by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Dec 29, 2021 | Personal, Poetry

There are so many ways to see what’s different about the same thing.

The day after Christmas we got a light dusting of snow, but it was snow!

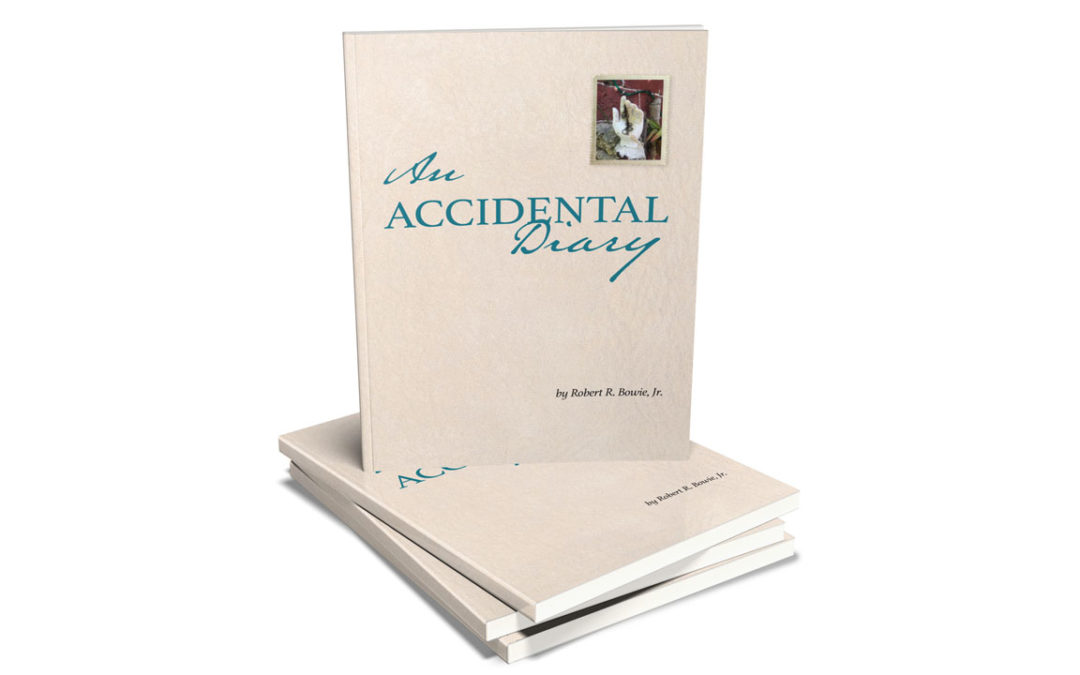

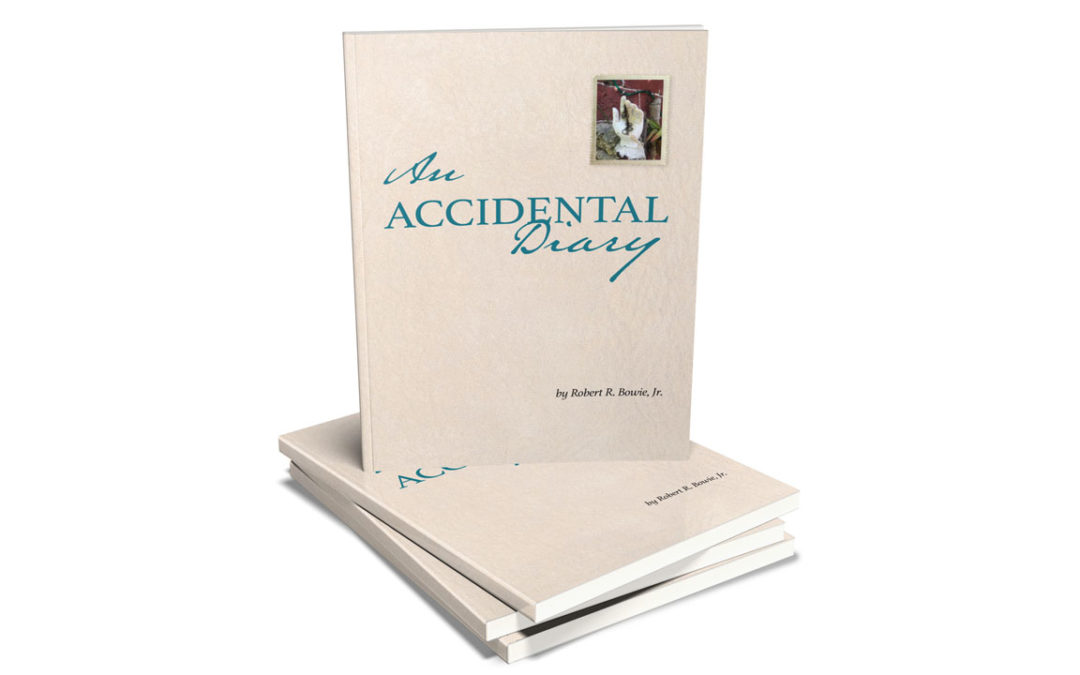

The same day I learned that my Amazon book, An Accidental Diary, was finally for sale in paperback and could be delivered by December 30th.

The hardback and Kindle have been on sale for two weeks but since Amazon prints the books they sell, the hardback wasn’t available for delivery until mid January. I couldn’t wait. I wanted to hold my book in my hands so I bought a copy.

It is amazing to learn how many different ways there are to see the same thing.

An Accidental Diary is a sonnet a week for a year, but the book wasn’t conceived of until almost 20 years later when I read each week’s entry sequentially and I discovered it really was a wild subconscious diary created over a year of transition.

It is really a game of hide and seek. It was what I had kept hidden from myself back then and what years later would happen: fond recollections and musings on loss, lust, love of family, my fear of dying alone, a sad divorce and, back then, even efforts to quit smoking.

It was drawn from a grab bag of everything in my life in order to meet a Sunday night deadline of a sonnet a week for a year. The book’s introduction defines the scope but the book does it best.

As I was waiting for my book delivery and thinking about what to write here today I looked out at the remaining snow and I wondered how this little collection of often humorous poems would introduce itself and I was amused at how the first sonnet does exactly that.

There are so many ways to see what’s different about the same thing:

City Snow

From a four o’clock sky the first snowflakes fall

To settle down on trafficked city streets.

Each snowflake falls separately, till all

Conspire to hide the city like a secret.

The last street lights go on, and the snow reflects

Upon the domiciliary landscape.

The more snow falls the less you really expect

The city to be what it’s supposed to be:

It becomes a beautiful blinking shape,

An image of slowing inactivity,

Slowing into snow drifts. It snows very late.

A pronouncement of peace subdues the city.

The drifting snow controls the city violence

With a voice made entirely of silence.

Here’s a link to get the book and give it a read if you are so inclined:

https://robertbowiejr.com/booklink/

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Dec 15, 2021 | Personal, Poetry

