by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 30, 2020 | Poetry, Travel

Almost 25 years ago, on November 29, 1995 I visited the Mayan city of Tikal with two stoners before its restoration:

The stars over Tikal are frightening and bright.

I am here, on sacred land, in the jungle

Before dawn in the Guatemalan night.

The moisture and pre-morning has its smell

But I modernize the scent with smoke

From a little match to start my cigarette.

Cesar comes through the door drinking a coke.

He says he knew the others would all forget.

He won’t take me into the ruins alone.

Down the dark path, I follow my flashlight

Into the past, to where time has made its home

And into the temple and sacrificial sites

Where people of belief played their cosmic part

And reached through ribs to hold high a human heart.

Many years later I went back to show my daughter but it was now open to tourists:

The exchanging of colored currency

As soldiers lounged and smoked their cigarettes

While an old woman washed clothes in the stream

Should have been enough to never forget,

But I wanted to show her so much more.

We crossed the bridge into Guatemala

And into the land of the living poor.

Skinny dogs and pigs with hanging tits wallow

In the roadside brush as we both bus by.

Not even Tikal, ancient in starlight,

In its totalitarian demise

Got the primal message exactly right

But heading home, past pack boys with a load

A twelve-foot Boa stretched across the road.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | May 19, 2020 | Featured, Politics, Travel

I distinctly remember being taught in high school that what made America great was its big heart and a commitment to democracy and freedom throughout the world. The country of opportunity met you with the words of the Statue of Liberty.

However, with America’s commitment to the IMF and the World Bank after COVID-19 still in question at the White House, I have gone back to when I thought we protected free trade as essential to the spread of democracy and freedom for the world.

Imagine if there had been no Marshall Plan and America had not aggressively led the way to rebuild Europe after the Second World War. That allowed us to create trading partners and free trade and made America and Europe free and able to prosper for the last 80 years.

In college, I was taught that free trade is necessary to build civilization. Free trade is like the blood flow through a healthy body.

I may have gotten it wrong, but I think without free trade there would be no America to “Make Great Again.”

Ten years ago, I visited Syria. The Syria that no longer exists. Entire cities have been wiped out since I was there.

Back then, I fell in love with the beauty of a pre-Roman city of Palmyra and its history.

Northeast of Damascus, it survived because it was at an oasis at the crossroads of trade routes in the desert.

Years ago, it was a burgeoning metropolis of peoples and civilizations. There were times when it was a nation-state and times when it was a city within the ever-changing powers of the region. Its independence depended largely on the prosperity opened to it by free trade.

From the beginning, America has been an oasis of natural resources, protected by our two oceans from the dictators or monarchies of the rest of the world.

As a new nation, I was taught, we became an oasis of constitutional freedom with trade between the states, to became a force in the world. Have our oceans and self-confidence become a curse now? We hear only the voice of the growing isolationism, of “America first.”

Over the last three years, it seems we have not been able to admit or see that we are falling behind and doing everything but making America great again.

I am certain I can still remember when America’s foreign policy was about keeping our oasis safe and the world safe for freedom and democracy.

Anyway, I attach these 10-year-old pictures of Palmyra. You can ride a camel there.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 21, 2020 | Featured, Travel

So, this is how I got tricked into my new unintended optimism:

With the coronavirus, we are confronted with a new “new normal” yet again. I am again surprised at how fast our world can suffer catastrophic change and how quickly we accept it and adapt and —yet again — take no notice that disaster recovery as a way of life may be in our DNA.

Yesterday, quite by accident, when I was deep in quarantine and grumpy, I discovered some old travel photos I had taken ten years ago and my mind played a trick on me.

I was thinking about how years ago, there were no security checks in our airports and how now they are an accepted part of our lives.

I noticed that each picture looked like it could have been taken today, but history makes that impossible.

Look at the picture of the sister bending to be photographed with her little brother and how instantly it was interrupted by two of their playmates who wanted to be part of the fun.

It was taken in Aleppo, a city which was totally destroyed several years ago during the war in Syria.

The second photograph is of a market in Luang Prabang at the edge of the Mekong River in Northern Laos. Since that picture was taken, Chinese civil engineers have changed the flow of the river and thus the life of that little waterfront Buddhist city.

