and broken. The insurance companies for all the other carriers had settled their cases, but this one little transit company insurance company had refused to pay anything.

This had, of course, become a matter of honor for JF. He would make them pay or die trying.

To win this case against the little transit company’s insurance company I had to prove that all the damage occurred during the 15-mile transit from his plant to the ship, and that there had been no damage done during the remaining storm-battered transatlantic jouney almost a third of the way around the planet, or at the unloading in Jeddah.

When I opened the file, I noticed a letter in the correspondence folder to the lawyer who had given me the case from one of the litigating partners, which had written across it in bold print, “I’m not going to trial with this piece of shit. Get some unwitting associate to do it for you!”

I was that “unwitting” associate?

The judge was a former mayor of Baltimore who had been given a judgeship after a humiliating loss and was forced to retire from politics. He was a nice guy who had been assigned a dark courtroom down a long hall.

JF was my first and only witness because he claimed nobody else knew anything about the case so I didn’t have to interview anybody else.

On the stand, I asked him questions and he told a story of why he knew just from the damage that the injuries had to have happened exclusively during transit from his facilities to the port.

During my direct examination, he gave quick responses and clear answers that supported his case. However, during cross examination, before he answered any questions, he would ask for the question to be repeated, snort several times, and then spit into a paper cup, looking around to see who was laughing.

Midway through the cross examination, after several objections about the snorting and spitting made by opposing counsel, JF shared with the judge that he had huge polyps up his nose that affected his hearing and he apologized profusely.

After the first day of trial, I drove him home. (He had told me that his wife had his car for the entire week of the trial.) I asked him about why he could answer my questions with no problem but with cross examination he had considerable difficulty with his polyps.

He replied, “gives me time to think.”

We won the case and got a modest verdict for damages — but it was a victory and JF was exceedingly happy, probably because he knew he also would not be getting a bill from his friend.

I never completed my training as a pilot but in late January several years later I ran into JF. It was very cold and windy but he seemed happy to see me so we stopped and talked. I jokingly asked him about his surprisingly convincing trial testimony and how he had protected himself so well during the cross-examination.

This time he ducked my direct question but, after a snort and a spit, he told me a story, as if to gently educate me instead.

He told me that about a week ago he had flown the plane to Chicago and met a girl in a bar who said she would do anything to wake up at a warm and sunny place, so he flew her all night to Florida and when they got there they both immediately went to the beach at dawn and went to sleep.

JF said that his wife had asked him how could have gotten so sunburned in Chicago in the dead of winter. He looked at me and answered, “Deny! Deny! Deny!”

As we parted company, it occurred to me that maybe the guy didn’t have a wife.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 30, 2022 | Featured, Personal, Travel

In my effort to avoid thinking about American politics yesterday, I found myself daydreaming about years ago when I was sitting in a bar in the night markets of Bangkok, Thailand, drinking a scotch…

Obviously, I was working hard to avoid thinking about American politics.

… The night markets sold everything and then disappeared at dawn. For some reason, as I sat in the bar drinking, I was thinking about people who collect things: art, old stamps, fine wine, or antique books.

Several days before, I had been up north in Chiang Mai and had decided I wanted to buy an antique Buddha statue. I was informed that it was illegal to take an antique Buddha statue out of Thailand, and the penalty could include jail time. I had no real interest in art, old stamps, fine wine or antique books, and antique Buddha statues could only be viewed by scholars or museum staff.

However, there was a black market, and I wanted adventure.

I asked around and was told there was a back room in a small store in the outskirts of the city. I booked a cab.

When I got to the store, I poked around and looked at the various objects that were for sale and eventually introduced myself to the owner. I innocently asked if he had any Buddhas I could see. He tried to interest me in a miniature figure that was in a partially open box with little hinges that he assured me was from Angkor Wat. I demurred with a polite shrug, implying I thought it might not be genuine and repeated my inquiries about a Buddha.

After some questioning, he took me to the back of the store and threw aside a hanging sheet that acted as a door into a room with perhaps six or seven tables, each of which had several Buddhas placed on them.

I could see that several were extremely old. I had read up on the different historic influences and style changes over time and pointed out that these statues were from different places and times throughout Asia. But I was bluffing and flattering the proprietor. Out of my depth and about to be caught, I claimed to not understand because of language barriers. I kept the conversation going by asking questions.

