by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Oct 3, 2023 | Featured, Personal

Recently, as I waited to exit a Southwest flight in Baltimore, a fellow traveler — who also turned out to be a fellow retired lawyer — laughed and asked me whether retirement had changed my life much, or perhaps had even changed my view of humanity.

The two of us had met and decided to sit together in the Boston airport while waiting to board from positions A-1 and A-2 for business class seating.

Now we both were waiting patiently to exit from the middle of the plane because the 22 wheelchair-assistance passengers who had pre-boarded would be exiting from their aisle seats, which they had taken when they entered the plane.

I decided to answer the two questions separately. First, I told a brief story to illustrate what my life was like as a practicing lawyer:

One afternoon around 4:00 o’clock while I was actively practicing law years ago, I developed chest pains. I was on the phone with a witness for an upcoming trial, so I decided that I would finish the call before I dealth with the pain in my chest.

After the call, I decided to try hanging off a door to ease the pain.

I found a door that was part open, put my hands on the top, and hung from the door to see if the pain would go away. Ater a while it did so I went back to work.

Later that night at dinner with my wife and children, the pain returned. I didn’t want to trouble anybody, so I left the dinner table, found a door and hung off of it for a bit until the pain subsided again. Then I flushed the toilet for cover and went back to dinner.

But later, around 1:00 o’clock in the morning, the pain returned. I got out of bed to find an open door somewhere in the house. My wife woke up, rolled over, and saw me hanging from the bedroom door. She told me to go immediately to the hospital.

However, when I went into the closet to get dressed, the only clean shirt that was readily available was a white shirt just back from the dry cleaner. I put it on and looked for a pair of pants. I found only a suit, which I immediately put on and then I was stuck with a problem. I couldn’t possibly go in a white shirt without a tie, so I just reached into the rack of ties and put on the first one I grabbed. I didn’t turn on the light because I didn’t want to wake up the house, so I didn’t even know what color it was.

Finally, I got lucky. I had no problem tying the tie in the dark.

It was about 2:00 o’clock in the morning and the roads were empty as I sped down the highway toward the nearest hospital. The pain was getting pretty bad and for the first time it occurred to me I might die.

In that moment in the dark, my mortality became very real to me. I concluded I might never leave the hospital.

It was a remarkable revelation for me, so I reached into the glove compartment and pulled out what I considered would probably be my last cigarette.

At the emergency room parking lot, I started to get out of the car, but realized that my briefcase was in the passenger seat next to me. I was concerned that there were confidential papers belonging to my client pertaining to the trial that were in that briefcase so I brought the briefcase with me into the emergency room and politely let the nurse know that I was having chest pains.

Before I knew what was happening, I was being pushed back into the seat of a wheelchair with my briefcase squarely riding on my lap and then wheeled at a high rate of speed toward cardiac care by a nurse in the night time hospital. She patted me on the shoulder and asked in an exasperated voice “So you think you might have a heart attack at 2:30 am and be back at the desk by 7:00?”

Well, the nurse overreacted. It wasn’t a heart attack. It was just gallstones that nearly killed me, but I had been right, hadn’t I?

As my story ended, we began to move down the aisle and exited the plane. Gathered by the gate were almost 20 wheelchairs. None of them had been used to take any of the passengers into the airport.

My traveling companion and I both laughed good-naturedly. “So, what about my second question,” he prompted. “Has your view of humanity changed?”

“It’s all how you look at things,” I replied with a wry smile. “Isn’t it wonderful that Southwest doesn’t charge extra for miracles?”

We laughed, then hurried to our next transportation.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Sep 7, 2023 | Featured, HAA, Humor, Poetry

Hopefully this will make you laugh.

This is the year of my 50th college reunion and here is my ode about what I think about that.

–––

The 50th Reunion of the Class of 1973

(and a Tip of the Hat to the Class of 2023)

So is this where sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll ends?

With grandchildren, prostate problems and Depends?

Not for the class of 1973

On this, our 50th anniversary!

We’re the Alums that never stopped having fun…

For us our college years were just a dry run

So why try to remember what I’ve forgot?

Maybe it’s a little. Maybe it’s a lot.

Who cares? Fifty years of paranoia

Now pot’s legal’n, some say, even good for ya.

Forget that thought that we are all old relics.

Now shrinks treat patients with our psychedelics.

Memory and “smarts” never go hand in glove.

I’ve no memory of what my major was.

Who cares, long as they don’t take my diploma back

If my “memory lane” is a cul-de-sac!

I do still remember my graduation!

