by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Jun 14, 2022 | Man Machine, Personal, Plays

I opened the New York Times last week and turned to the theater section and read the headline:

“Dear Evan Hansen’ and ‘Tina’ to End Their Broadway Runs

“The musicals, both of which lost steam after the pandemic shutdown, will close in late summer.”

The article pointed out that before the pandemic Evan Hansen was making $1 million a week in sales but now, because of Covid, successful plays were again falling by the wayside. Tina, about the life and music of Tina Turner also had been doing very well.

Over the last two years, as I watched New York theaters close and reopen and struggle to sell tickets, this kind of news had become the soundtrack of my life. I was used to it by now.

I turned to check my email and noticed an email from Mind the Art Entertainment (MTAE), the producers for my play The Grace of God & the Man Machine, scheduled to open off-Broadway on November 21. It read:

It is with great sadness that I announce that I, as Founder and Resident Artistic Director of Mind The Art Entertainment, have formally submitted a recommendation to our Board to close our company after 15 years.

Producing in NYC is no longer viable for us after so many losses related to the pandemic, including 6 cancelled/closed back to back productions.

This can not be happening!

Almost two years after the remarkable success of a Onaje — my 90-minute one-act at FringeNYC in October of 2018 — after MTAE became its producer, and after several rewrites and three professional table reads lead by dramaturg/ director Kevin R. Free, we had a two-act play with an explosive finish. It ran fast and smooth like a river to a waterfall. We were ready.

Then, after that last table read in March of 2020, the pandemic hit and we all had to wait but we were ready.

In October of 2021, we were surprised and blessed to be offered a virtual trial performance directed by Van Dirk Fisher at the Reliant Theater, who was doing cutting-edge online productions to expansive theater-starved online audiences. It was well received.

We were so ready and this play was perfect for the politics of its time. Its time was now.

Early this year, it appeared that New York theater was opening up, and MTAE booked Theater Row for November to open a week-and-a-half after the midterm elections. That would be perfect.

Now, after almost four years of anticipation and preparation, we have a road-tested redemptive two-act play, rich with true American characters, timed to be performed in November after the midterm elections, but Covid variations were again on the rise.

And just like that, it is over.

The producers sent heartbroken apologies to everyone and have even offered to transfer the off-Broadway lease at Theatre Row free to support a new producer, but it will be next to impossible to mount the play unless a new team is in place by the end of this month.

Yes, I am heartbroken.

But throughout my whole life, I have been blessed by the opportunity provided by crossroads and disasters.

If you are a professional producer for New York theater, or if you know someone who is, just let them know I’m not dead yet and I would be happy to send them the script — but two weeks may not be enough time. (You can click the Contact link in the menu.)

Yes, I know it is almost impossible. But as Hamlet says, “the readiness is all.”

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | May 17, 2022 | Personal, Poetry

I started this blog several years ago in an effort to explore if there could a professional life in the arts after a full and satisfying first career.

Yesterday, I was notified that I had been chosen as a runner up for the Robert Frost Poetry Award for 2022 for my sonnet, “Summer Thunderstorms.” and last month, my sonnet, “City Snow,” was chosen to be included in the upcoming Belt City Anthology: A Lovely Place, A Fighting Place, A Charmer: The Baltimore Anthology.

Both entries are from my book, An Accidental Diary: A Sonnet a Week for a Year.

Help me celebrate and prove that there is the second life, after all!

Please buy a copy of these books and give them away, and ask that they be re-gifted by order of the author.

Here is the Robert Frost Foundation entry:

Summer Thunderstorms

As with the generations long since dead

The fire and brimstone of the status quo

Wakes him up from the safety of his bed

And lightening frames him in the window

And photographs him in its afterglow.

Tonight he feels his present and its past

As the summer storm also comes and goes.

Conclusions are foolish in a world so vast.

For at the edges of his world and heart

Far past the farthest boundary of his grasp

Where ideas cause worlds to come apart

He lives in this place that will not last.

He loves his life more than he can explain

And leaves the window open to hear the rain.

“Week 35” from An Accidental Diary

(Available now on Amazon in paperback and Kindle.)