But finally, the picture which is the cause of this my unexpected optimism:

It was taken by total accident in a street market in Chiang Mai, Thailand. I realized the surprise of an unexpected discovery:

“Everybody is looking for something-at the same time.”

All of a sudden, I was surprised by the present that I thought was the past.

The people are so alive despite their futures and their past. We put our best face forward. We are, by nature, resilient. It lives in the acceptance of people in these photographs, whether these people are now alive or dead.

It is who we are.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Sep 24, 2019 | Featured, ONAJE, ONAJE Update, Operetta, Plays, Travel

So his fool tells King Lear: ”Thou shouldst not have been old till thou hadst been wise.”

I am 72 years old today and one step further into my next life. No not the afterlife… the next step and the opportunity of freedom which that entails. As it’s my birthday, I hope you’ll allow me this time to reflect…

I decided to start this blog several years ago to chronicle what would happen to me in retirement. I loved the practice of law, but concluded that there is a time to retire before you get in people’s way and can’t find the bathroom. I wanted to stay a little bit ahead of that curve so I got out early.

I already knew that eccentricity and determination always trumps a loss of intelligence. So this was my chance to be free to try something entirely different, but I still was not free of trepidation. Delusions of grandeur are a wonderful thing until you start to think you might act on them.

Nonetheless, I first decided I would become a “political force” as a Democrat in an entirely gerrymandered Republican district because I was very concerned about how we, as a country, were being divided by political forces and I was going to change that. This was Trump country. I raised more money than all my Republican opponents combined and knocked on almost 7000 doors for more than a half a year. I was resoundingly defeated and Trump became our president.

Because I obviously had learned nothing about impossibility, next I decided I would become a professional playwright. I bought a Shakespeare coffee mug and applied to the Yale Drama school, fully believing that I would be the oldest applicant ever accepted to Yale’s drama school. I succeeded only in becoming the oldest applicant ever rejected by Yale’s drama school. Nonetheless, I had decided this is what I wanted to do.

Obviously I had to rethink this thing again, with just a little more of my failing intelligence. So I applied to the Commercial Theater Institute (CTI) of New York for a class in producing theater. I had a plan. When the first morning of class broke up the students got lunch and inevitability they talked about what plays they were considering producing. When it came to my turn to talk I informed them I wasn’t considering producing anything. I wanted them to produce me. It worked. The impossible happened. A young producer agreed to read my work, liked it and arranged for professional staged readings in San Francisco and later in New York.

Because I had excelled in something I didn’t want to do and I had completed an introductory class in it, I applied for an advanced class in producing at the prestigious O’Neill Conference in Waterford Connecticut. I got in and there I met Sue Conover Marinello, who produced my play Onaje with great success last year in New York, and Christian De Gré Cardenas of Mind the Art Entertainment who has an amazing history of producing and also writing the music for a number of amazing operettas in New York. Both became friends.

After Sue Conover Marinello’s production of Onaje in New York, Mind the Art commissioned me to write the libretto for an operetta, Vox Populi, a comedy about the seventh deadly sin of pride, for Christian’s music. Last month, Christian and I completed the operetta in San Miguel Mexico.

Because Onaje had done so well, Sue convinced Kevin R. Free, the wonderful NYC director, to read the script. Kevin had fresh and original insights which lead to my reworking the script and his commitment to direct its next production.

The blog has become a happy travelogue. It is a history of mistakes and opportunities. It has taught me that even though I may not succeed in any of this, I’ve lost the fear of failure and each day is more fun than the last. The next step into a new thing is the hardest thing I ever do but it is getting easier with age.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 21, 2019 | Featured, Operetta, Travel

Over the last month I have been traveling. As I would go into a hotel room there was this game I played. I found I couldn’t imagine who had lived there before me. I have played this game before. I have always wondered who were those people who have looked out the same window at the same view?

Yesterday, I stayed in Mexico City for one day with Christian de Gré Cardenas, my friend and collaborator, before flying home. We were celebrating a magnificent week during which we finished the libretto and musical outline for our new comic operetta, Vox Populi (the voice of the people).

Mexico City has more than 180 museums — more than any other city in the world. (Paris, where I was earlier this summer, is second with roughly 140.) Christian and I started our day with an early breakfast, went to different museums all day, finished at 5:45 that evening, and had dinner.

