by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Nov 26, 2024 | Featured, Personal, Shorter Stories Book

Almost 35 years ago I nearly lost my name, but 60 years ago I definitely lost my innocence.

Back in the mid-1990s, I was an aspiring business litigator who liked intellectual property. The Internet had entered the world and I reserved “bowie.com” as an email. Shortly thereafter, I got a phone call from a gentleman with a thick New York accent who asked, “Are you Robert BOWee?” I said I was Robert BOOwee. That is the exact moment I lost my name. He responded “Hello Mr.BOWee, I am David BOWee’s representative (you can look me up) and David told me to tell you that “if you will give him bowie.com he will give you front row seats, backstage passes… and all the shrimp you can eat!”

I thanked him for his interest, but demurred.

Two days later, I got a second phone call from the gentleman, who again asked me if I was Robert BOWee. I corrected him and then he corrected me back and ever since then my name was forever changed to BOWee except in Maryland and Texas.

I have been a good sport about it because, for the first five years or so, I would get email directed to David that offered “the greatest sex you’ll ever have, just meet me in the basement bathroom at Penn Station.” I am such a dork that I routinely would forward these messages directly to “Davidbowie.com,” but never once got a thank you back.

That is how I almost lost my name, but this is how I definitely lost my innocence. It’s a story from my book:

For my friends and me, life was abruptly changed on the after school athletic fields in the spring of our eighth-grade year, when all of our parents signed us up for dancing school.

My friends and I were all told it was a non-negotiable part of our education.

We were divided on the subject, until one of us confessed that in church he had recently prayed to God that he be allowed to live long enough to experience sex.

We found this to be reasonably compelling and it was sufficient to open the door for the rest of us to give in and accept the inevitable.

We had been given no previous training for this.

My preparation for dancing school was to wash my hair and then soap and rinse myself several times until I was squeaky clean, then do pull ups on the shower curtain rail in front of the mirror until I began to perspire and I couldn’t do anymore, in order to improve my physique.

Dancing school started at 4:30 pm. It was held in the middle school cafeteria at our all-boys day school. After lunch, all the tables were moved to one side, the chairs were placed side by side along opposite walls, and a piano was rolled into place.

Our instructors, Mr. and Mrs. Knot, were a husband and wife team who appeared to be in their 30s. The husband played the piano, smoked constantly, and showed no enthusiasm. We all liked him from the start.

His wife however was stern, and dressed in black high heels and a low cut black dress that featured her remarkable figure. From the start we had a problem. We couldn’t look at her, but we couldn’t take our eyes off of her.

Mrs. Knot would single out the tallest boy to dance with her. She would teach him the steps while the rest of us watched. We were then lined up with the girls from tallest to shortest and we could repeat their example.

Mrs. Knot soon showed the boys how they could politely change partners on the dance floor by tapping a boy on the shoulder.

One of the shortest boys in the class, who had big glasses, tapped Mrs. Knot’s dance partner on the shoulder in what appeared to be a shameless attempt to gain favor with his teacher. She appeared to approve, until they began to dance and she realized that her high heels and his height had placed his nose in her cleavage and his glasses were focused squarely on her breasts.

The girls were at least a head taller than most of the boys and, after a week or two, Mrs Knot announced a “ladies’ choice.”

The ladies’ choice turned out to be an extremely athletic event. The girls were choosing boyfriends but we didn’t know that.

They would slowly stand and walk toward their target, but if there was competition, they would pick up the pace and start running. There were times when two competitors, in an effort to get their boy and also to stop, would pile up and slide under the chairs where we were sitting.

The situation grew more mature. Later that spring, I had a girlfriend for almost a month, but I didn’t know that until she dumped me.

This was not unusual. Attachments were formed and broken in many cases before a boy even knew he had been going steady.

I was in my second relationship and didn’t know it until I was informed that it was over. I was told by a girl who I didn’t know that I had just broken up with a girl and that I was now available.

As the classes drifted into spring, the more adventurous girls would talk their parents into parties in the basement of their home.

They were all pretty much the same. They featured a record player and rotating chaperones to make sure nobody danced close during “Moon River.” The rule was stiff-arm dancing with visible open space between the dancers.

As the spring finished up, the chaperones and other parents migrated upstairs and gathered in the living room for cocktails. Occasionally, they would do sneak attacks or peek down into the basement to make sure the lights had not been dimmed or turned off and people were not dancing close to “Moon River.” They always claimed they were just making sure “the snacks had not run out.”

By summer, we had made friends with girls and even fallen in love and knew it.

Something beautiful had happened that spring. Nobody really knew what it was other than a transition, but it was beautifully woven together as a right of passage for everyone, including the parents.

The following spring, as upper-school ninth-graders, we would spill out of school at 4:30 pm and look in the windows of the cafeteria as Mrs. Knott waltzed her way through another dumbfounded eighth-grade class.

We had friends that were girls now, and we even knew enough to know we had girlfriends. I had even learned to do pull ups before the shower.

***

“Dancing School” appears on page 29 of The Older You Get the Shorter Your Stories Should Be, available online at bookshop.org (https://bookshop.org/contributors/robert-r-bowie-jr) and amazon.com (https://www.amazon.com/Older-Shorter-Your-Stories-Should/dp/162806420X/).