That 50th, class of ’23, had some fun!

And that is one thing that I’ll never forget.

Them dancing to James Brown, I really regret.

I’ll tell you the whole truth. I will tell you no lie.

Wasn’t exactly “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.”

Man, we lived through some stuff you just can’t forget:

Watergate, Berlin Wall, and the Chia Pet.

But wait! Just stop and wait. I wonder what we

Look like to the grads of 2023?

They’re so advanced I check for hair on my palms.

They have evolved so much! They’re truly phenoms.

I still type with both hands and I feel very dumb.

Darwin was right. Now they can type with their thumbs.

Oh, but we’ve got wisdom in the class of ’73!

First, you must accept Harvard’s study on longevity.

It is not your new Harvard degree or your new PhD.

Joy comes from your classmates, and your friends and your family.

Second, the older you get the shorter your stories should be.

And last, “Peace ’n Love!” from the great class of ’73.

–––

For the last 10 or so years I’ve been a poet laureate. I love the school, I love my class, and I love my classmates, and all I have to do to keep the job is hope the alumni laugh. This is a very prestigious job which pays nothing and thus has made me irreplaceable.

Visit https://robertbowiejr.com/haa/ for further hometown skulduggery.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 22, 2023 | Featured, People, Personal

Many of us in our joyous misspent youth, particularly in our teenage years, enjoyed the undisciplined fun of our juvenile hubris.

Hubris is an ancient Greek word that describes excessive exuberance, confidence, or pride, which can often bring about one’s downfall.

The art of teaching teenagers during the hubris years requires a middle path, somewhere between crushing the hubris and leaving it untethered. This middle path requires the difficult task of helping a student to channel hubris to promote individuality and personal growth, because this youthful burst of enthusiasm often can be the first sign of what a young person’s real interests really are.

Think of the people you know who discover that they hate their careers in midlife and go in an entirely different direction or, worse, don’t.

My experience is that many of these people were not educated to question and challenge their conclusions. Rather, they were educated to take good notes and vomit it all back on the final exam to be rewarded with a great grade, and then passively step into careers in which they were never really interested.

Whitney Haley, our drama teacher at the Cambridge School of Weston, was a master of the middle path. He marshaled his resources and directed us with surgical, gentle humor.

Whitney was an aging, portly diabetic, who had long ago retired from a career in the silent movies. He did everything with an intentional dramatic flair. He pronounced his name with one hand dancing in the air as Whit-Née (brief dramatic pause) Hay-Lée (and then wait for our response). He herded us with humor rather than a cattle prod. Everybody loved Whitney Haley!

In our high school play, I was cast in the role of John Hale, the strict Puritan minister, in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. Before opening night, we all applied our own make up, which was approved by Whitney before we went on stage.

I came to the conclusion, as I was putting on makeup for the first time ever, that John Hale was actually “tall, dark, and handsome.” I decided he had to be Movie Star Handsome.

Whitney walked by and noticed that I was becoming darker and darker. With his customary dramatic flare and his best stage whisper, he intoned: “Perhaps my memory has failed me. Isn’t this a play about a witch-hunt, which did not happen to take place on the beach.”

The dressing room broke into laughter but it was not at me, it was how Whitney delivered his edict. I had not been shamed. I had just been encouraged to take a second look in the mirror, and become educated as to my “hubris.”

Unquestionably, Whitney Haley‘s favorite student was Greg Fleeman, who could not stop himself from making people laugh. He literally could not help himself. He was constantly funny.

When Greg would bring his chaos to Whitney’s classroom and inadvertently shut down the class, Whitney, with his perfect timing, would stop the class, go into his pocket, and offer him a handful of change: “Greg-or-ee. Would you mind if I interrupted you briefly and trouble you to step out of the room, travel down the hall to the candy machine, and acquire a Milky Way candy bar for me, which I will gladly give you as a reward at the end of this class if you will allow me to continue to pursue my chosen profession?“

Whitney, with his perfect timing, would regain order to his classroom with humor and without injury or shame.

One Christmas vacation, Greg invited me back to visit his family in Miami. His father had been a developer of real estate on Miami Beach, which had made him very wealthy, but Greg, who I believe was his youngest son, had absolutely no interest in taking over his father’s business. Greg’s family had surrendered their son to the Cambridge School Of Weston to let him be who he was, despite their ambitions for him.

The first night I was invited to a somewhat formal evening meal. Mr. Fleeman sat at the head of the table. Greg never stopped talking, and his father never stopped laughing uncontrollably.

