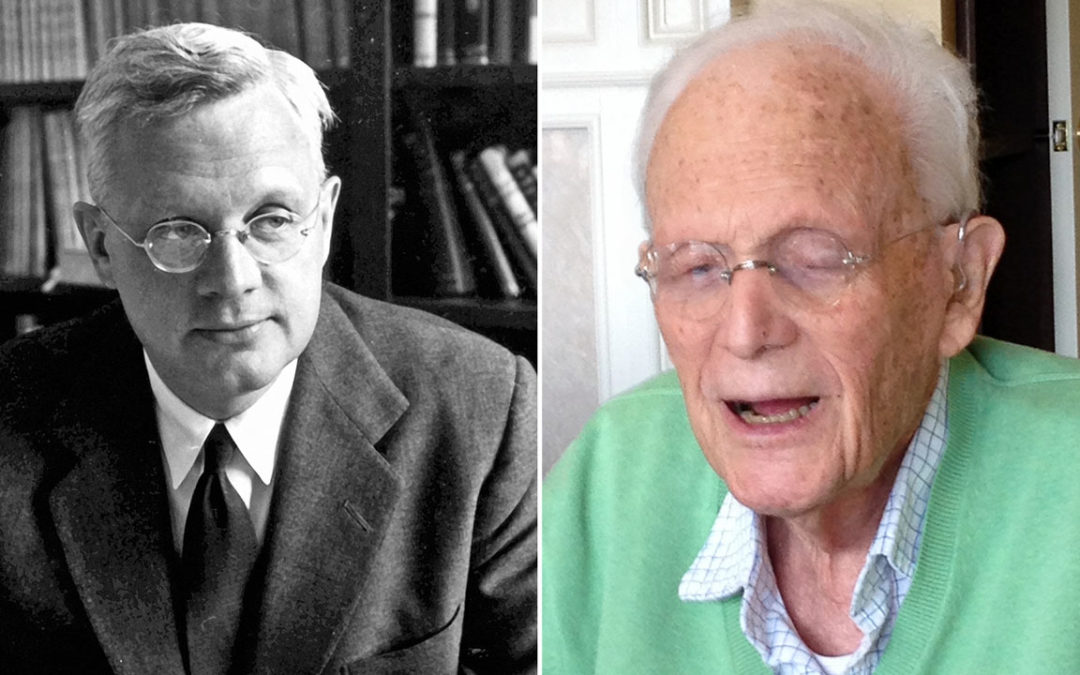

Today is my father’s birthday. He was born August 24th, 1909 and died November 2nd, 2013. Somehow my love and respect for him continues to grow. It happened over time but it is much like what Mark Twain said:

“When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.“

Imagine how “astonished” I was by “the old man” after I had continued to witness his learning as he passed 100. He set the standard. He told me one time, “I love you, but I don’t respect you.” He was right. He was always razor sharp and I grew to want his respect.

He had been first in his class in everything he had ever done and could cut through the fog to get to the heart of an issue with a single lightning bolt comment, but the real reason I thought so highly of him was I saw him choose to live with determined integrity.

During the last 15 years of his life, he lived in a retirement home near where I worked. The other old men on his floor gave up shaving for weeks but I would always shave him before he would leave his room as my show of love and respect. I would visit him every afternoon and wheel him into dinner unless I was in a trial or out of town.

In the mid-1990s, in yet another effort to win his respect, I enthusiastically informed him that this new Internet thing would open us to world peace. He smiled and said, “probably not that easy.” He was right and I was flat on my face again. I could only think of what he must have thought of me in my teens during the “don’t trust anybody over 30” period.

I was the worst kid ever. I had undiscovered learning issues back then, and well-developed disciplinary problems. I kept getting thrown out of school and — to make things worse — I would disappear to hitchhike through at least 40 of the states.

One time when I was heading back to Maryland, I called home from a payphone in a Howard Johnson’s south of the Chicago because a driver who picked me up bribed me with food if I would call my parents to tell them that I was coming home. My mother answered the phone and could not stop crying because she said she had been so worried. Despite my misspent youth, my father and mother never gave up on me. I was their son despite my failures. They would do the right thing. That determined integrity was a commitment to love. I wanted to learn that.

One afternoon when he was 94, he complained of pains in his lower abdomen and after an ambulance ride to the hospital he was admitted to surgery.

As I prayed in an empty waiting room very late at night, I thought I was never going to see him alive again. On scratch paper I sketched out a sonnet of remembrance. I wrote it after they wheeled him out of the operating room.

My Father

In the end it’s touch that holds memory.

The other senses are immediate

And defend the present territory.

The other four are there to navigate.

Tonight my father went under the knife

And I waited alone with my cell phone

To see what would become of this one life;

Together, separate, and both alone.

For an hour in the last waiting room,

I remembered him as sound and insight,

Too perspicacious for the cool boxed room

That would contain him in this, his last night.

At ninety-four how could he have survived?

I kissed the forehead of a man, alive.

As he approached his 100th birthday, we were talking and he, almost as an afterthought, said, “I admire what you have accomplish with your life. I’m not sure I could have done what you have done.” I don’t think he ever realized that was the one thing I had always hoped to hear from him. Our last years together we’re perfect. He had never withheld love. I just had refused to accept its responsibilities.

Shaving My Father

(From a draft I wrote the day after my father’s death at 104.)

This is the last small room in which he will rest.

Every day I visit him at four o’clock.

We balloon the room with our forgiveness.

“Either this man is dead or my watch has stopped.”

Two men knock on his door then wait like guests.

“Not funny for a man this close to death.”

We share what only dark humor can express.

The Marx brothers, for both of us, are the best.

The electric razor hums in my hand

As it cuts along the cheekbone and the neck.

Like a harvester on pre-winter land

I harvest thistle from earth’s intellect

Across a snow bank of thin paper skin.

They zip their bag shut and leave me without him.