This is about self promotion before and after. Please consider buying this book and giving it as a holiday present. It would make someone very happy and also that would include me, so you get two for one!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 15, 2024 | Featured, Personal, Shorter Stories Book

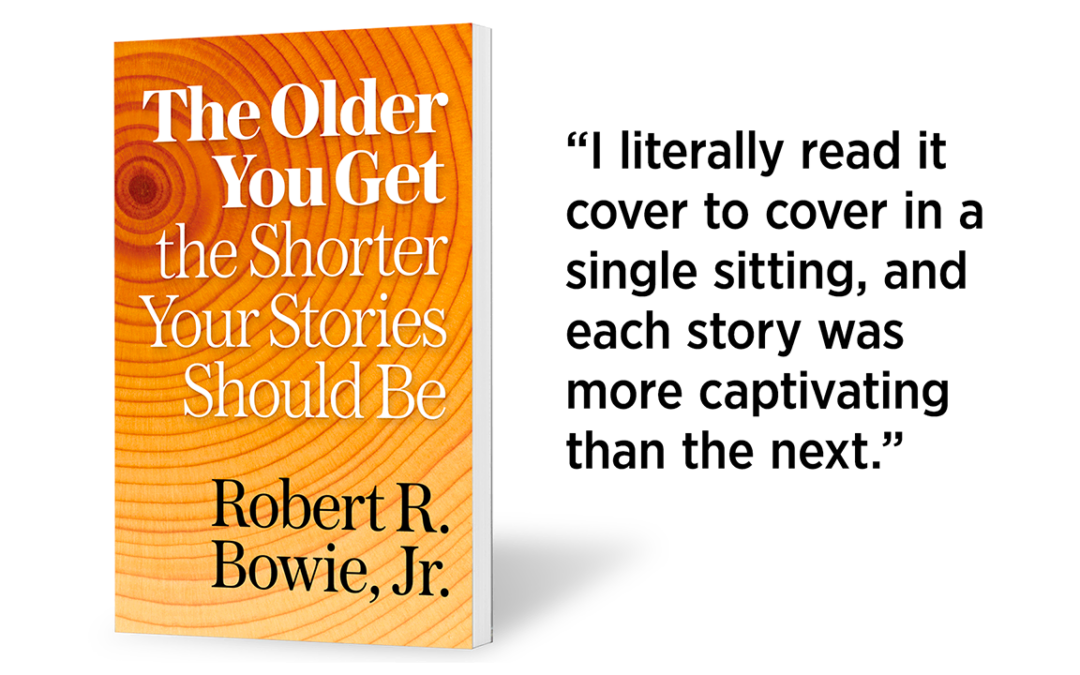

Modesty prevents me from saying anything too nice about my new book, The Older You Get the Shorter Your Stories Should Be (though I am very proud of it). Fortunately, I was able to persuade several prominent folks to read it and offer nice blurbs ahead of publication, for which I am endlessly grateful.

Now, I’ve just received my first unsolicited review and I couldn’t be more elated. This really made my week!

“I wanted to write and let you know how much I loved your newest book. Starting with its clever title, this wonderful book hooked me and reeled me in immediately. I literally read it cover to cover in a single sitting, and each story was more captivating than the next. Your insight into your surgery experience was especially compelling and your Christmas story moved me to actual tears. And I had no idea what an adventure hound you are! Or that you were Mac Mathias’s driver (the last good Republican)!

“Surely more erudite readers than I will be telling you how much they love your book, but I wanted to add my voice to the chorus of your fans. I look forward to reading whatever comes next.”

— D.R.

Thanks, so much! And thanks again to everyone who came out to help launch the book and to all who’ve picked up a copy (if you’d like your own, I recommend Bookshop.org).

If you have purchased online, writing a short review would be doing me a great favor, if you’re so inclined.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 9, 2024 | Featured, News, Personal, Shorter Stories Book

The place was packed. The readings went very well.

Thanks so much to everyone who came out to celebrate the launch of my new book, and to all who helped make the events such a rousing success. Special thanks to the Ivy Bookshop and Manor Mill, and the terrific readers who made me look good: Jenny Keith, Michael Fallon, Mel Edden, Shirley Brewer, Dan Cuddy, and Matt Horner.

You can still get a copy of the book! Just walk into your local bookstore and give them this ISBN number, 9781628064223 — they can order you one. Or you can order it online at Bookshop.org, where you can select a local bookstore to benefit from your purchase: https://bookshop.org/contributors/robert-r-bowie-f221a7ec-5949-4493-95a2-e9264cff6049. You can also find it on Amazon.

I’m so grateful to everyone who is reading these words. Thank you for your continued encouragement and support.

…

“Pearl after pearl — brief easily accessible stories that reflect the unclouded eye of the author for all things honest, compassionate and revelatory. I laughed, cried, reflected, regretted and rejoiced reading this seemingly random collection before recognizing the common thread — clear-eyed humanity. Mr. Bowie’s curation of his self-deprecating, poignant and often hilarious moments, will become a dear friend whose warmth and comfort are there to visit again and again!”

— Ty Cobb

Prominent Washington, D.C. lawyer and former White House Special Counsel

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 1, 2024 | Featured, News, Personal, Shorter Stories Book