Greg went on to become a very original and eccentric rock musician. He also became the apple of his father‘s eye, the family business be damned. Greg was much too eccentric to be appreciated by the audience of his day, but he was invited regularly backstage by those more famous than he.

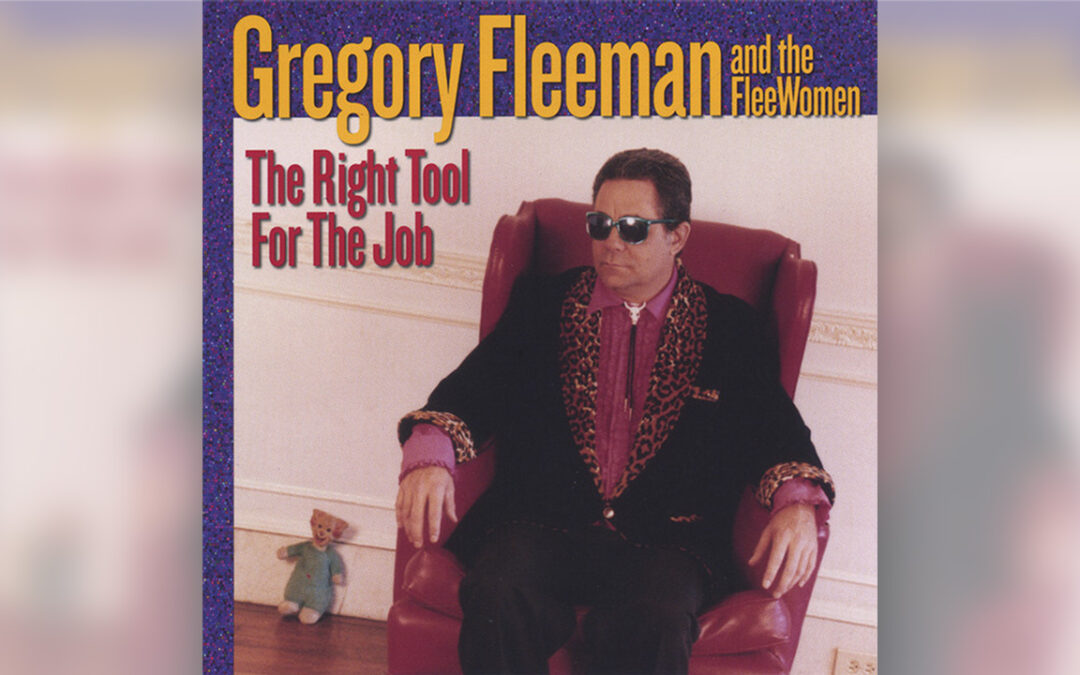

I saw him perform with his band, Greg Fleeman & the FleeWomen, at a small venue in Greenwich Village. He had a small but very loyal following. He was like a standup comedian with an amazing voice. He was always Mr. hubris. but with Whitney whispering in his ear.

Greg Fleeman was far too original to even be considered by schools that granted good grades to those who were able to take notes and recite back what the teachers had said rather than question everything, which is what CSW had taught us to do.

Many of the people who I went to school with describe their experience at the Cambridge School Of Weston as “life-saving.” So it was, not only for Greg Fleeman, but also Whitney Haley and me.

Whitney is long since gone and Greg Fleeman died last year, but he left a CD, “The Right Tool for the Job,” which I go back to again and again, just because it holds all of his irreverence, both in his lyrics and his orchestration. My favorite tracks are “My Ex Wife” and “Skin Tango.”

You can listen to it on YouTube: https://youtu.be/wjqnSOl41Ac.

He was original, and became himself because everybody else was taken.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 15, 2023 | Featured, People, Personal

Back when I was growing up, I was taught two different definitions of success: the so-called “self-made man,” and the person who creates community. For me, two very different people have proved this point.

One was a client of mine in the early years of the law firm I’d created as a sole practitioner in 1990. He was a businessman from rural, hardscrabble Pennsylvania, who had moved to Maryland when he was young and made a lot of money, developing lots for home construction in the Baltimore suburbs. With his success, he built a grand house, lavished gifts upon his wife and three boys and, for himself, he bought a limousine and hired a driver.

The businessman defined himself as a “self-made man.”

The other was my soccer coach at the Cambridge School of Weston, who built a high school sports team at a progressive school in the late 1960s. He was soft-spoken, had an easy smile and natural authority.

Both were entrepreneurial but their styles couldn’t have been more different.