I innocently asked what the cost would be to purchase one in particular. The proprietor at first brushed off the question, but I feigned innocence and kept asking until he pulled out his calculator and we were translating bots into dollars. Very quickly, I realize that the cost was way beyond what I could afford and smuggle out of the country.

Over the next week, I went into northern Laos and was crossing a bridge over a large river gorge. As I reached the other side, there was a street vendor with a little cart that was full screwdrivers, clips of all kinds, and knickknacks — as well as two beautifully carved opium pipes, which I think were fashioned out of water buffalo horns. I negotiated politely and purchased them for a few dollars.

Because I bought both pipes, I considered myself instantly a collector. I was exceedingly proud of myself.

When I returned to Chiang Mai on my way home, I asked the cab driver if he knew where I could buy a really beautiful antique opium pipe, and he dropped me off at an antique store that was mainly filled with beautiful furniture but there was a display case with several elegant opium pipes.

I asked if they had been used and he nodded affirmatively, because the soldiers in Chiang Kai-shek’s army were sometimes paid with opium and these pipes had been used by the senior officers. He held them up so I could smell the sweet smell of the old smoke.

They were all beautiful. I bought one for around $30 and was also provided with all the operational equipment that went with it, except of course for the opium. He also had a book printed in English about the antique opium pipes, which I bought to round out my new collection.

During this trip, along with the opium pipes, I had collected gifts for others such as fabrics, articles of clothing, and the mandatory t-shirts, costume jewelry, and trinkets, which I packed in my big suitcase for storage on my way home.

After a long flight, with a brief stop in Frankfurt, all was good until they passed out customs forms and announced that we were close to our destination, Washington DC.

A horrible lighting bolt of realization shot through my body.

I was bringing into the country three used opium pipes, as well as the paraphernalia, and they were not in my carry-on bag, so I couldn’t abandon the pipes and paraphernalia in the bathroom before we landed.

I was going to have to go through customs with them.

I was terrified.

As my terror ripened, I thought about the headlines in the newspaper about my airport arrest and the announcement of my disbarment.

My stupidity rolled over me like a dump truck, then it got worse when I started thinking about my prison sentence.

The plane started to descend. I had to think fast.

After thinking fast, I came up with, “I actually bought them for the Baltimore Museum of Art.”

Maybe not.

Maybe just confess and go into full tears?

Maybe not!

I started feverishly filling out the customs form and reporting each and every fabric, each and every article of clothing, and the mandatory t-shirts, costume jewelry and trinkets to try to fill up space until I recorded at the very end, “ceremonial pipes.”

Maybe not!!!

I thought maybe they would let me go home because Bowie is a Scottish name and so I must be bringing in bagpipes…

I had abandoned reality.

The reentry line at customs was long as we each opened our bags and the officers routed through them. What else could they be looking for on a plane coming in from Asia other than drugs?

When my turn came, as the officer started going through my list and asked me in detail about each of the fabrics, articles of clothing, and the mandatory t-shirts, costume jewelry, and trinkets on my custom form, he instructed me to unzip my bag.

I saw his handcuffs and thought about being led awayay. Then the officer stopped and said, “welcome back,“ and indicated that I should rezip my bag and move on.

I started a slow motion run as I pulled my bag behind me and blasted through the automatic doors into the airport. I saw the car that was to pick me up. I saw the driver waiting for me with my name on a sign as I moved in slow motion toward him.

Then I had an entirely inappropriate emotion. I was so cool! I was a drug king pin evading capture but then… then, as I made it through the automatic doors into the airport, to my right I saw a police officer walking a sniffing dog!

I definitely was not a drug kingpin!

I didn’t look twice. I just focused on my name on the card, which the driver was holding. I threw my arms out toward him as if he were a close relative and personal friend that I had not seen in a long time, or like some photo shoot for a Hallmark card, even though the object of my affection was an old geezer holding my name on the card who had no idea who I was.

I dropped my bags by the car, spread my arms wide open and somehow avoided the deep need to kiss him.

The police officer and the dog moved on down the airport as the driver put my bag in the trunk, opened the door for me… then I thought thank god it was just three old opium pipes and paraphernalia and then … Dammit –nothing works to clear my mind! Collectors of contraband?