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | May 3, 2022 | Featured, Personal

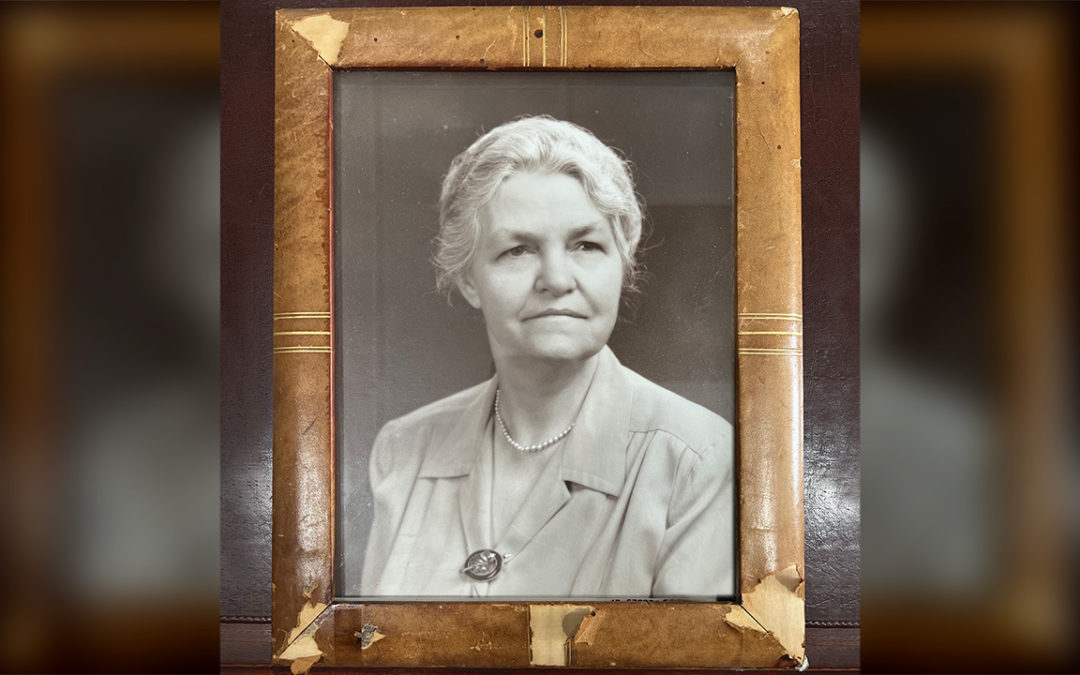

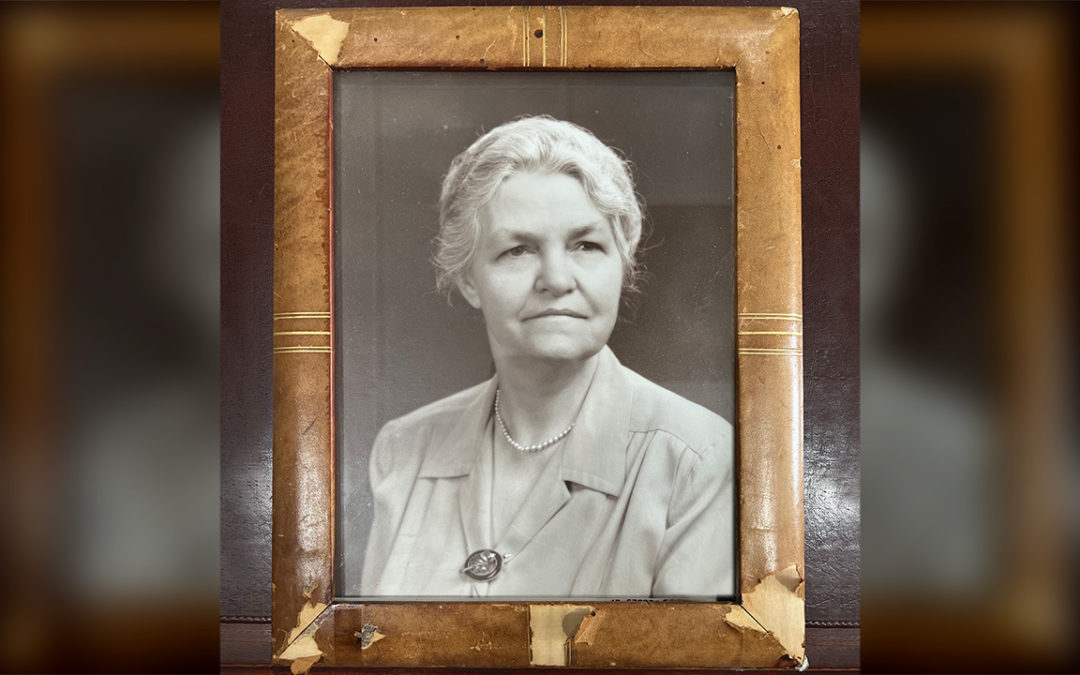

Last week I posted a piece about my mother and how my grandmother would whistle her chickens home long ago on a farm on the eastern shore of Maryland and how my mother, not quite so long ago, used the same whistle to call her children.