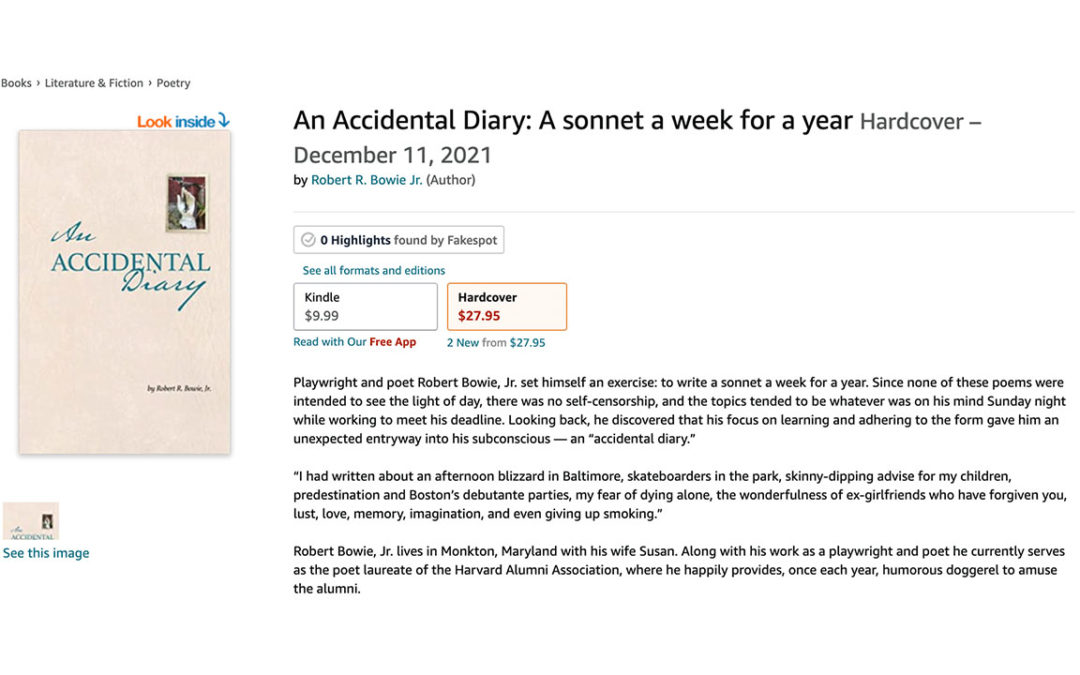

Almost a year ago I posted “Santa” as a single sonnet to celebrate the season and yesterday it became part of a book.

An Accidental Diary has been published!

Now Santa is 1/52th of “An Accidental Diary: A sonnet a week for a year.”

I am both surprised and extremely proud of my unusual book.

Yesterday, I got notice that the hardback and Kindle editions are now for sale on Amazon. The e-book version, I understand, can be read right away. The hardback is also available now, but will be delivered in January.

https://www.amazon.com/Accidental-Diary-sonnet-week-year/dp/B09NGXSVM5/

(If you’d like a personalized signed copy, reach out to me by email.)

As an old geezer I have no fear of repeating myself, so no matter what your religious beliefs may be, I offer you this my self mocking repeat, yet again to make you laugh and yet again to say thank you to each of you.

Santa

Like a massive multicolored parachute

His boxers have collapsed upon the floor

Slightly south of a wrinkled Santa suit

That was left just outside the bathroom door.

A bunch of imagined elves in repose,

Smokin’ cigarettes, feet on the table,

Hangin’ and laughin’ ’bout Rudolph’s nose

Are lovin’ life as only elves are able.

Another Christmas is, at long last, past

As the fat man shampoos in the shower

And thinks of golf and summer thoughts at last.

Who’s this metaphor for redemptive power?

An old fat guy driving a sled with gifts?

A father at midnight is what it is.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Dec 7, 2021 | Featured, Personal, Poetry

I am learning to trust and believe in random spontaneity!

Although I have been blessed with many friends, since I have committed to writing full time I have been painfully aware that I have few friends who are poets with whom I could converse.

The stars aligned perfectly last week when something wonderful happened. And then things just kept getting randomly better and better…

I had just gotten five copies of the final draft of my first book of poems, An Accidental Diary, from Kerry Sharda, my wonderful book designer. All of a sudden, the prospect of publishing became very real for me. So last weekend I took action.

I booked an impromptu trip to Boston to get advice on the book from a friend and two professors I adore about publishing this first book of poems. I then quite unexpectedly got to meet two poets I had previously never met but greatly admire.

I also had been waiting throughout the pandemic to congratulate Belinda Rathbone on her new book,

George Rickey: A Life in Balance, about the life and work of the famous kinetic sculptor.

I called Belinda hoping to meet her and get her advice but she told me that she was on her way to Scotland. After I told her about my mission, she told me that I should meet Lloyd Schwartz and Gail Mazur, both frequently published and very well respected poets, both of whom were her friends.

I jumped at this unexpected opportunity. How could this be getting better and better? I had their books and decided to bring along the most recent books of new and selected work, Who’s On First by Schwartz and Land’s End by Mazur, in the hope I could get them autographed.

We agreed to meet at Harvest, a restaurant in Harvard Square. I decided to be early but recognized Lloyd from his book cover photographs as he entered the restaurant and said, “I figured that must’ve been you because you were carrying all those books.”