Cambridge School of Weston was a little progressive school outside of Boston. For every other school, the preferred fall sport was football. CSW offered either soccer or rugby, I think because the equipment was cheaper and both of these sports served the character of the school better than football.

Another difference was our mascot. The schools we played against had lions and tigers, bulldogs and bears. We had a gryphon, and our school newspaper was called The Gryphon’s Eye. For half my first year, I didn’t know what a gryphon was. When I looked it up, I found out it was a ”fabulous beast with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion.”

All the other schools had fierce animals, and we had a myth as a mascot, which seemed fitting.

This little progressive school changed my life. It bucked the system and the traditional trends of the times. It taught a Socratic education. It encouraged us to question everything.

Anyway, our soccer coach was typical for this school because he taught us to challenge traditional authority and conventual behavior.

At this time, the strategy of high school soccer was to kick the ball as far as you possibly could down to the other end of the field and then try to score before the other team’s defense would kick the ball back up the field and then try to score using the exact same logic and conventions.

This strategy for the long kick game was dependent on speed and power. It required constant, repeated substitutions of the entire offensive, midfield, and defensive players whenever there was a whistle or break in the action, before the players became exhausted.

Finley was outside of the box from the start. He had to be. We only had about 15 players to fill 11 positions and, to make matters worse, we were ragtag free spirits who sang and played guitar during free periods and attended school in sandals.

Discipline, like running laps, took some reprogramming.

Finley built his future team by turning disadvantage into advantage. He told us that we would not substitute any of our 11 players unless there was an injury serious enough to cause removal. He knew our fear of exercise was real.

He informed us that we would have to get in shape, but he would not run us the way the other teams were trained. He had a plan. He informed us that anyone who kicked a ball that went over the height of the knee of the teammate we were passing to would have to instantly do a lap.

Findley built an offense out triangles. All we had to do is maintain control of the ball by passing, no higher than the knee of the recipient, and that person did the same thing to another teammate to complete the triangle. Once that was established, we were in control of the ball until we could take a shot on the opposing goaltender. If we could perfect this style, we could run the other team ragged, no matter how many substitutions they made.

Basically, it was pinball, but we bonded around it, pretty much mastered it, and my recollection is that we lost only one game against huge high schools, who replaced lines and kicked the ball down the field until we got the ball and again controlled it and scored.

We never were as big or athletic as the other teams. We were in shape, but we never ran like the other teams did. We didn’t have to. Because I was the laziest person on the team, I was the goalie. I think I only was scored on once the entire season not because I was any good but because I never saw the ball.

Findley was admired as a genius but not because he was a self-made man.

The client I represented who saw himself as a self-made man believed the soul of American capitalism was dog-eat-dog. He would, where possible, never pay his bills and, before I represented him, his prior lawyer had set up corporations within corporations that had no assets so that when a lawsuit was filed against him, there would be no money to pay the opponents if they won.

Eventually, no one would do business with him.

He lavished gifts on all of his children because it was important that they loved him, but he refused them a college education because he had none and he did not want them to be superior to him. Two of his three boys became dependent on drugs and were homeless for a period of time.

In contrast, Finley built a team that was a small but cohesive. He forced us to get out of ourselves and into supporting each other and our goal, which was to patiently beat better teams.

I’ve always believed that you are what you do, not what you say. Findley was way ahead of his time in the world of American soccer. The passing game that he taught us had been used before in Europe but he adopted it to fit his needs.

I learned from his wonderful madness.

My client’s wife called me moments after her husband died. He had been waiting for a heart transplant and was receiving daily transfusions to stay alive. When she called me, she was in tears. She said his last words were, “I can’t see! Why can’t I see? I’m not ready to die yet. I’m not ready to die.”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Aug 2, 2023 | Featured, Humor, Law, Personal

I want to tell you about a special award I created and bestowed upon myself.

The Stuffed Shirt Award.

Usually, awards are to celebrate accomplishment — with plaques or statuettes and a large party where such honors are bestowed, like The Oscars and Tonys, or Lifetime Achievement Awards.

However, there are also awards that single out questionable distinction.

For example, the Darwin Awards are annually given for “improving the gene pool.” This is deceptive because it only honors an act so stupid it often ends with the demise of the honoree and is thus given posthumously.

One of the early Darwin Awards went to a gentleman who put a jet rocket engine in the trunk of a Dodge Dart, and died after hitting a vertical cliff wall about 400 feet above the highway.

Somewhere between these two extremes lives the Stuffed Shirt Award.

The Stuffed Shirt Award is typically reserved for professionals, specifically professionals who think too highly of themselves.