My grandmother was the only grandparent I would know. She lost her husband and the farm when my mother was still in high school.

Even though we always lived far apart I remember as a small child feelIng our inexplicable mutual affection when I would wish her happy birthday or Merry Christmas each year over the telephone.

Both my grandmother and my mother had a kindness that children almost Intuitively recognized as safe.

While the schools taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and how to compete in the modern world, my mother and grandmother’s universe was quite the opposite. It was more gentle. They focused on the wellbeing of those they loved. Their world was often damage control.

I was lucky to have known them.

In fourth grade the family moved back to Boston from Washington, and I started my 4th new school in four years. That summer I had developed a temperature of 104 and was taken from Randolph New Hampshire down to Mass General hospital to see Dr. Gross, a specialist in children’s lung problems.

The lower lobe of my left lung was removed which delayed my entrance into a new fourth grade class in which I would already be far behind because of the learning issues that had followed me from Washington.

The following summer I had to meet with tutors every day in order to be bumped up to the fifth grade, I had finally given up on school and slowly started to recess into myself and my gathering emotional despair.

In August, I got a break from the tutoring before fifth grade started.

The next thing I knew, I was scheduled to visit my grandmother in Chestertown, MD for the first time.

My grandmother was in her early 70s and lived alone in one of two small apartments on the 4th floor in an old building next to the bridge over the Chester River, which brought slow moving cars and rattling trucks in and out of Chestertown.

That first evening together, we ate a simple dinner on the card table. Then we went down the fire escape to the backyard with a jar with ice pick holes for air in its tin screw top to catch lightening bugs. Later, when the lights were out, they would be let loose in my room.

Like her daughter, Granny — which is what she wished to be called — had the softest paper-thin skin as she aged but maintained rough dishpan hands, which were perfect for back rubs.

I remember that first night being tucked into bed in an envelope of fitted sheets all alone in the darkness with the lightning bugs.

Somehow my tension disappeared into a quiet world that was my grandmother’s domain.

The next morning she vested me with adult authority. After an early breakfast of griddle cakes with maple syrup, grits, and kettle tea (kid’s tea — milk and sugar but no teabag), it was unspoken but somehow understood that I would be carrying my side of the responsibility by doing the dishes.

At breakfast she planned our day. We would be walking into town to do her errands and I would buy a simple fishing pole, some hooks, a tin pail to hold a small pocket knife, extra lines, some worms, and a red bobber that would flip over and pop up if I got a bite from one of the catfish that the old men routinely pulled out of the Chester River from off the bridge.

Granny had this uncanny ability to create an adventure and treat it like the business of life. She told me not to bother the old men who were fishing but be nice to them if they talked to me.

The men left me alone but they had stopped laughing together and focused on their fishing quietly as they occasionally would look over at me.

As I caught nothing, they caught several big catfish and I was envious. Slowly one of the men came over and asked if I would like some advice. I politely said yes and he pulled in my line, replaced my worm with bait from his pail, put on a sinker, and let the line drop into the brown water until it hit the bottom. Then he reeled it up so that the bobber would react to bites from where the catfish lived.

At the end of the day when everyone left the bridge, I left with them.

Midway through dinner, I proudly announced that I had made a friend. Without looking up, Granny asked, “was I polite?“ I assured her I was, which added to my sense of accomplishment, but I told her I did not catch any fish.

She said that she had done all the shopping that was necessary for our week, so I should be sure if I caught a fish to make sure that I gave it to my new friends. After dinner, and after I had done the dishes, because the sun had not yet gone down, we played slap jack on the folding table and I got pretty good at slapping jacks.

As the sun went down we repeated our collecting of lighting bugs for the room, and the next morning I repeated the day before, but this time with a little more self-confidence. My grandmother told me to leave my windows open so the lightning bugs could rejoin their friends before the next upcoming night.

The men were already on the bridge when I walked up to join them with my pail and fishing rod, and they welcomed me. They clearly had been talking about me after I left them the day before.