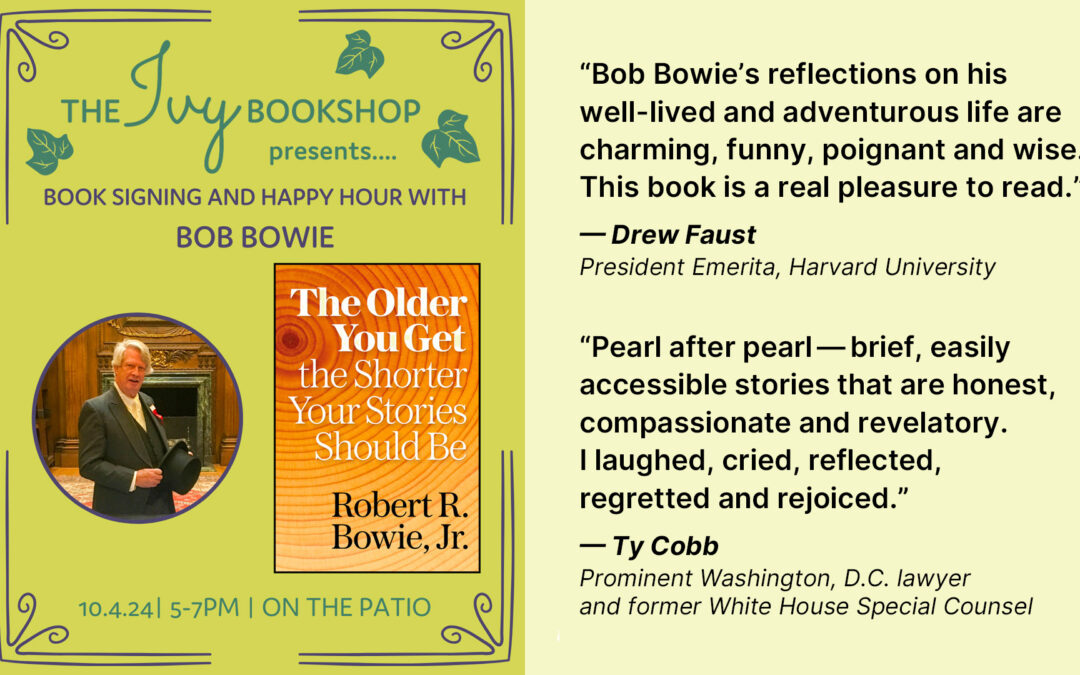

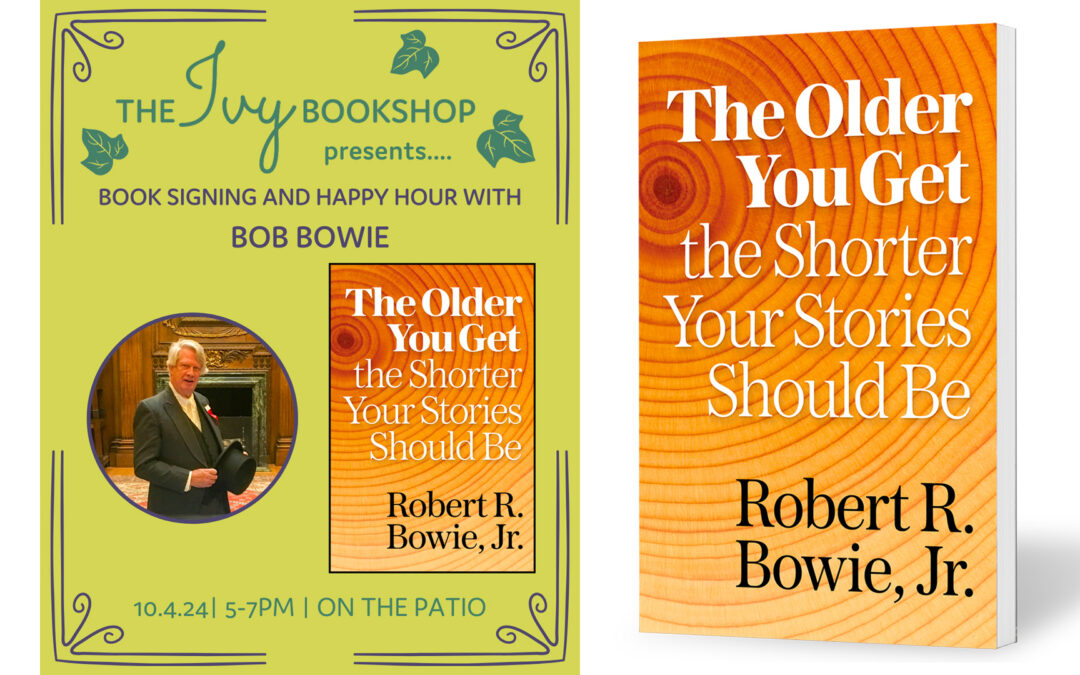

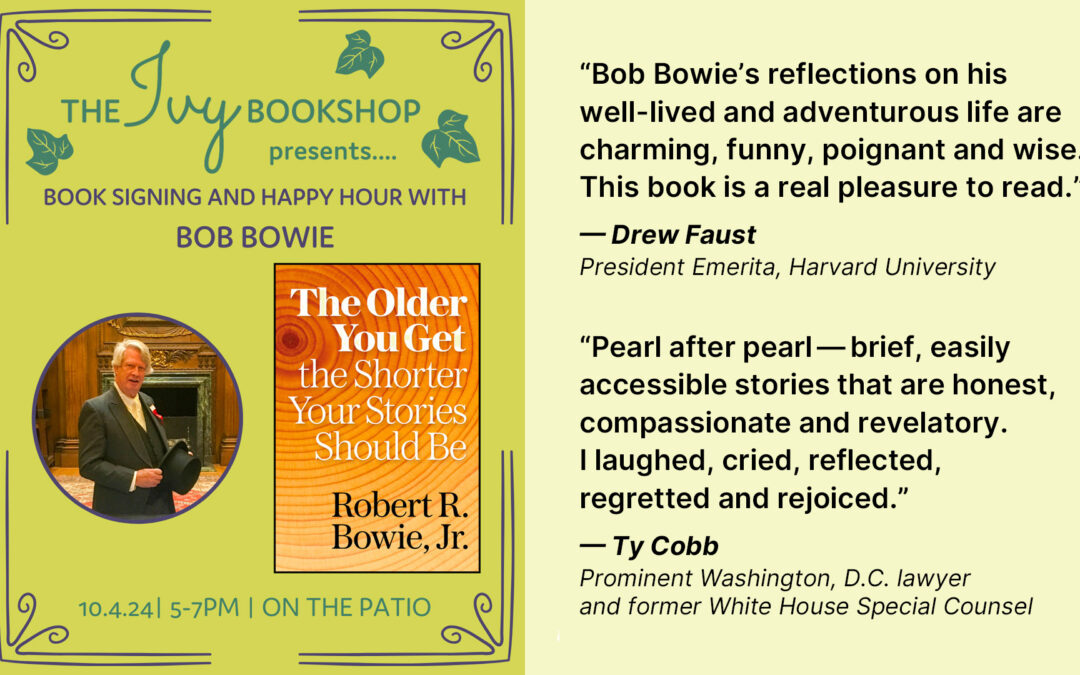

This Friday! Please join me for a special launch celebration at The Ivy Bookshop in Baltimore, October 4th from 5:00–7:00 pm. There will be cocktails on the patio followed by a reading and book signing.

Helping me read selections from the book are the following distinguished Maryland poets: Jenny Keith, Michael Fallon, Mel Edden, Shirley Brewer, Dan Cuddy, and Matt Horner.

The Ivy Bookshop is at 5928 Falls Rd, Baltimore, MD 21209.

We’ll also be gathering on Sunday, October 6th from 4:00–5:30 pm at the Manor Mill, 2029 Monkton Rd, Monkton, MD 21111 with the same amazing lineup of terrific readers.

I hope you can make it. I look forward to seeing everyone there and signing any books that you purchased.

(If you can’t make it, the book is also available online at Amazon and bookshop.org.)

…

“Bob Bowie’s reflections on his well-lived and adventurous life are charming, funny, poignant and wise. This book is a real pleasure to read.”

— Drew Faust

President Emerita, Harvard University

“Bob Bowie has written a riveting and rollicking collection of tales comprising his life as a Renaissance Man who overcame serious childhood learning disabilities to become a Harvard Poet Laureate, adventurer, lawyer and playwright. Writing with brutal candor and self-deprecating wit, Bowie unspools stories that both entertain and pack plenty of wisdom. I thoroughly enjoyed this book.”