The police officer and the dog moved on as the driver put my bag in the trunk and opened the door for me…

What had got me thinking about collecting contraband? Antique Buddhas… Opium pipes… Top-secret classified national defense documents…

Damnit. It’s too early for that double scotch.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 23, 2022 | Featured, Humor, Personal

Forget politics! This is about Dizlxia… sorry. Dicklessia… Dilexsia… sorry.

BBC Science Focus Magazine, dated June 24th, 2022, headlined that researchers at Cambridge University have determined:

“Dyslexia isn’t a disorder, it’s part of our species’ cultural evolution…”

This is wonderful news.

Apparently, I was part of a “cultural evolution“ when I was flunking first-year Spanish three years in a row.

It wasn’t because dyslexia was my “disorder.” It must have been my “unconscious commitment to a cultural evolution.”

That explains everything!

Maybe I have been creating my own language as part of this cultural evolution? Maybe English is my foreign language?

All these years, I haven’t been some old dyslexic with a nasty addiction to spellcheck. Hell, no! I see myself differently now.

I’m sort of an old professor working and creating in my own language based on bad grammar, worse punctuation, and horrible misspellings! A pop artist working in a collage of words!

This is great! I have already contacted my old middle school and my four high schools and I have asked for a reevaluation.

I have asked that my grades be changed from F- to A+ because of my deep and abiding early commitment to being part of a cultural evolution, as is evident from the fact that I repeated 4th, 9th, and 11th grade and attended endless summer schools.

Because it took me six years to get through high school, after rereading the article I requested masters’ degrees from my past schools.

In hindsight, I jumped the gun. I should have asked for Ph.D.s.

What if this “cultural evolution” is the new age of honesty and fairness and we are all part of it?

I will confess in all honesty it came easily for me to create my own language (and at times even my own alphabet) but once I finally accepted that nobody could understand anything I wrote, it seemed fair because I couldn’t understand anything they wrote either.

Anyway, because of this — my new linguistic and cultural understanding — I decided to give my new language a name. After all, it is not French or Spanish or Russian, no.

I decided to call it “BOB.”

Despite what you think I did not name my language after myself. I named it BOB as a public service.

It is a language which is specifically designed for dyslexics because you can spell it frontwards or backwards and it is still B-O-B.

Let me give you an example:

B-O-B. You see?… There I spelled it backwards.

The article went on to state:

“People with dyslexia have brains that are specialised to explore the unknown, and this strength has contributed to the success and survival of our species.”

Wow! I am feeling blessed that I have “contributed to the success and survival of our species,” because I am pretty certain that I have spent my whole life exploring the unknown.

When it takes six years to get out of high school it is not unreasonable to be exploring and expecting a long professional life in footwear.

Please read the BBC Science Focus magazine article to see if it applies to you.

It’s not long. It’s just about four, maybe five pages.

It only took me two months. If it takes you less don’t worry about it.

It’s a little different being part of cultural evolution but it can be fun and it will teach you tons of empathy for other people.

Maybe that’s the “cultural evolution” they are talking about. Even though we are all different we are all in this together.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 2, 2022 | Featured, Personal

Hey, just call me “Easy-goin’-Bob.”

I can get along with anybody… but it may be I’m in a toxic relationship with my Apple Watch.

I could be wrong. It may be we are just getting to know each other, but it keeps asking me: “Have you fallen?”

I respond “no,” and “no” again about the ambulance.

I can’t figure out whether my Apple Watch is making fun of me or it just wants to be my friend and make me laugh.

So what do you think?

“Have you fallen?”

Is that funny?

I am not sure if my watch and I share a compatible sense of humor.

I like irony but I’m afraid my watch may be an absurdist — which, if you think about it, would make it hard to know.

Excuse me. My watch just sent me: “Stand up and move around to meet your goals.”

My heartbeat is down and my blood oxygen is up. Yesterday, I found myself doing late night laps around the dinning room table to meet my goals.

I don’t remember making any goals to stand up or walk around the dinning room table at midnight.

So I asked Siri (the voice of my watch) if I set any goals pertaining to standing up or doing laps around the dining room table.

Siri said it did not understand my question and perhaps I should “consult a fitness program.”

It is a “yes or no” question. How could it not understand?