The award requires a public demonstration of perceived self-worth, which must be 1) noticed by at least one other person and 2) leads to a moment of genuine disbelief demonstrated by a visible shake of the head by the observer.

An example would be the senior partner at a large law firm I was up against in NYC who FedExed his dry cleaning home to Chicago because he didn’t like the way the dry cleaners in New York City did his shirts.

Hence, the name of the award but the award is not about shirts alone. Here’s how I qualified:

I was fortunate when I first started my law firm back in 1990 to be representing a very large electrical contractor who routinely did huge jobs, such as the electrical work on Coke ovens at Bethlehem Steel, and also the Ted Williams Tunnel, which was towed in 12 sections by tug boats up to Boston from Maryland.

The case covered the construction of a subway system in southern Maryland leading from to Washington DC. There were loads of defendants.

It was an arbitration. The judge and everyone involved had agreed it should be held at the empty yet-to-be-opened subway station where the work had been done. I loved the idea because the subway station “courtroom” was my Exhibit A.

The Maryland State government had many branches and each had different lawyers representing them who were “in-house counsel.” I, however, was an independent lawyer with a big client and I was my own firm and I was damn proud of it.

I had all the makings of a stuffed shirt. All I needed was an event that would lead to a “genuine moment of sincere disbelief and the shake of the head” to be a competitor.

My client and I were seated in the middle of several tables pushed end-to-end, with all the opposing lawyers spread out on the other side.

As the arbitration began, each lawyer introduced their agency. They started at one end of the table, announced the agency, and then announced they were “in-house counsel“ for the agency.

The introductions went from left to right and finally ended after perhaps 15 minutes. None of them were independent counsel. They had all introduced themselves as “in-house counsel.”

Then it was my turn, and I decided that I needed to distinguish myself as an intimidating big shot lawyer.

I paused. I straightened the evidence books and the trial notebooks on the table, leaned forward in my chair, and announced:

“I’m Bob Bowie. Outhouse Counsel.”

My effort at intimidation had fallen short. The laughter rose and renewed several times, echoing in the large empty building. Thereafter, throughout the case, my fellow lawyers would periodically slap me on the back and say how funny I was.

I won the case but had dodged a bullet. There was no plaque or statuette. There wasn’t a celebration. They didn’t even know I had qualified for a Stuffed Shirt Award. To my amazement, this was the start of several long friendships.

Whenever I see them, they are quick to remind me that I am still their favorite “outhouse counsel.”

Self-importance can be like a hot air balloon.

It’s beautiful to see the world from an exulted height but returning back to earth may be its unexpected gift.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jul 25, 2023 | Featured, People, Personal, Travel

Years ago, I met a boy who never once told me the truth but had the heart of a saint.

Back in August 1968, outside of Cheyenne, Wyoming, I was hitchhiking east when a state trooper pulled up next to me. He told me that he was going down the highway for 15 minutes, then turning around, and if I wasn’t gone by the time he came back he was going to lock me up in Cheyenne “until I got a court date.“

This was serious.

As the officer’s taillights disappeared down Interstate 80, I turned around to face the empty road and stuck out my thumb.

I needed a miracle.

As the first car approached, I knelt by the side of the roadway with my hands pressed together simulating prayer.

That car, an old white Ford convertible, was driven by a boy who appeared to be in his mid-20s. He wore a huge cowboy hat, and rhinestones from his shirt collar to his new boots. The boy pulled over and waved for me to get in.

As I thanked him and started to explain my predicament, he laughed and waved off any further conversation. He told me not to worry because he would be driving all night to see his father in Fort Dodge, Iowa.

First car? This guy? It was a miracle… but it gets better.

Next, he asked me if I was hungry. I laughed and nodded yes, and he reached under his seat to hand me a can of peaches, a can opener, and a plastic fork.

He was clearly showing off. You could tell by the grand gestures of his performance and his broad grin. He was having fun.

After I finished the peaches and drained the can of its last sweet syrup, I settled into the ride as he started to talk. He told me that he had been a foreman for the last several years at a ranch, and the night before in Reno, he had girls in the front and back seats of this very car because he had won money in the slots.

As we drove deeper into the night he told me that before he had been a cowboy he had been a soldier of fortune, and had parachuted into Nicaragua as an agent for the CIA.

His stories were endless and detailed, full of life and love and compassion for those he had worked with, and for the women he had been fortunate to love, as well as those who had broken his heart but had been kind enough to have loved him back for a while.

He was a natural storyteller and the more we relaxed together and talked, the more I liked him for his joy.