— Ben Bradlee, Jr.

Pulitzer Prize-winning Editor of The Boston Globe Spotlight Team

“Pearl after pearl — brief easily accessible stories that reflect the unclouded eye of the author for all things honest, compassionate and revelatory. I laughed, cried, reflected, regretted and rejoiced reading this seemingly random collection before recognizing the common thread — clear eyed humanity. Mr. Bowie’s curation of his self deprecating, poignant and often hilarious moments, will become a dear friend whose warmth and comfort are there to visit again and again!”

— Ty Cobb

Prominent Washington, D.C. lawyer and former White House Special Counsel

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Sep 25, 2024 | Featured, News, Personal, Shorter Stories Book

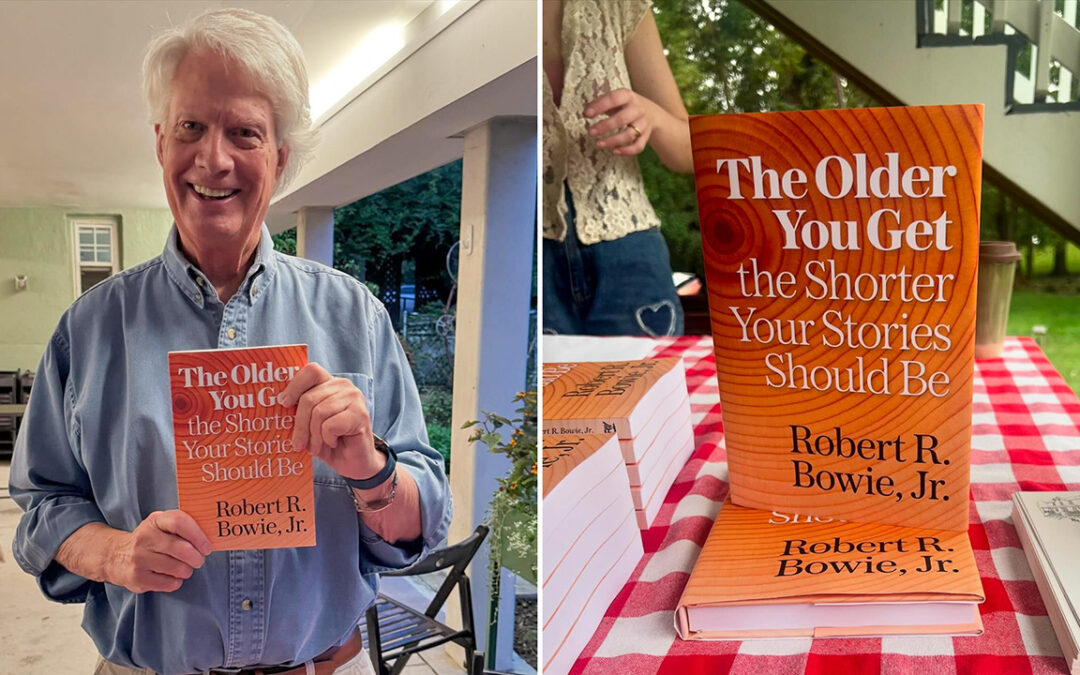

As of yesterday, The Older You Get The Shorter Your Stories Should Be is now in print. What a great present for my birthday!

Please join me if you can for a special launch celebration at The Ivy Bookshop in Baltimore on Friday, October 4th from 5:00–7:00 pm. There will be cocktails on the patio followed by a reading and book signing. Books will be available for purchase there (and I’d love to have you help support the Ivy).