I was proud that I had been polite and that they seemed to like me. Within an hour of meeting them, I caught a fish and it was pretty big. They showed me how to remove the hook from the big catfish’s gaping mouth and I dropped it into one of the burlap bags.

The friendships increased into gentle humor, which was respectful on all sides but fun. That night we repeated the night before except my grandmother was laughing when I returned home, because she said that her downstairs neighbor had stopped her on the stairs to let her know that I had slapped a jack so hard the pendulum had come off of the grandfather clock in the apartment below.

I went back to school that fall and continued to fail, but I was less hesitant to call my grandmother just to talk but never to complain. We never talked about anything important but somehow we did.

Later that year, my mother left Boston hurriedly one morning to go down to Chestertown and I grew worried but couldn’t speak.

When I got home from school, my father was waiting.

I told him I was worried about my mother. I wanted to call my grandmother but he took me into the living room and held both my hands in his and said, “you can’t call her now. She has died.“

That was well over 60 years ago. We would both be about the same age now.

Even now, there are still times when I feel that I want to call her but somehow I can’t seem to find the number.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 26, 2022 | Featured, Personal

My mother was a quiet country girl. Even in the suburbs, she used the exact same whistle that her mother used to call the chickens when she wanted us home for dinner.

She married a strict but loving patriarch and had two sons. The three males all believed they were the center of the universe. When she died almost 15 years ago, she left an unexpected void in her place.

The three men she left behind slowly came to recognize she had been our gravity. I don’t think I could have understood her while she was still alive. I think she knew that.

The year she died, she gave me a large steamer trunk, which she told me she had filled with the flotsam and jetsam of my very “learning disabled” childhood. She told me she had saved everything, beginning with kindergarten through when I passed the bar exam and she pronounced I was on my own, “because finally you will never have to take another test again.”

It had been our war, which we fought side by side, against a world eager to write me off, forget me, marginalize me and perhaps us. Because I did not wish to return to that nightmare, I was never ready to open that box.

My mother had no fear of time. She had endless patience.

Because we lived in a patriarchy, we knew all about our family name, with its politicians, governors, distinguished lawyers, and Maryland history. But my mother‘s family of farmers and merchants on the eastern shore of Maryland with its southern roots was rarely discussed.

The year before she died in her mid-90s, she asked me to drive her down to Church Hill, Maryland, where her family of Chapmans, Valiants, and Faithfuls were buried around a small church in an agrarian tidewater town. She said she wanted me to see where she had come from. She had already given me the box by then.

As I recuperated from surgery over the last few weeks, I kept looking at that box. Last Sunday, I opened it.

As I gently pulled back the wrapping paper, I was surprised to find more than I expected. There were pictures of her relatives and ancestors who I had never really known. On the back were the names and dates and a few sentences about who they were and how they connected to my mother and our family. As I put the pictures up on the table and found them staring back at me, her life slowly formed around her in a way that included me.

I noticed that I looked like them more than I looked like my father’s family.

Her father loved poetry and the arts. He had been a choral master and led singing groups and church choirs up and down the eastern shore. There was a beautiful hand-crocheted bed cover, and a white embroidered tablecloth made by her mother, and more pictures of her two older brothers whom I barely knew.

At the very bottom, piled in chronological order and bound by a rubber band that had long since broken, were all of my teachers’ reports. They started with kindergarten reports of a joyous, adventurous, somewhat shy little boy who the teachers found “amazing in his creativity and interest in the world,” until the alphabet and reading and spelling were introduced in first grade and then the failures compounded year after year, as that little boy fell further behind, repeating grades or advancing to the next grade only if he would go to summer school, then encouraged to leave and go to another school, and ultimately to be told he could not go to college.

My mother was patient. My mother had no fear of time. She got me to dictate stories to her as I thrashed on the bed in the vacant third-floor room. She got me to write poems.

Each day after school, she made it her business to read all of my homework assignments to me as we curled up in a window seat, the afternoon sun pouring in through the windows. It didn’t really help, but it was all she could do and she refused to give up on her disappointing son who was always falling behind.

My mother had no fear of time. She had endless patience.

We were all too self-centered to ever recognize who she really was. We all loved her, that was never an issue. But I am now convinced that when she went off to church alone on Sundays, that was something more than her quiet time.

After I spent better than a day with everything spread out on the dining room table, I finally closed the empty trunk. It had been a time bomb to be opened when I could finally understand it. It was an explosion.