Slightly before dawn, when we turned off the Interstate and headed up toward Fort Dodge, he offered a surprising apology: “My old man never amounted to much. He was a postal worker. He drank himself out of the job but he’s always been there for me. He is sick now. I never knew my mom. She left him, but my father, he always has been there for me.”

As the light brought color into the outskirts of Fort Dodge, we turned onto a street of freestanding houses in an empty neighborhood with untended lawns, litter on the streets, and an occasional abandoned car.

The door to his father’s house was open and the window next to the front door was broken. As we entered, I looked to the right. There was a kitchen with a table and two chairs. To the left was a living room with no furniture. Straight ahead was a staircase with a simple railing and some of the slats missing, which led to a second floor. There were crushed beer cans on the floor and heaping ashtrays on the countertop by the sink.

The boy headed upstairs to go wake up his father. Moments later, there was some heavy coughing from upstairs and muffled voices. There was the sound of crying, raised voices, but also laughter.

After several minutes, an old man slowly navigated the steps and stopped to catch his breath when he reach the bottom step.

The old man apologized for the state of the house and immediately went the the old ice box. He got three beers and proceeded to handed them out. Apparently, these were breakfast beers.

Oddly, the whole house seemed to be filled with love and I felt welcome.

As the sun came up, the two were lost in each other’s company, and so I timidly asked if I might be allowed to take a shower since I had been on the road for several days. The old man responded “Sure!” He lit a cigarette and pointed at a wash tub leaning against the kitchen wall. He told me to fill it with hot water from the sink and handed me a big jug of dish washing detergent.

I felt that I could not refuse the kindness. I filled the tub with warm water and detergent, stripped naked, and started to take a bath. The boy and his father paid no attention as they laughed and talked and smoked.

Almost immediately the police arrived, knocked on the unlocked door, then entered. They arrested the boy, put him in handcuffs and shoved him through the door toward the squad car out front. The old man burst into tears. With a beer still in hand, he begged them to release his son as the officers pushed the boy down the walkway and put him in the back seat. The officers never spoke to the pleading old man except to say. ”If you touch me, I will take you in too.”

During the entire arrest the police paid no attention to me at all as I sat naked in a wash tub and tried to surround myself with heaps of bubbles.

When the old man returned from the street, he explained through his tears that a week ago his son had finally been released on parole from a Kansas prison. He had been thrown out of school several years before, and had been convicted as an adult for smoking marijuana near the school yard. He wasn’t a bad kid. Just a free spirit from the wrong side of town.

His father had gotten the old convertible for him and told him he could never outlive his past in Kansas. He told him to go west and “disappear” and never come back again.

The boy had initially agreed, but he had told his father upstairs that he had become homesick for the old man and he was afraid he would die and the boy would never see his father again.

Everything the boy had told me for the last 12 hours riding through the night was a lie, and also a life he would never have the chance to live.

The old man said he and his son had talked every week during the boy’s incarceration and the boy had told him he read all the books and magazines and newspapers he could find in prison.

After the old man had fortified his courage with a few more beers, he marched out the front door and headed toward the police station, which was apparently several miles away.

Alone in the empty house, I dried off with paper towels, slept a little on the living room floor, then in mid afternoon, hitchhiked to a postal delivery hub. I got a ride from a man driving a Mail truck headed east toward Chicago. He told me he’d gotten married the day before, and had been up all night. When the driver started to hallucinate dogs running across the Interstate, I volunteered to drive so he could sleep. We switched seats without stopping.

As dawn arrived, with the sleeping driver by my side, I thought about the boy and wondered why he would lie to me all night about a life he never lived, then take me to his home where his lies surely would be revealed.

Maybe it was to show he had a kind heart and a moral code, despite his life. Maybe he just gave up and didn’t care. As the sun was coming up in the cab of that mail truck, I realized that I had never asked his name, nor had he asked me mine.

Years later, it occurred to me that no matter how hard I might try, I would never be able find that boy again.

I still think of him often. He was one of the kindest people I have ever met. He has appeared in my poems and plays as a reminder that we really are what we do, not what we say.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jul 11, 2023 | Featured, Personal, Politics, Travel

Last month I took a trip because I wanted to “feel” what it was like to live in WWII Germany and the Soviet Cold War occupation in Czechoslovakia and Poland.

I already knew the dates, places and times from textbooks, but it’s quite different to experience what it was like to have lived during those times.

Of course the trip would come alive in museums and, unexpectedly, it brought back for me a long lost feeling I had years ago when I was just a young boy. I had gotten lost off shore in Buzzards Bay in a small motorboat that was running out of gas on an outgoing tide in thick predawn fog.