The Ivy Bookshop is at 5928 Falls Rd, Baltimore, MD 21209.

We’ll also be gathering on Sunday, October 6th from 4:00–5:30 pm at the Manor Mill, 2029 Monkton Rd, Monkton, MD 21111,

You can find the book for sale on Amazon and at Bookshop.org, where you can select a local bookstore to benefit from your purchase: https://bookshop.org/contributors/robert-r-bowie-f221a7ec-5949-4493-95a2-e9264cff6049

(You should also be able to ask your local bookstore to order you a copy by providing this ISBN number: 9781628064223.)

I’m so proud of this book and can’t wait for everyone to enjoy it.

…

“Bob Bowie’s reflections on his well-lived and adventurous life are charming, funny, poignant and wise. This book is a real pleasure to read.”

— Drew Faust

President Emerita, Harvard University

“Bob Bowie has written a riveting and rollicking collection of tales comprising his life as a Renaissance Man who overcame serious childhood learning disabilities to become a Harvard Poet Laureate, adventurer, lawyer and playwright. Writing with brutal candor and self-deprecating wit, Bowie unspools stories that both entertain and pack plenty of wisdom. I thoroughly enjoyed this book.”

— Ben Bradlee, Jr.

Pulitzer Prize-winning Editor of The Boston Globe Spotlight Team

“Pearl after pearl — brief easily accessible stories that reflect the unclouded eye of the author for all things honest, compassionate and revelatory. I laughed, cried, reflected, regretted and rejoiced reading this seemingly random collection before recognizing the common thread — clear eyed humanity. Mr. Bowie’s curation of his self deprecating, poignant and often hilarious moments, will become a dear friend whose warmth and comfort are there to visit again and again!”

— Ty Cobb

Prominent Washington, D.C. lawyer and former White House Special Counsel

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 18, 2024 | Featured, Humor, Law, People, Personal

As I have said before, I loved representing entrepreneurial business clients because they are crazy.

The little cases are always the funniest and the easiest to tell.

He was a general contractor who built big shopping malls and was always very gruff, extremely overweight and endlessly funny. He, his wife and I, became friends over time and my professional responsibilities merged into our friendship as we got to know each other.

After making a lot of money building shopping centers and stocking them with commercial tenants, he decided to design and build his own mansion. He bought two adjoining lots in a suburban cul-de-sac, and designed what his wife described as “a Las Vegas hotel — not only embarrassing but gauche.”

In his mansion, he determined that he wanted a large indoor fountain, as well as special toilets for his and his wife’s bathrooms. These toilets would protrude from the wall, but have no base onto the floor because he thought that was classier.

He had absolutely no sense of taste.

He battled with the architect who said that these toilets could not withstand his weight and were not classy just because they came out of a wall and didn’t have a base.

She succeeded in vetoing the lavish indoor fountain, but he won the battle in their matching bathrooms with the “extended toilet” from the wall, which had no connection to the floor.

I was his lawyer but we made each other laugh. As I was thinking back on him, I remembered defending him in a lawsuit many years before he built the mansion. He had put a roof on a tenant’s building and the tenant had decided to represent himself because he thought he knew everything about construction and could litigate better than any lawyer.

It was a little non-jury case to be tried in a packed courtroom full of lawyers and clients waiting for their cases to be called. Trying a case in a court at this level is like litigating in a circus tent a head on collision between clown cars — particularly if a defendant or plaintiff comes to represent themselves. The judges at this level have a rotating docket consisting each day of either misdemeanor, criminal, petty civil or traffic court.

I knew the judge socially. He had developed a sense of humor after too many years presiding over these petty cases and traffic court.

The plaintiff in this case argued that the “neoprene” roofing materials had been inadequate, and he was going to be his own expert witness to prove it. The plaintiff was a buffoon who didn’t know what he was talking about. It was a little case that would cost more to try than settle. The client decided to try it “on principle,” which is always a problem. He told me, “I don’t care if you win or lose, just make me laugh.”

I decided to go for broke. After the plaintiff announced that he wanted to be his own expert witness, I decided I would cross examine him on his qualifications before the judge ruled on whether he could be considered as an expert witness on roofing materials.

I asked him if he knew of the latest advancements in “neoprene” roofing materials. He clearly was uncertain but proclaimed he did. I had him hooked. I carefully asked him if he had ever heard of the new “Neofeces” roofing materials.

He said that he had. I spelled it out for him so he could be certain. He cautiously said he was certain.

So now I was crossing him on Neo (new) feces (shit) roofing materials. Clearly you could feel the courtroom saw entertainment in its future.

I asked him if it bothered him professionally that “neo-feces“ was still regrettably not yet odor free. He claimed it did not. I asked him whether he agreed that double-ply toilet paper was considered sufficient for the removal of “neo-feces.” The courtroom rustled as those watching started to follow the tightening of the noose.

After one or two more questions inquiring about the benefits of “neo-Feces,” I paused between the two words and the courtroom started to laugh a little but the witness did not. At this point, the judge stopped me to preserve order in the courtroom and instructed me that I had made my point and had “won the pot with a royal flush.” This was appreciated by all those still waiting to try their cases, as well as the backbench court watchers.

About a month after my client had moved into their new opulent mansion, I got a call from my client’s wife at around 11 o’clock on a weekend night.

She started the conversation by saying that I must come over immediately because she could no longer talk to her husband, who was presently lying on his back on his bathroom floor laughing hysterically.

Apparently, after a night of much beer and football on the super wide screen, he had sat down on his toilet and it had broken off, and he kept slipping and could not stand up because there was water shooting all over the bathroom. I told her I would contact a plumber to turn off the water and then I would be right over.