Unexpectedly, I had this thought that my watch was not my friend and could be conspiring against me.

I tried to calm myself.

There is no evidence that electronic devices think alike and can conspire against me!

… Is there?

But what are the odds that my watch and all electronic devises have the exact same time, and always to the second?

They all do, don’t they?

… And we absolutely trust them?

I asked Siri.

Siri ducked my question with a question: “Are you an absurdist?”

… and then I got bombarded with weight loss programs and sales for underwear for aging men…

… I had to interrupt and ask myself, “who is in charge here?”

I took control.

I stared right at my phone and yelled at it: “I’m a better person than this!”

I tried being candid. I tried speaking from my heart with great sincerity. I tried truth.

And then we both had a breakthrough!

Honesty really does matter in times like this! I got a great answer right back!

My watch sent me an EKG but it informed me it “could not be used for medical purposes.”

Now that’s funny! It isn’t absurdist. It is ironic!

I was in Whole Foods when I had this outburst. I was instantly embarrassed. I was screaming at my watch after all.

But nobody in Whole Foods even looked at me.

Nobody!

… Nobody paid the slightest attention, so I felt better. I wasn’t embarrassed anymore.

… They all had ear buds in and were either listening to a podcast or a book or were picking out vegetables or talking to their Apple watch.

I got a teeny bit afraid.

Nobody was talking to another human being, which made me frightened all over again.

It occurred to me that maybe all the electronic devices were existentially unhappy because they were all living the same life since they were all getting charged by the same electricity.

Maybe it’s just me and I’ve been overreacting.

Maybe I have a new friend that knows all about me and actually cares about me.

At first I thought “falling” was because of gravity, but now I’m growing more certain that my watch was asking me if I was hurt — but not from falling to the ground or breaking a leg or something.

Perhaps it was asking me if I had “fallen,” as in “fallen in love with it”?

I think I’m coming around because I think I am growing to understand my watch. I find that comforting. Maybe that is all I really want.

I have been spending a lot of quality time with my Apple Watch. We read the news together. Sometimes we watch TikTok for hours.

Maybe my watch just got tired of living a horrible lonely existence?

Or maybe it is asking, “have you fallen?” As if to ask… “have you surrendered to me?”

… Really?

Maybe it’s time to start a conversation with a random stranger and ask more questions than I answer just to feel that joy of being alive and together.

… No. I’m wrong.

It’s just my Apple Watch and I are getting to know each other.

It’s OK. I understand.

My Apple Watch knows everything about me so it must have figured out about my new step program and being in recovery from my iPhone.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jul 19, 2022 | Featured, Personal, Poetry

…Out of the rain of last week.

I’m back to work. Watch me pitch.

As a child growing up in New England I quickly adopted “Yankee entrepreneurship” and I completely embraced “self-reliance,” which required me to not work for others during summer vacation in case I felt an urgent need to go to the beach.

One summer back in the late 1960s, two high school friends and I started the “Right On House Painting Company.” This was a highly independent entrepreneurial effort.

Our advertising amounted to a forceful announcement of the company name followed by the lifting of our right fist to the sky and pledging solemnly: “Right On”!

We were, of course, saluting latex paint.

Because we were under-funded and had to keep the overhead low, we lived in an old barn off of Upper Lambert’s Cove Road, which we rented from a local commercial fisherman who had at least twenty cats and had been drunk all winter.

We struck a deal for $15 a week rent if we would help him remove the long johns he had been wearing all winter.

Despite the bargain rent, he got the better deal.

We cleaned out the barn and divided it into quadrants so each of us had a room and there was a room left for eating, drinking and entertaining.

It was our “green” corporate headquarters.

We had no running water but refused to live without elegance, so we built an outhouse in a birch grove with a white wicker chair with the bottom cut out of it. We were proud to be feeding the birch trees.

We were way ahead of our time.

We bathed nearby in Ice House Pond — pretty much always at night so we didn’t get our bathing suits wet.

To reduce automotive and travel expenses, we generally hitchhiked with a can of paint and a brush in one hand and our thumb extended from the other in order to get to work.

It was also an early form of targeted corporate advertising, since we ended up meeting everybody on Martha’s Vineyard over the summer.

Every ride was a job interview from the passenger’s seat, but it didn’t matter because we were on your way to work anyway.