It is odd how we learn through memories and association.

How odd that museums, which were about imprisonment, brought back the feeling of drifting out to sea, creating an odd claustrophobia without barriers other than an endless borderless fog.

The claustrophobia slowly kicked in when I visited Checkpoint Charlie, the famous heavily guarded passthrough in the Berlin Wall, which kept the East Germans imprisoned inside.

It started with a set of pictures of a boy who had scrambled to climb the wall in an effort to live in freedom, but the photos chronicled how he had died riddled with bullets, hanging from barbed razor wire near the top of the wall.

How odd that I could feel claustrophobic under wide-open skies?

A few days later, the claustrophobia increased in one of the East German museums that focused on the Nazi SS and their little gray bread trucks. These had no windows, just a sliding door on one side and three closet-sized cells so small that prisoners could not stand but only sit in a narrow chair, hands by their sides, while they were taken to a concentration camp somewhere outside of Berlin.

A few days later as we traveled toward Prague, we stopped at another prison that was three or four stories high with interrogation cells on the top floor. The inmates who would not answer were showed pictures of their family who would be killed if they continued to resist.

Putin had spent six months in the house across the street when he was in Soviet intelligence, attempting to flip the tortured inmates to become Soviet spies.

The claustrophobia wrapped around me in that silent building when I realized what it must have felt like day and night in there. It was missing the noise of slamming cell doors, the echoing screams and the smell of the single bucket in the corner, which acted as a bathroom in each cramped cell, with three to a single bed and no mattress.

I know now why the feeling I had on this trip was claustrophobic but I thought it was still an odd reaction to the history of the past until I realized I had lived my whole life free in a democracy.

All of a sudden, I felt imprisonment under borderless wide open skies as a psychological imprisonment which became unbearable.

All of a sudden, I could feel the last breath of the boy crucified and bleeding from razor wire on the top of a Berlin Wall as a reaction to my claustrophobia and his death.

Years ago, as I slowly ran out of gas in my little boat, I saw the outline of a cliff as the late morning fog broke. There were connected ladders and a climbing set of stairs. I beached the boat and climbed to the top of the cliff and knocked on the door of a little cottage overlooking the ocean.

A woman with the Sunday newspaper tucked under her arm answered the door. I breathlessly asked, “Where am I?” She looked at me quizzically and answered “Menemsha,” then paused, “Martha’s Vineyard,” and then paused again… “The United States of America.”

I remember feeling happy and alive.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jul 4, 2023 | Featured, Personal, Travel

I have not posted a blog in the last three weeks because I have been to hell and back. I traveled to the darkest place I’ve ever been, and then returned to a place of joy, laughter, love and light.

I went on a trip through World War II in Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, and then returned to witness my son’s wedding and its explosion of joy.

History as dates, places and times is taught and graded, but only the imagination can bring it to life and give it meaning.

In Poland, at the end of our trip, I went to Auschwitz, the concentration camp.

Auschwitz had the most efficient business plan I have ever seen.

I stood at the exact location where the trains emptied, and a guard made an instantaneous decision, pointing either left or right. To the left went children and their mothers (if their mothers could not work) to the gas chambers. To the right went men and women who could be worked to death. The life expectancy of those who could work was pre-calculated to be three months. Excess food was not waisted on them since there was an endless supply of new labor coming off the trains each day. They killed thousands upon thousands of these people each week.

Inside the camp today, there are multiple display cases. Behind the glass of the display cases are piles of clothes, shoes or pots and pans, which had been carried by the executed. In one display case, among the scattered clothing, there was a little pair of red children’s shoes unbuckled. In another, a perfectly intact three-foot-long braid of hair cut from the scalp of a young child. It had a light blue bow still in place at the end.

It seemed impossible to me that the neighborhoods of little country houses outside the camp did not know what was happening in there as the trains rolled in and crematoriums belched smoke that fouled the air. Could they not hear the cries of children as their parents were separated from them or of the families who came to realize that they were not being taken to a safe place outside of Germany as promised, but were living their last moments before they would die.

I was reminded of a time when I was still practicing law, when I was hired to represent a slaughterhouse in a zoning dispute. The slaughterhouse was comprised of two buildings in a suburban neighborhood in Baltimore County.

There was a little house where the business offices were located, and there was a two-story building, which had a ramp that zigzagged up to a door where three cows were lined up head to tail, waiting in line motionless.