I asked her, “How bad was it?” She paused on the phone for one second and then just said, “Let’s put it this way, the goddamn toilets he wanted didn’t work, but that’s okay cause he got his goddamn fountain!”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 11, 2024 | Featured, Humor, Personal, Politics

Have you ever just stopped in the street and said to yourself, ”Wow, I wish I had that to do over!” and then found yourself exploring even larger questions?

Because of my short-lived political background, I ponder irrelevant questions and worry about them all the time.

I have some regrets.

For me it all happened back in 2014, but it only became clear what my concern should have been about two weeks ago.

Back in 2014, I was asked a question that I couldn’t answer. That was the problem.

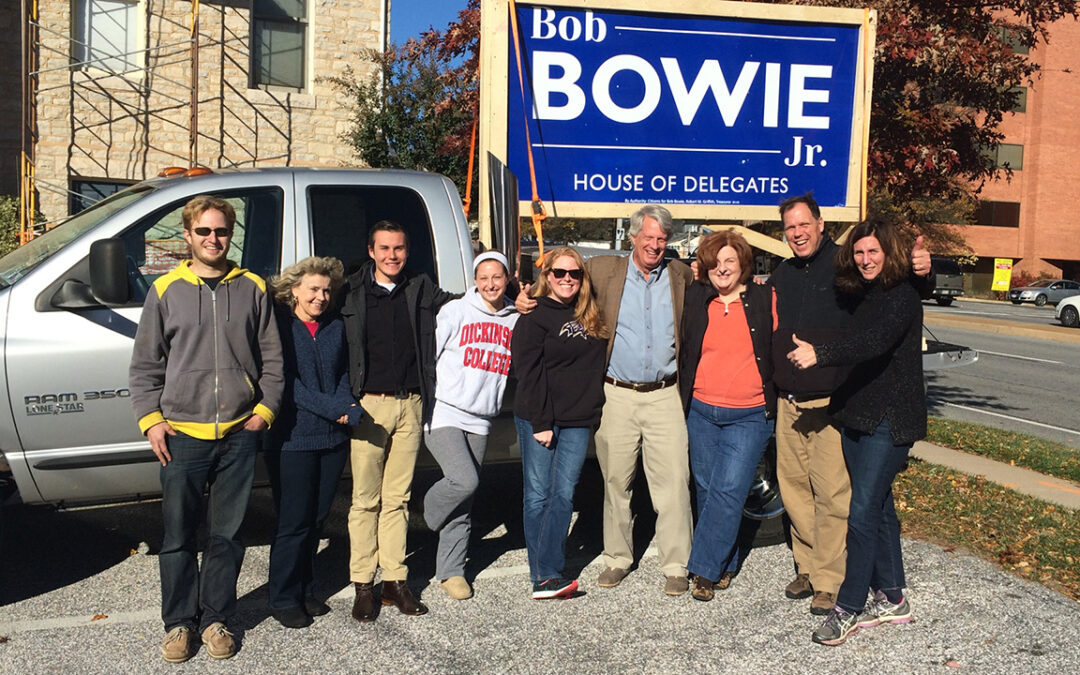

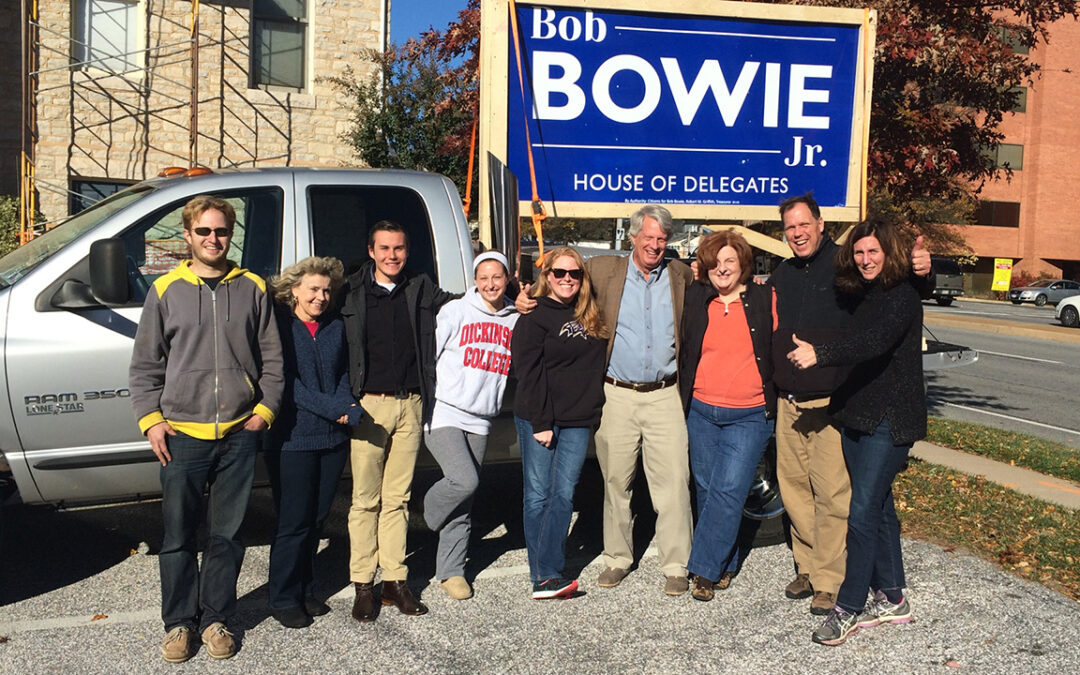

Back then, I hated gerrymandering and concluded that the country was getting dangerously divided because of it, so I ran for political office on a theme that ”We must not lose our common ground.”