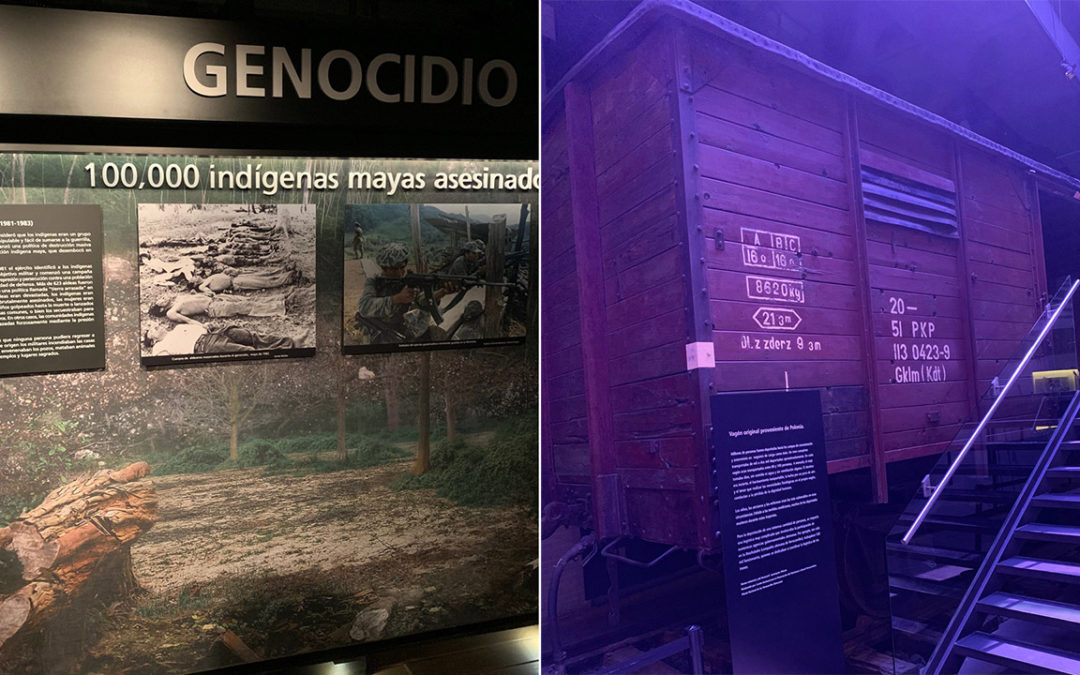

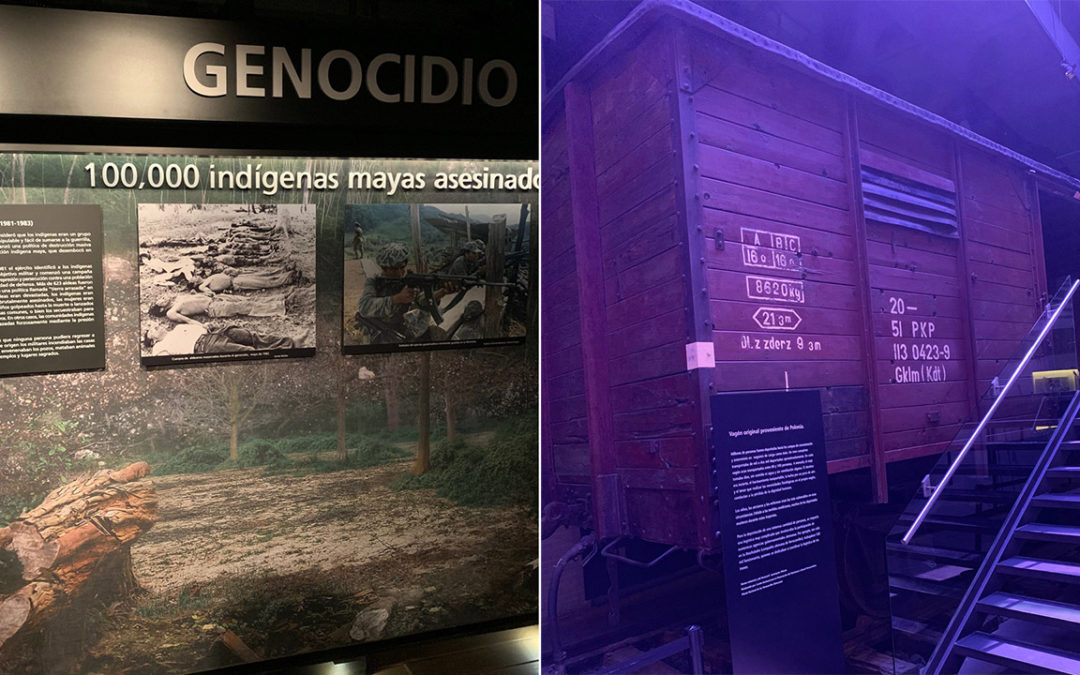

The museums have their own themes but one in particular returned me to my question about imagining the people who have lived in the same hotel rooms as I: Museo Memoria y Tolerancia, The Memory and Tolerance Museum.

Half of it is dedicated to the nightmares of humankind, but the second half is dedicated to tolerance. The first half shows, in painful detail, pictures, films, and the actual objects of genocide during and after WWII: German concentration camps, Rwanda, Sarajevo — it still goes on all around the world every day, forever.

This museum was very focused and shocked me out of my complacency on a subject that I felt I knew relatively well. How is it I only understood these numbers as the amount of times they would have filled a football stadium as a milling crowd or the number of times the population of Baltimore City?

These statistics were always there in The New York Times, The Sun, and The Post as I turn to the entertainment section or the sports page. Yet here, I walked into a small box car that carried people to the camps. I saw footage of the guns going off, the smoke, and the sacrificed falling headlong onto others in a mass grave. There in front of me was the gun that had been fired in the footage.

At dinner, as we talked, Christian read European news article on his phone, which I had missed. It said Michelle Bachelet, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, had condemned the “undignified and damaging” conditions in which migrants and refugees are being held at the US border. She called for children never to be put in immigration detention or separated from their families. She said she was appalled by the camps, and that several UN human rights bodies had found the detention of migrant children may constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, which is banned under international law.

In response, the United States threatened to stop payment of its dues unless it was exempted from the relevant UN provisions.

From the walls of that museum, the eyes looked back at me. It always starts with demonizing a selected group of people. There before my eyes the Propaganda was framed: that paper that had been circulated to the crowds and now was framed on the wall.

It always started with containment “for the public good”. Who are these people that look back at me from a museum exhibit? They must have looked out the windows at the same world I rent now.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 13, 2019 | Operetta, Travel