Over the years, my father and my brother grew to realize that she had a unique relationship with each of us that was powerful and the source of the gravity that brought us all together. The trunk did not hold the history of my failure as I had thought it did. It held the history of our love as it had matured with faith and quiet determination, year after year, growing strong dispute life’s pressure.

My mother was patient. She had no fear of time.

She waited until I found a voice outside of failure, my family history. She trusted I would find that voice and make it my own. She waited until I found the arts in her family and in me. She waited until last Sunday to be more fully recognized.

There is a poet I love named Philip Larkin (1922-1985). He wrote a quiet poem that stopped me in my tracks when I first read him in college:

The Explosion

by Philip Larkin

On the day of the explosion

Shadows pointed towards the pithead.

In the sun the slagheap slept.

Down the lane came men in pitboots

Coughing oath-edged talk and pipe-smoke,

Shouldering off the freshened silence.

One chased after rabbits; lost them;

Came back with a nest of lark’s eggs;

Showed them; lodged them in the grasses.

So they passed in beards and moleskins

Fathers brothers nicknames laughter

Through the tall gates standing open.

At noon there came a tremor; cows

Stopped chewing for a second; sun

Scarfed as in a heat-haze dimmed.

The dead go on before us, they

Are sitting in God’s house in comfort,

We shall see them face to face–

plain as lettering in the chapels

It was said and for a second

Wives saw men of the explosion

Larger than in life they managed–

Gold as on a coin or walking

Somehow from the sun towards them

One showing the eggs unbroken.

There are times when it takes so long to understand the depth of one’s love you almost lose the chance to say thank you. If I shut my eyes, I can hear my grandmother and my mother calling the chickens home.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Apr 12, 2022 | Featured, Personal

This can’t be real but it’s happening anyway…?

Last week I missed my Tuesday @ 3 posting.

A friend told me, “As you go into the operating room, don’t look at the ceiling because it’s like you’re underneath a giant spider. The legs come down when they do robotic surgery. The doctor isn’t even in the same room.”

This can’t be real but it’s happening anyway?

Then he said “You’ve got to be ready to block it out. Before you go in, give yourself a question to think about and then think about working on solving it all the way through your time in the hospital even through the anesthesia. You will be an unreliable narrator and your answer might make no sense, but you’ve got to be ready to block it all out.”

The operating room doors opened and they pushed my bed to the center of the room. Several nurses were setting up under very bright lights but they had their backs to me. The second hand took baby steps on a wall clock until the minute hand hit exactly 6:45 am.

I didn’t look at the ceiling.

My thoughts turned to my eighth-grade hockey team’s first victory. We were joyously riding back in a school bus in full celebration. The coach was in a separate car and the bus driver had lost all authority on the bus.

There was a ruckus in the back. I turned to see one of the boys secretively drop his pants and moon the late afternoon traffic. I realized that his audience was not the following traffic. It was the boys on the bus.

I was unprepared. I had no question to work on as the anesthesia dripped through tubes into my arm.

Moments later, I blinked into consciousness and I saw my doctor, not the surgeon, saying to me, “you probably won’t remember this, but I came by to let you know they got all of it and it hadn’t spread.”

As I fell back to sleep, l focused on the jukebox in the basement bar I worked in during college. One night, I discovered that from behind the bar I could control the volume of the music and the dimmer for the lights. And that if I made strong drinks, turned down the lights and turned up the music, all that was missing was a high wire act.

Around 2 o’clock the following morning, I woke up and tried to roll over but I was unable to move. I was lost in a tangle of catheters and drainage systems with little bags hanging from a carriage on wheels. I could not move. I had become claustrophobic.

The night nurse reassured me that she also suffers from claustrophobia. She told me it would be good if she helped me out of bed, and I walked up and down the well-lit hall, slowly pushing the carriage holding the dripping bags that flowed into me.

I did laps and more laps, past night nurses who drifted in and out of rooms as they gathered blood pressure statistics and temperatures and returned to their computers like bees to their hive.

I read the patient thank you notes posted on the walls and looked at the list of this month’s birthdays, all in the gentle murmur of motion past midnight.

Everyone left me alone to work out my demons by myself, and I recognized we live in an ever-changing atmosphere our whole life.