My strategy would be to find common ground with every person in my divided district and thus bring them together so we could reason together.

Maryland is two-to-one Democrat and the state legislature had crammed as many Republicans as possible into the district where I lived. I am a Democrat but I was sympathetic to my outnumbered Republican neighbors. I consulted the experts and was informed that I had at best of five percent chance of winning as a Democrat in this district.

I jumped right in!

I really believed I would win if I could find some common ground each time I knocked on another door.

I was all in. I contributed my own money to the campaign and I raised over $150,000. Susan and I and a small group of overoptimistic diehards spent that summer and fall knocking on 5000 doors, and debated the three incumbents who raised only around $5,000 together. They did not need the money. They had all been in office for over a decade in this gerrymandered district.

Late one hot summer Sunday morning, it turned out I didn’t know “ common ground” as well as I thought I did. Only about two weeks ago, did it all became clear.

When I knocked on the doors, I always had the same pitch: ”I believe we must find our common ground so we can all talk together.” Then for humor I would add, because I was over 65 years old, that ”if they were worried about term limits, nature would take care of that in my case.” Everybody laughed, and we talked as friends until I was asked whether I was a Republican or a Democrat, at which point the door was slammed in my face.

Of course, I remained optimistic. As I would drive home while the sun was going down, I believed the depth of my commitment would pull me through.

The depth of my commitment was only challenged once, when I could not find “common ground.“

Late in the August heat, I knocked on the door of a well-kept home in a trailer park, which had three steps on either side of the front door.

I knocked on that door and a heavyset woman dresses in a giant muumuu answer the door and after my pitch she announced: “I can’t talk to you right now because I don’t have any underwear on.”

How was I to answer that? For the first time maybe ever, I was speechless.

I couldn’t say, “You don’t need to be wearing underwear to read my materials,” or, “No problem I’ll wait til you put on your underwear.” I was dumbfounded. I could find no common ground.

For almost ten years, I have pondered this interchange. I thought and rethought about my inability to find an answer. I have not hesitated to tell this story to others in the hope that they might suggest something. Then about two weeks ago, a friend of mine had an answer right off the top of his head!

He said, “You forgot your theme. Why didn’t you just say, “That’s okay, I don’t either!”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | May 28, 2024 | Featured, Personal, Poetry

I’ve always been a little shy about confessing my love of poetry.

Over 40 years ago, my love of poetry got into a head-on collision with my decision to be a successful lawyer. This collision was the final confirmation I needed to reenforce my belief that I should probably keep my mouth shut about poetry.

This year, however — in fact, this spring — I have outgrown this conclusion once I appreciated the humor in my mistake and that I wasn’t the center of the universe, which is probably why it took over 40 years.

On Saturday, June 1, in less than a week, we will be celebrating “Poetry Day” at Manor Mill in Monkton, Maryland. Manor Mill is a beautifully reborn pre-revolutionary gristmill on a little tributary off the Gunpowder River. There, Angelo Otterbein, its new owner, has created a center for the creative arts in the middle of the verdant horse country of northern Baltimore County.

For the last year and a half, on the first Monday of every month, Mel Eden and I have run a poetry open mic at the Mill. We start at 6:30 pm with a reading by one or two well established mid-Atlantic poets. Then, after a brief break, we turn to the open mic sign-up sheet, with each poet sharing one poem each, providing a wide variety of work. Then, if possible, we do a second round so each poet has an opportunity to read twice.

This group has grown into an ever increasing source of inspiration and community for both established and upcoming poets from all walks of life. From the beginning, we also set up a poetry class at the nearby Hereford Library for new poets to perfect their chops before they elect to perform. This class has been led by Michael Fallon, a celebrated retired professor of poetry who has taught and published for over 35 years.

Poetry Day on June 1st was created by Mel to celebrate this new artistic community as well as the art and creation of poetry. Mel is also largely responsible for a beautiful professionally published bound book of Manor Mill open mic poems and poets that is scheduled to be available early this September.

Back to my head-on collision, though, which years ago separated my two passions and broke my fragile poet’s heart.

All through law school on Saturday nights I didn’t go out drinking with my friends. Instead, I would cook a Cornish game hen, drink whiskey and listen to one of my extensive collection of recordings of Shakespeare plays.

I kept this eccentric behavior to myself for the most part, except in my second year, I met a Baltimore Sun reporter, Carleton Jones, at our local Maryland Institute of the Arts art student bar, which featured big display panels on the walls where artists were offered a chance to display their work.

Carleton was in his early 70s, I would guess, and it turned out one night we both confessed our love of poetry. Without my knowledge he went to the owner and I was offered a chance to post my poems on the large panels in the bar, normally reserved for art and thereafter Carlton wrote a glowing review in the Sun.

I almost came out of the closet and admitted to myself that I was a poet until an all-important second job interview at a large law firm broke my heart and I went underground again.

In hindsight I was foolish and easily injured but it is funny, so here goes:

At this interview, four lawyers and a senior partner went over my resume and asked me questions until the senior partner took control. I took this as a good sign, particularly when he pointed out that at the end of my resume under “Other Interests” I had included “poetry.“

He asked me, “What is the difference between poetic writing and statutory writing?” I took this as a great final line of inquiry!

“Okay,” I said. “If you want to write a statute to prohibit throwing up on the street you would say, ‘No throwing up on the street’ and then define ‘throwing up.’ But if you were Shakespeare you would say, ‘speaking with a full flowing stomach.’”

I could not have been more excited to be so erudite on a subject I felt I knew quite well, so of course I couldn’t leave it alone.

“If you wanted to forbid fornication,” I continued. “You would write a statute prohibiting fornication and then define fornication, but if you were Shakespeare, you would say, “Making the beast with two backs.’”