Shortly after we were seated, Gail joined us and we talked for over two-and-a-half hours. We had an amazing link: We had all known the poet Elizabeth Bishop. I had only been her student once but they knew her well and Lloyd had written his PhD thesis on her and was a scholar of her works.

In addition, during our conversation I revealed that Robert Pinsky’s translation of Dante’s Inferno was a favorite of mine and Gail and Lloyd both told me they knew him and that Gail’s late husband had done the remarkable artwork for that book.

After the lunch crowd had emptied out and we finally left, Gail offered to walkover to The Charles Hotel to show me some of her husband’s works that were prominently on display as complete panels on the walls. They were as amazing as the illustrations for Pinsky‘s Inferno.

This was a remarkable weekend for me because though I love my friends I have painfully few friends who are poets.

To be surrounded by these wonderful creators as we freely talked about overlapping themes was overwhelming for me. The two were longtime friends and both agreed that creativity requires interchange and friendship to nurture artistic endeavor.

We agreed to meet again when I next came to Boston. I felt welcome and included and re-dedicated to this, my new and ever exciting profession.

It was all a spontaneous accident, which I come to believe more and more is what art and life is.

I have so much more to do.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 23, 2021 | Featured, Personal

This is the time when we gather together and stop to appreciate each other, grateful for the friends we share and the bounty of the life we have. It is a shared life on this planet.

We are particularly thankful in beautiful Monkton, where we live, and very fortunate to occasionally have wild turkeys who gather to eat the spillover bounty from the bird feeders and to visit the gardens and fields of sunflowers to eat the seeds.

Especially for them, I guess, it’s a shared planet.

Happy Thanksgiving to everyone!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 16, 2021 | Featured, Personal, Poetry

This is the story behind one of the sonnets in my upcoming book.

Sometimes you have to be far above a mistake before you acknowledge that you made it. In my case, it was flying from Belize and looking out the window more than 25 years ago.

The Blue Hole of Belize is a prehistoric giant crater which is over 400 feet deep and 43 miles out to sea from Belize City. From Ambergris Key, an offshore island east of Belize City, depending on weather conditions, it is about a 2 1/2 hour rough ride in a small Boston Whaler.

The Blue Hole was made famous by Jacques Cousteau in 1971 when he brought his ship The Calypso to the Blue Hole to chart its depth and explore its history.

Almost 30 years later, in the summer of 1997, an expedition of cave divers went in to document its underwater stalactite caves and search for its bottom depths.

Around this time, I went with several expert divers. We found it was pretty much empty of sea creatures and very cold as you descended ever deeper into it. We went down 150 feet to the nitrogen limits for 2 minutes. Our flashlights beams dimmed into the nothingness in that dark. If you looked up, far above us, the sky was like a distant open manhole cover and was our only meaningful light. After listening in the silence to our breathing for the two minutes, we ascended slowly with our bubbles to avoid nitrogen build up in our blood stream. It was very dark, cold, claustrophobic, and dangerous. Other divers had reported the same thing. After that dive I decided: “Well, been there, done that; never again.”

A few years later, when I was again in Belize to dive the outer islands, two Ambergris Key teenage brothers with a little Boston Whaler bet me a case of beer one night in a beachfront bar that if I went with them the following morning, it would be the most amazing dive I’d ever done. I refused and refused until I took the bet. This was a very stupid thing for me to have done.

In December 2018, 20 years later, two small submarines were sent to map the Blue Hole’s interior. At the bottom they discovered the bodies of two of the three divers who had gone missing while diving there over the years.

The Blue Hole in Belize

Was I the fool of this sinkhole of the sea

Or a pupil in this aqua ocean?

As I fly home it looks back at me

Without memory or emotion.

Three days ago, while taunting me, Miguel

Said: “You’ve dived it but not with me before.

I dive it deep. I dive it right to hell.”

He took my money but wouldn’t tell me more.

Off the boat, with Miguel still behind,

We checked our gear and descended into cold,

Deeper, darker, to fear of a different kind:

Sharks. Hundreds of them. Darting from the shadows.

At the boat Miguel offered a helping hand,

Laughing.” You understand? We chummed it man.”