Finally, I returned to bed to realize that over the last half an hour while I was walking, my gown had been lifted and snagged to expose my bare bottom to the world and I wondered… is this connected? And then I broke out laughing — fresh beautiful laugher — just because I knew I was alive.

by Robert Bowie, Jr. | Mar 22, 2022 | FringeNYC, General, ONAJE, Operetta, Personal, Plays, Travel

Last Friday afternoon I took the train to New York for the sole purpose of seeing Christian De Gré Cardenas for dinner. The following morning I took the train back home to Baltimore. The only reason for that trip was because he is a friend I just had to see.

It was also a very personal post-Covid-lockdown tip of the hat to celebrate my belief that change is a gift from God.

After my first career as a business trial lawyer I decided I wanted to enter the professional world of theater in New York City, if I could in my late 60s and early 70s.

The only way to get across a chasm so deep was to jump.

Because I was old and no one would read my scripts, I decided I had to take an alternate approach. I decided to use my background as a lawyer so I read all the legal contracts required to be a producer and I took a class in producing theater.

All the young future producers started to ask each other what they wanted to produce. When it came to me I would say: “Nothing. I want you to produce me.”

After I had taken an introductory class at the Commercial Theater Institute in New York, I got a chance to go to the O’Neill Conference in Waterford, Connecticut for an advanced class so I could meet the future big shots.

That trip was a life changer. I hit a gold mine. I met three people within 24 hours who would change my life forever and are my friends to this day: Christian De Gré Cárdenas, Sue Marinello, and Aaron Sanko.

Today I want to talk about Christian and how he has changed my life for the better.

We both got off the northbound train from NYC in Connecticut in the early evening. We were picked up by a van driven by Aaron Sanko, who transferred us to a small motel where we would stay during the conference.

Aaron and Christian knew each other from the New York theater world. I was the old guy in the backseat who didn’t know anything or anybody who had instantly become a groupie.

The next day, Christian and I would be in the same class with Sue Marinello, and we have been bound together with Aaron Sanko ever since. I will talk more about these, my collaborators and friends, as we approach the opening of Mind The Art Entertainment’s (MTAE) upcoming performances, which will be premiering in April, July, and November in New York.

When Christian and I got off the train we looked like two Willy Lomans walking on stage in Death of a Salesman. After we were delivered to the motel and were waiting to register, I decided to talk to Christian and asked him if he would like to go get a drink after we checked in. He never got a chance to answer because the night clerk interrupted to tell us: “Forget about it. Everything is closed.”

Sue Marinello and I sat next to each other at the conference, and she committed to reading my play Onaje. Shortly thereafter, Christian suggested we apply to the upcoming New York Fringe Festival.

After the remarkable success of Onaje, Christian offered me a chance to write Vox Populi, his final operetta in a series based on the seven deadly sins. I immediately accepted and we agreed to meet at a restaurant in Spanish Harlem next to his apartment, where we would sketch out the plot and talk about the tone and temperature of this comedic operetta.

We had the restaurant to ourselves and the waiters brought us food and mescal throughout the afternoon, until the restaurant was set up for the dinner crowd to come in. It was magic.

I went back to Baltimore and went to work at a feverish pace and completed a rhyming rollicking first draft that Christian liked. He invited me to go to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, to marry the music to the words.

Each morning we would get up and go to a little breakfast place that had a wide open garden with a little pond, a beautiful flowered fence, and a balcony with tables for breakfast. We were often alone as we started our day of work.

During breakfast we would go page by page editing the draft, and in the afternoon Christian went to work writing the music while I made changes to the script. Later in the afternoon, Christian would play back the music he had created. In the evening we went to magnificent restaurants in San Miguel and drank more mescal.

Around the plaza and the magnificent church, mariachi bands would sing for the locals, as well as the tourists, and we would walk the streets and listen for music coming from the rooftops. When Christian liked the sound overhead we would enter, go up the stairs, order another drink, and listen until we moved on to the next venue. It was magic.

When we got home at night Christian would go back to work, and in the morning, before we went to breakfast, he would play back what he had composed the night before.

This routine went on for well over a week and somewhere during that time we became brothers in creativity and laughter, and deep friends.

It is amazing how we all step in and out of unique worlds as we change careers or grow older. In my case, as my second career evolved and as I grew older, I stepped into an amazing world of people and experiences that have made me richer and more fortunate.

Unlike any profession I know of, the theater welcomes humanity into an opportunity for friendship in a way somehow the world cannot achieve.

During our dinner in New York last Friday, we were talking about something but I can’t remember what. I just remember Christian looking up straight into my eyes in a moment of surprise and saying: “Do you realize I am exactly half your age?”