Is this how you make an operetta? I swear Christian De Gré Cárdenas and I are only following the charter of our employer, Mind the Art Entertainment, which requires, ”Make Art and Have Fun.”

We are five hours north of Mexico City, holed up in San Miguel de Allende, diligently working over breakfast from 9:30 to 1:30, having a little lunch, perhaps a swim, back to work from 3:30 to 6:30, and then off to the rooftop bars, dinner, local beer, mezcal, and tequila.

This is a beautiful place with deep Mexican history rooted in its independence and, in the last 70 years, the arts. In the winter, American tourists and expats flood in, along with vacationing Europeans. In the summer, far fewer visitors come and generally only for the weekends. They come here to experience the battling mariachi bands around the church plaza, the three-star restaurants at a third of New York and European prices, the stunningly beautiful textiles, art work, and wall art. Here, you walk on cobbled streets older than any in the United States and are surrounded by color.

Christian has had numerous operettas performed in NYC, most recently based on the “seven deadly sins.“ I am honored to have been chosen to write the libretto for the final operetta based on the overarching sin of “pride.”

The first day together, we went over the script I wrote over the last several months, and we just talked about it. The second day, we went to work and went line by line, page by page through the first act. The third day, we worked through the second act and celebrated the harmony of our efforts with a big lunch on a rooftop overlooking the city.

This carrying out of our corporate responsibilities is serious business. Our assignment is to write a bawdy, irreverent “meta” piece (the actors can break character and speak to the audience). It is written in rhyme and hip hop and has a singing dog.

Our first few days have been so productive, we are ahead of schedule. Tomorrow, Christian continues to outline and compose the music while I adjust and continue to shape lines and rhythms. The next several days before we leave, we will shape the two efforts into one operetta and be prepared to have it ready in the fall to be sent out to investors and performance venues.

In the meantime, over the next week, we will continue to carry out our corporate duty.