I was a little surprised when the senior partner announced that the interview was now over and they would be in touch.

As I went down the elevator I was very proud of myself, but as I walked home the doubt came on slowly. By the time I reached my neighborhood bar, I went in and had a double scotch.

A couple of days later, I got a letter, and jumped to the conclusion that they thought I might not fit in. They wished me well on my future career as a lawyer.

To this day, I remain a proud (now retired) lawyer but I’m now proud to call myself a poet, too.

Thanks to Manor Mill, I have been around poets nonstop for the last year and a half and I have been welcomed. I have made wonderful, lifelong friends and have come to believe that perhaps Mel and I have encouraged future poets to find their voice and sing. These poets are remarkable people. They step out of the grind and observe it for others. They are fun to be with.

I hope you can join us for Poetry Day on Saturday and see for yourself. There’s a full schedule of events at www.manor-mill.com/poetryday.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 30, 2024 | Featured, Personal, Travel

As we have walked around Paris you can feel the pride everywhere as the city prepares to host the Olympics. That pride is always there but perhaps now it is heightened, most evident in the city where you see the care and detail in the retail efforts. Whether they are the cafés, cheese mongers, or street markets full of fresh fruits and vegetables and fresh cut flowers, there is artistry in the display and even a little bit of competition between the storefronts. They are always careful and creative but some are so odd and distinctive you stop and join the fun.

I stopped by this statue with an indented empty bronze face (even though the photo makes it appear to protrude). Other statues behind the windows sit or stand and have the same hollow faces, empty but with no bronze. To the left is a paint can supported on a base made to stay in place by what it has already poured. Gold medal!

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Mar 26, 2024 | Featured, Personal, Travel

Several weeks ago, my son and I went to Orioles spring training in Sarasota. I was careful to take lots of pictures, but after our last game it was odd how my thoughts unexpectedly returned to a trip I had taken earlier this spring. I was on a tour that followed where civil rights activists had marched 60 years ago from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in March of 1965, where they were mercilessly beaten as they tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

This abrupt transition probably did not take place for the reasons that you may imagine.

The Orioles played well and won most of the games that we attended. No, it was something other than that.

It was about living rather than photographing life, and what gets lost and what gets saved.

The Ed Smith Stadium, where the Orioles are encamped for spring training, holds less than 7,500 people. It is like watching Little League compared to Oriole Park in Camden Yards in Baltimore, which seats about 46,000.

The ushers that take you to your seats are all Baltimore retirees, snowbirds bright with their orange uniforms and big smiles. It is magical. The team prepares for the future in a library of memories in the Florida sun.

Our first game, we sat behind home plate and watched the field being lined as the seats filled up around us. It reminded me of when my children were young and we would go to minor league games in Frederick, or even to see the Bowie Bay Sox.

I’ve got the pictures to prove it.

Sitting behind home plate in the afternoon sun, we were up so close we could see how a 90-mile-an-hour fastball looked and sounded when it snapped into place in the catcher’s mitt.

The second game we were behind the Orioles’ dugout. You could see the faces of the players and read their expressions in a way that big league baseball cannot reveal on TV. The cell phones were all focused and the cameras were taking pictures.

Every other day, when the Orioles were traveling, we went to the beach. It was worthless to try to photograph and capture the enormity of going to the beach. The sand was bedroom slipper soft, and the sky was bright blue and huge. Shore birds flocked and fought for food scraps as people packed up, left the beach and went home. You just had to experience it with the sound of the waves and the bickering of the birds.

A photograph could not have captured the environment for memory. Without context, it was all too big and undefined to be described.

The night before we went home, we chose seats by the left field fence at the foul line.

We sat next to a young boy who desperately wanted to catch a baseball in his glove, which he kept squeezing and squeezing to our left. My son, who is a college football coach and had been a fourth-grade teacher, knows and loves kids this age.

As the players warmed up in left field between innings, we all got into the act as the players warmed up. We all were trying to get a player to give the young boy a baseball.

My son was quiet for a while until he encouraged the boy to get the ball himself. The boy’s older brother and father grew suspicious. My son encouraged the boy to leave the rest of us behind and go past the left field foul line to where the bullpen was located. There, he could watch the catcher and pitching coach as they were warming up the relievers between innings.

The boy went off on his own but we all could see the interaction between that determined young boy and that aging catcher and pitching coach because it was palpable, but still professional.

On his own, the boy built up his courage and made distant contact with the catcher and ultimately, at the end of the game, the catcher handed the pitching coach a ball, pointed at the boy, and the pitching coach went over and delivered the ball to him. All this was watched with bemused approval and excitement by the local crowd who had followed the little drama.

As we were walking back to the car after the game was over, I chastised myself for not taking pictures as the little story evolved. I remember the amazing joy on that boy’s face as he pounded and re-pounded the ball in his glove as he said goodbye and we went our different ways.

I remember from my tour reading the history of the march from Selma as I started across the bridge and over the brown river with its high banks, which I photographed excessively until I stopped midway across the bridge.

All the photographs I had taken were of a bridge before spring, where there was little life along the shoreline up and down the river. All of a sudden, I stopped photographing, and just looked and felt the river flowing beneath me. I imagined what the crowd must’ve felt with the locals and their law enforcement ready to beat the daylights out of the marchers if they moved a step further and they did.

I go over those photographs now, and I don’t catch the event the way I remembered it by looking at it and avoiding the photograph. I feel the same way about seeing that boy pounding that ball in his glove and smiling as we parted. Without context, it was all too big and undefined to be described. The memory may fade, but because I didn’t take the photograph, I saw it and the experience is still alive in me.