The slaughterhouse owners were Christians, and I was introduced to a rabbi who was hired to insure that the process was kosher. I was given the tour of the site in preparation for the trial and I traveled up the ramp that held the three cows and then into the building. I remember doing a double take as I noticed the eyes of the lead cow. I saw that they were wide-eyed and afraid.

Inside the door, I passed the carcasses which had been stripped of their skin and hung swaying on hooks headless as they were carried by a conveyor belt to the efficient butchers, who cut the meat into steaks, fillets, rib roasts, and further down the line, ground beef.

Two days later, I returned from Europe and flew to Houston, where I presided over the rehearsal dinner celebrating my son’s wedding the following day.

The bridesmaids had known each other since high school. Months before, they had celebrated common birthdays together on a weeklong trip to Paris. They were destined to be lifelong friends. My son’s friends had also gone to school or college together and shared comparable deep friendships. The joy and humor of this collective group as they mingled the day before the wedding was palpable and full of laughter and love and friendship on so many levels.

After the wedding ended, the bride and groom traveled into their new life down a runway that was lined on both sides with family and friends holding sparklers.

On the flight home from the wedding, I could not forget the story I was told by our guide at Auschwitz when I asked, “did anyone ever escape?” He replied, “Only the Polish prisoners would occasionally get away because Auschwitz was in a Polish neighborhood where the prisoners could disappear and be exported out of hell by their friends.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 15, 2023 | Featured, Man Machine, Plays

The staged reading of The Grace of God & The Man Machine went very well. It had energy. It came alive.

A staged reading is a collaborative stress test for the words of the story but without the action. Its success or failure for me is measured by the energy generated by the words of the play, delivered by highly talented actors in character without the aid of action on the stage.

A stage play is different. It is an art form, caught between the novel — where the story blooms in the imagination of the reader — and the movie — where the story is told for the screen and, once told, never changes.

The theater performance is the same as the other two in that it is first created by words but it is different because it is delivered to its audience live.

We were blessed with eight characters performed by gifted actors who brought the words alive, so we could see if the play created that energy we were looking for and, in cases where it did not, make the changes needed so they do.

A few nights before Onaje opened at the NYCFringe, I was honored to have dinner with the famous Broadway producer and founder of the Commercial Theatre Institute (CTI), Tom Viertel. I asked him on opening night if he could tell if he had a hit play. He said yes. He told me to sit in the back of the theater where you could see the audience, and then look for any movement — searching for a handkerchief, unwrapping candy, or looking at the program — any motion other than full concentration on the stage. This was evidence of loss of focus, and should be marked in the text.

At ten o’clock, the day of the reading, eight professional and highly successful professional actors met Steve Eich for the first time and they began reading the play together. They had all been provided the script before, but now Steve’s direction was creating a harmony that would create this energy. They broke for lunch at 1:00, and then began their practice performance with editing and interruptions to bring that harmony to the process. I was very impressed by each actor after they finished, and broke for dinner at 5:30 to return, dressed in black for the reading at 7:00.

What happened at seven o’clock was quite remarkable. Each of the actors had become their characters, and I found myself twice lost in the words that I had written, and rediscovered the power of the play exclusively through the interactions of the actors.

At the end of the first act, I was quite surprised and pleased, because there was an extended ovation from what had been a quiet crowd. I had done what Tom Viertel told me to do. I had watched the crowd. They hadn’t moved, and when anyone did move I marked the script.

More importantly, I had felt the energy from the stage and I had been moved by this remarkable collaborative stress test. It worked.

On to the next step.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 12, 2023 | Featured, Man Machine, Plays

It’s TONIGHT, Monday night. Join us! Please use this link to RSVP:

https://robertbowiejr.com/rsvp

Our one-night-only staged reading at Chesapeake Shakespeare Studio Theatre in Baltimore is THIS MONDAY, June 12, at 7:00 pm.

Directed by Stephen Eich, former Managing Director of Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre, and starring a fantastic ensemble of talented actors, this staged reading of The Grace of God and the Man Machine promises to be an exceptional night of live theater you don’t want to miss.

And it’s free!

We’re encouraging theater owners and artistic directors in the Baltimore/DC area to come experience the play, and would love to have you there in the audience.

Chesapeake Shakespeare Studio Theatre

206 E. Redwood St.

Baltimore, MD 20212 (map).

Parking one block away at:

Arrow Parking, 204 E. Lombard St., Baltimore, MD (map).

Doors open at 6:30, performance begins at 7:00.

Please CLICK HERE to RSVP: https://robertbowiejr.com/rsvp

Be there or be square!