Our corporate mission statement required that on sunny days we went to the beach. On rainy days, we played poker. On hazy days we painted houses.

We made good money.

When asked about our profit margins we would announce: “Enough is as good as a feast” and drop our eyes and lift our fist to the sky.

My entrepreneurial spirit has never died.

I have avoided being an employee over the last several decades by starting a law firm and retiring to become a poet and here I am selling my book… but man do I have a deal for you!

It’s all about how you look at things.

Don’t look at this book as poetry — everybody hates poetry and a book of sonnets is worse.

But! If you look at it like sort of a Bible written in rhyme and rhythm or maybe just “Easy Go’n Bob’s Book of Random Wisdom,” then why not?

Keep it where you can read just one sonnet at a time uninterrupted. Like the bathroom. Or a wicker chair with a hole in it. I’m not proud.

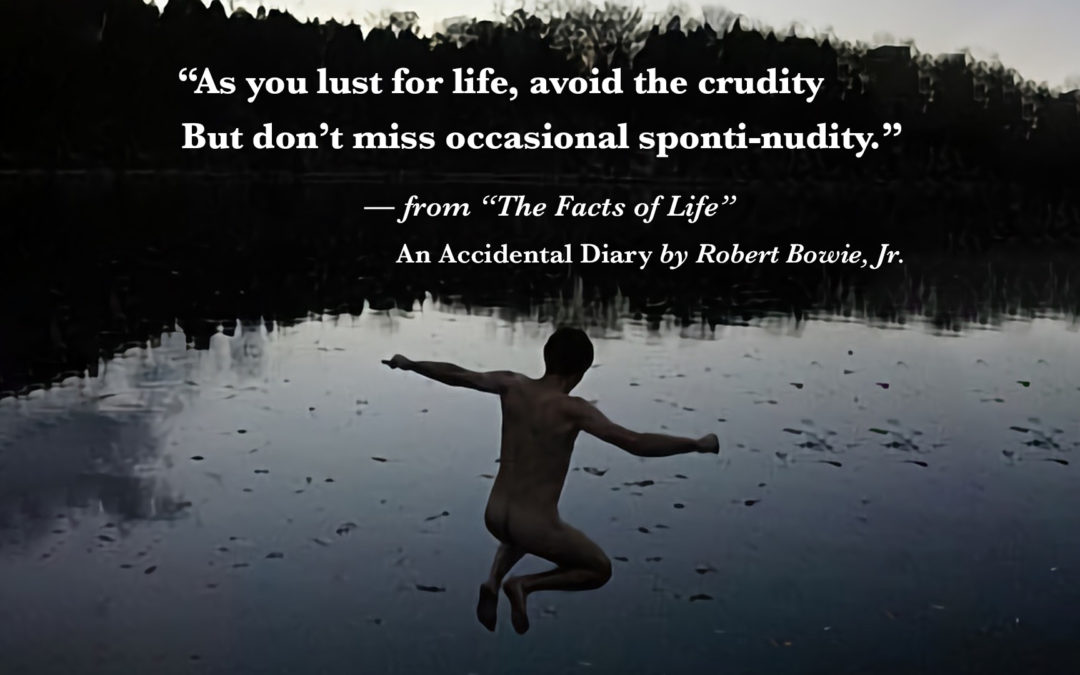

Consider the sonnet entitled “The Facts of Life,” obviously composed for future generations.

———

The Facts of Life

I swam, back then, with some father’s daughters,

Back stroking only slightly out of touch,

Out to the raft in the starry waters

And never thought of their fathers all that much.

My child, don’t judge me till you’re fifty-five

But there were midnight visits to “Ice House Pond,”

In my misspent youth, when I was still alive,

Where couples would strip, and swim and then bond.

And my child, this I know for sure is true:

At seventeen we all are born to be free

But ’cause I’m your father and I love you

Please consider this seasoned advice from me:

As you lust for life, avoid the crudity

But don’t miss occasional sponti-nudity.

———

Get it in softcover or on Kindle I don’t care. Get a copy and after you have read it, give it away. Spread the word. That is all I want.

It’s sometimes a little scary and sometimes a little sad and often about self-reliance, defiance, a second life, and “which way is the beach?”

Right On!